Speaking of music as an activity, as a verb, a ‘musicking’, music scholar Christopher Small contends that “the act of musicking establishes in the place where it is happening a set of relationships, and it is in those relationships that the meaning of the act lies” (Small 1998: 13). This theory is valuable for highlighting the historically and culturally contingent nature of musical acts, and lends specific insight in considering the genre of the lullaby. Lullabies, simultaneously “sleep songs” and “work songs” (Davis 2021: 63), embody and express significant relational connections, forging meanings between adult care-givers and infant care-receivers through interconnected and interdependent acts of musicking. Paradigmatically, lullabies take place within the constraints of domestic spaces and the unique conditions of nocturnal time, with at least two participants taking part: generally, one adult – more often than not, a woman – and one child. Musical vocalizations; physical motions; ambient noises; and verbal, non-verbal, and pre-verbal utterances all take part in the aural musicking of lullabies. We may imagine the enormous variations involved in these acts: the adult singer’s vocal quality, musical training, and level of exhaustion; the lyrics that express words of tenderness and joy, heartbreak and wrath, incantations against dangers, or memories of ancestors; and the participation of the child, whether somnolent and compliant or restive and full-throated. Regardless of these factors, a large majority of lullabies can be musically characterized by their overall soft dynamic level, gently rocking rhythms, and prosodic character redolent of what researchers term ‘Motherese’, “a sing-song, exaggerated vocal style adopted by mothers of neonates in all cultures” (Davies 2011: 383).1 Taken together, the place, participants, and performance of lullabies offer a rich context for the establishment of important, if not complicated, human relationships between adults and children.

These associations and generic factors continue to play a central part in the meaning-making of lullabies even when they are recontextualized in different musical and social environments. During the nineteenth-century, lullabies reverberated in semi-private salons and concert halls, tenderly sung as solo art songs with piano accompaniment, as operatic arias, or as compositions for mixed-voice choirs.2 Composers also created wordless lullabies that translated the vocal qualities of Motherese into instrumental idioms such as the rhapsodic virtuosity of piano and string compositions, sometimes with the dramatic support of full orchestras.3 These acts of musicking significantly altered aspects of lullabies, even as they made use of its shared meanings and generic characteristics. Actual children were conspicuously absent from participating in these lullabies, which in general took place within decidedly adult-dominated and often male-oriented contexts in terms of performers, composers, critics, and audience members. The soporific effect of the music now served a largely metaphorical or narrative function, eliciting Romantic imagery of the idealized mother-child dyad. As Marina Warner writes, “It is the Romantic cradle song, with its rocking rhythm, its sentimental icon of mother and baby intimacy, and its sweet untroubled domesticity that on the whole dominates perception of the lullaby” (Warner 1998: 196). This sentimentalization and recontextualization largely served as a means by which adults participated in shared expressions of the sacralization of domesticity, the establishment of national identity, the consideration of folkloric antiquarianism, and the poetic contemplation of existence.

In this study I consider a further recontextualization of lullabies as themes in imaginative children’s music for piano.4 Concurrent with the collection and marketing of lullabies as part of a burgeoning market in “children’s literature” (Davis, 2021: 76), this domestic genre returned lullabies to the home and to the participation of children, but altered the nature of that participation while reinforcing the ideology of sentimental Romantic childhood. Domestic spaces held deep ideological importance as sites of middle-class identity formation, in which rituals such as private music making played an important role. Adults participated mainly as both informal and formal teachers, and as the composers of published works, the latter an overwhelmingly male-dominated category, and children engaged with these expressions of adult authority through the physical presence of teachers as well as via the adult-mandated rules of musical literacy and correctness. These instrumental lullabies were no longer “sleep songs” in any literal sense, but decidedly “work songs” that required young children to develop musical skills, practice emotional sensitivity, and internalize appropriate social roles and norms.

Utilizing Maria Nikolajeva’s theory of aetonormativity, I argue that lullabies in this context function as expressions of adult hegemony over children, operating as a covert mechanism of socialization that held significant ramifications for the negotiation of gender and age boundaries. I begin by contextualizing this form of musicking, underscoring the social significance of domestic piano practice and performance, and explaining the ways in which imaginative children’s music thrived in this social niche and reflected social imagery through its multimodal characteristics. Although boys undoubtedly participated in piano playing, I focus on the impact of this musicalized socialization on girls, a perspective justified by the feminine gendering of private piano performance and the preponderance of young, female players during the long nineteenth century (Parakilas 2002: 121). Seen in this way, lullabies contributed to the establishment and maintenance of social ideologies on childhood, girlhood, and motherhood. I analyze select compositions and consider the ways in which musical characteristics, textual descriptors, and visual illustrations combine to vividly communicate these social narratives and expectations. My selection does not prioritize works by canonical composers or famous works; rather I have chosen to emphasize the pervasiveness, longevity, and stability of these remarkably homogenous lullaby conventions for children by drawing examples from composers across the western world – France, Germany, Russia, and the United States – between the second half of the century to 1920. I organize my analyses based on the music’s depiction of model social relationships in which young pianists practiced feminine self-regulation, the positioning of the ‘good mother’ in relation to children and the home, and correct maternal behavior through a conflation of doll play and piano play. In the final section, I offer counterexamples of lullabies written by two female composers, arguing that they offer more empowered and fully human images within this tradition.

1. Socialization in Instrumental Lullabies

Lullabies in imaginative children’s music were made by adults for children, and as such, they reify the adult’s culturally contingent and ideologically laden conceptualizations of childhood, presenting actual children with both descriptive and prescriptive models of identity. Maria Nikolajeva developed the concept of ‘aetonormativity’ to theorize this power imbalance in children’s literature, arguing that because adults establish social norms, the adult definition of normativity and alterity “governs the way children’s literature has been patterned from its emergence until the present day” (Nikolajeva 2009: 16). She continues,

The child/adult power imbalance is most tangibly manifested in the relationship between the ostensibly adult narrative voice and the child focalizing character. In other words, the way the adult narrator narrates the child reveals the degree of alterity – yet degree only, since alterity is by definition inevitable in writing for children. Indeed, nowhere else are power structures as visible as in children’s literature, the refined instrument used for centuries to educate, socialize and oppress a particular social group. (Nikolajeva 2009: 16)

What she says of children’s literature is equally valid for children’s music. Adults hierarchically confront and manage the alterity of children when they establish the criteria for children’s musicking, in which the musical and the social intertwine. As Katherine Bergeron states, at the piano, students attuned themselves to a system of ordered values, learning to reproduce those values according to the laws of the discipline. This type of social control insists that “to play in tune, to uphold the canon, is ultimately to interiorize those values that would maintain, so to speak, social ‘harmony’. Practice makes the scale – and evidently all of its players – perfect” (Bergeron 1992: 2-3). Aetonormativity proves a potent tool for exploring the socializing pressures of imaginative children’s music, by critically considering the ways in which adults frame children through the musicking of domestic piano practice, as well as the ways in which children are represented through music, text, and image.

The ability to own and play upon a keyboard instrument in the home had acted as a marker of social largesse, musical literacy, and feminine propriety since the eighteenth century. This was particularly true for young girls in the growing middle-classes for whom the highly gender-specific activity of piano playing functioned as the ideal instrument for them to hone and display chaste and virtuous behavior. These so-called ‘feminine accomplishments’ participated in the symbolic enactment of cultural boundaries that played across socio-economic, racial, gender, and age lines. The ‘labor’ of piano playing by middle-class, white girls differentiated them from the peasantry, urban poor, and minorities – whose physical labors were the results of economic necessity and compulsion – as well as from the nobility – whose labors were perceived as power-hungry, lascivious, and extravagant (Loesser 1954: 64). It also differed from the labors of business and commerce undertaken by adult men in the morally-questionable public sphere. Rather, young women were expected to perform their status in the comfort and safety of drawing rooms where they “played the piano in a gentle, sweet, and correct manner”, utilizing the preponderance of method books, exercises, and sheet music deemed socially appropriate for such musicking (Byrd 2020: 441).

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the tradition of repetitive and mechanistic études were emblematic of the musical education of children (Deahl 2001: 28; Parakilas 2002: 115-119). However, with the emergence of imaginative children’s music during the 1840s, they were provided with programmatic pieces specifically designed to encourage their innate creativity and sensitivity (Kok 2010: 269-270).5 Robert Schumann (1810-1853) was a key figure in this development, with his Kinderszenen [Children’s scenes] op. 15 (1838) and Album für die Jugend [Album for the young] op. 68 (1848) establishing important generic parameters for imaginative children’s music worldwide.6 Schumann espoused a holistic conception of music education for children, repeatedly denigrating what he saw as the wastefulness and mindlessness of tedious exercises and pedantic theory. As early as 1834 he insisted that such music was nothing more than “the faithful yet lifeless mirror that reflects truth silently, remaining dead, without an object to animate it” (Schumann 1834: 75).7 Contrarily, he employed programmatic techniques to imbue his educational music for children with the inspiring spark of fantasy, characterizing his collection Album für die Jugend as a compendium of “forward-facing mirrors, premonitions, prospective states for the young”.8 In contrast to the “lifeless mirror” of études and theory, the “forward-facing mirrors” of imaginative children’s music focalized children as artistic subjects as well as active performers. Musicalized images of childhood offered actual children models of behavior and allowed them to mature musically, emotionally, socially, and spiritually. Composers and publishers throughout the nineteenth century strategically developed a lexicon of child-appropriate themes to populate musical worlds that reflected domestic, fantastic, natural, and emotional scenes back upon young pianists (Kok 2008: 100; Eicker 1995: 53-56). Lullabies proved particularly popular within this context. Their simple and straightforward musical features – characterized by formal clarity (AA or ABA), synchronized combinations of tuneful melody (in the right hand) and rocking accompaniment (in the left hand), and overarching use of quiet dynamics – made them ideal pedagogical repertoire for beginning players. Additionally, the programmatic image of the lullaby with its associations with the musicking of mothers and children was considered both suitable for and relevant to the young. This image was largely expunged of its real-world complexities, frustrations, and anxieties, instead depicting a sentimentalized ideal that emphasized domestic peace and intimacy. This framing of the lullaby delineated a highly selective ‘forward-looking mirror’ for children, one that expressed the aetonormative and patriarchal values in which they were musicked.

For young, female pianists, the musicking of such lullabies engaged them in lessons of socialization that reiterated and reinforced two ideologies that were vitally important to nineteenth-century society: girlhood9 and motherhood.10 Carol Dyhouse connects the concept of adolescence to the nineteenth-century, stating that “as industrial society came to subject children and the young to ever longer periods of tutelage and formal schooling, the transition from childhood to a generally recognised [sic] adult status became more drawn out and complex” (Dyhouse 1981: 115). As a result, the myth of adolescent girlhood as a distinct cultural category received increased attention throughout the course of the century in artistic and public discourses. Beth Rodgers points out that girlhood represented a “difficult to define, ‘melting’ stage of life between childhood and womanhood”, an ambivalent and polysemous category that prompted and justified aetonormative responses in the form of adult guidance, encouragement, and warnings (Rodgers 2016: 1). In her analysis of the ubiquitousness of the so called “piano girls” of the nineteenth century, Ruth Solie borrows the concept of “girling” from feminist philosopher Judith Butler, a term which describes “a two-way process that marks girls’ lived experience of their culture’s values”. She continues, “On the one hand, girling is the social process that forms girls appropriate to the needs of the society they live in; on the other, it is their own enactment – or, in Butlerian terms, their performance – of girlhood” (Solie 2004: 86). Girling and musicking go hand in hand.

As Ivan Raykaff puts it: “A piano girl was supposed to become a piano woman, satisfied by marriage, motherhood, and the musical pursuits of proper domestic life in the patriarchal social order” (Raykaff 2014: 184). The amorphous boundary land of girlhood successfully traversed, women were expected to enter into the stability of a middle-class womanhood characterized by conjugal monogamy, maternal care, and home comforts. During the nineteenth century, motherhood was venerated as the ideal adult female identity, and served an important function in supporting the culture of domesticity. Mothers acted as the moral center of their households and held great responsibility for symbolically tending the symbolic sacred hearth of the home, ensuring its function as a peaceful respite for her husband and a sanctuary for the protection and proper development of her children. Success in this endeavor required women to aspire to idealized standards, acting the part of “The Angel in the House”, the embodiment of gentleness, love, purity, piety, submissiveness, and selflessness.11 Childcare – which in the pre-Industrial Revolution era was often divided between mothers and fathers, as well as outsourced to extended family members, community members, and wet nurses (Thurer 1994: 166-167) – became the exclusive purview of mothers, who, it was argued, were naturally predisposed to the task (Thurer 1994: 210-211).12 The ‘good mother’ always placed the needs of her children above her own, finding her life’s fulfillment in the sacred calling of her domestic duties. But as Sheri Thurer states, “by the Victorian era, the veneration of mothers had become a thinly veiled guise for their exploitation” (Thurer 1994: 205). The exalted status of “The Angel in the House” served to subjugate actual mothers by requiring them to live up to ultimately impossible standards of behavior, to gratefully find complete fulfillment in the unpaid marginality of the domestic sphere, and to shoulder alone the ever-increasing burden of child-rearing. The untroubled and idealized nature of instrumental lullabies avoided such social complexities, instead habituating young pianists to dominant social myths in which their roles as children, girls, and mothers required, above all, self-regulation.

2. Lullabies as Self-Regulation

The hammer mechanism of a piano made possible a wide spectrum of dynamic levels with the struck strings responding to the gentle and forceful pressure of a player’s fingers with soft and loud sounds. This direct correlation between instrument and performer made the piano an optimum vehicle for musical expressivity, making audible the player’s emotions. However, this also allowed the piano to function as a means of emotional socialization in that adults could quickly perceive timidity or violence in a child’s playing and administer correctives. In the case of instrumental lullabies, the correct execution of quiet dynamics acted as a form of musical supervision. Furthermore, as a ‘forward-looking mirrors’ depicting idealized scenes of motherhood, the lullaby’s quiet dynamics simultaneously trained young girls in gentleness, selflessness, and self-restraint. No matter how much one might feel like ‘thumping’ the piano, one mustn’t wake the baby! French composer Renaud de Vilbac (1829-1884) offers a useful example in “Sommeil d’Enfant: Berceuse” [Child’s Sleep: Berceuse], the tenth piece from his publication Échos de Jeunesse [Echoes of Youth] (1879). A short introduction begins the piece, “Andantino” with a 6/8 time signature in F major, with short, upward-arching motives interrupted by a series of lone Cs – possibly indicative of a chiming clock signaling bedtime. Beginning with a piano dynamic level, the volume swells only momentarily, returning to piano for the A section, which features a simple melody marked “very much singable” [ben cantabile] over a rocking accompaniment. The B section follows, using material from the introduction and requiring the performer to swell the dynamics every measure. This heightening of the modest emotional expression of the piece leads to a climax where a brief shower of graceful sixteenth-notes crescendo in the upper register before diminishing and slowing to the silence of a fermata. Vilbac then begins anew with the opening A section melody, varying the repetition slightly with sixteenth-notes now energizing the B section into another climax. The piece concludes with a final A section, this time marked “a little more slowly” [un poco più lento] and “as gently as possible” [dolcissimo] before slowing to “Lento” and fading away into the delicacy of a ‘“pianississimo” plagal cadence. This lullaby hinges upon the dichotomy between tranquility and virtuosity, musically and symbolically emphasizing the reigning in of emotional outbursts and musical superfluity. Although many girls achieved high levels of technical skills at the piano, the vast majority could not attain notoriety in the public sphere, a destiny open primarily to men (Parakilas 2002: 119); rather, girls were expected to frame their musicking as “strictly non-public and therefore un-virtuosic” (Cvejić 2016: 219), relegating themselves to a self-regulated, domestic future as selfless, lullaby-humming mothers.

Figure 1. Illustration by Charles Henri Pille for “Berceuse” in Vingt pièces enfantines by Francis Thomé

The use of illustrations provided imaginary children’s music with additional visual interest and invested them with a more vivid mirror of prospective social states. Each piece of Vingt pièces enfantines [Twenty children’s pieces] op. 58 (ca. 1883) by French composer Francis Thomé (1850-1909) are headed with half-page pen illustrations by renown French artist Charles Henri Pille (1844-1897) “Berceuse” [Lullaby], the seventh piece in the collection, features a depiction of a grown woman in a voluminous dress sitting in a chair beside a large, wooden bassinet with a half cover. (See Figure 1). A somnolent baby, lips parted and eyes closed, lays within the cradle, their head propped slightly by a large white pillow and a blanket tucked snuggly around their torso. Looking down at the child, the woman’s right hand grasps the side of the bassinet and her mouth is slightly open, suggesting that she is in the midst of both rocking and singing. This visual depiction of correct maternal care is reflected and augmented in the music, which emphasizes quiet dynamics; a rhythmically simple melody marked “very well sung” [ben cantato], and an accompanying tapestry of descending arpeggios with the indication “as sweetly as possible and sustained” [dolcissimo e sostenuto]. Though the piece is not without its tensions – featuring affective, chromatic harmonic progressions and five indications to hold back the tempo – the performer must maintain decorum through predominantly quiet dynamics, fading away at the close into a “pianississimo” haze which brings this demure recital of future motherhood to a close.13

When composers and publishers included references to the lyrics of known lullabies either as titles, subtitles, or epigraphs, they further connected instrumental lullabies to the realities and myths of gendered domesticity. For young, female pianists, the interplay between poetry and music may very well have placed them even more ambiguously between two uneasy identities. On the one hand, the lyrics imbued wordless melodies with verbal signification, allowing girls to evoke the maternal voice and play the part of adult care-giver. But on the other hand, the aetonormative, child-directed words of many lullabies were far from tender. Marina Warner states that “threats are interwoven into the games and songs and stories of the nursery itself” (Warner 1998: 33), and lullabies often offered adults outlets for taboo feelings. In Aus der Kinderwelt [From the child’s world] op. 74 (ca. 1886) by German composer Cornelius Gurlitt (1820-1901), “Schlummerliedchen” [Little lullaby], the collection’s fifth piece, includes two lines of poetry beneath the title: “Go to sleep, my dear child, / For the wind sings outside!”.14 These lines would have been widely recognized in German-speaking lands as the opening to “Im Winter” [In Winter], a Christmas-themed lullaby-poem by German poet Robert Reinick (1805-1852).15 In the complete poem, four stanzas express the sentiments of an adult care-giver addressing a restless child with the imagery of anthropomorphized nature. The first two stanzas are translated below:

Go to sleep, my dear child,

For the wind sings outside.

It sings the whole world to rest,

Covers the white beds.

And it blows in the world’s face,

Which does not move or stir,

Does not reach one little hand

Out from its white cover.

Go to sleep, my sweet child,

For the wind paces outside.

It taps on the window and looks inside,

And hears a child crying,

Then it scolds and hums and growls mightily,

Straightaway fetches its bed of snow

And piles it on the cradles,

If the children will not lie still.16

The poetry intertwines the child’s behavior with that of the wind, which acts as a natural and powerful corrective to disobedience, praising the stillness and sleep of the frozen earth, and threatening to punish the child’s restlessness with an avalanche of snow. The wind acts the part of a stereotypical nursery bogey, allowing adults to obliquely express their frustration and conflicted feelings. As Maria Tatar writes, infants to whom lullabies like this were sung undoubtedly had no conscious understanding of the word’s menace; “how older siblings or any other children within earshot react to the words is less easy to calculate, though one can only speculate on a range of responses from gleeful satisfaction to nervous anxiety” (Tatar 1992: 34). It can be assumed that many young pianists could clearly understand the threatening messages of the poem, and for them their actions as pianist has them simultaneously expressing the nurturing mother, the disobedient child, and the menacing wind. Gurlitt’s music offers a subtle musicalization of this tension. Marked “Sanft wiegend” [Gently rocking], the piece utilizes two themes arranged in an AABABA form. The A sections betray tension, both harmonically, through the use of fully-diminished seventh chords, and rhythmically, through melodic syncopations, a musical antagonism that could speak to the agitation of the child or the howling of the wind, which itself stands in for the frustration of the adult. The dynamics throughout are marked piano, aside from a short crescendo that leads from each B section back into the quiet distress of the A sections. Contrarily, the B sections intone a more rhythmically regular melody set lower in the alto range, possibly representative of the voice of the “Angel of the House”, that fictional and selfless mother who finds complete satisfaction in care-giving. It is also in the B sections that the accompaniment widens considerably and requires the pianist’s left hand to traverse three octaves in as many measures, a somewhat challenging task for small hands, especially when attempting to maintain the piece’s gently rocking character. This music offers young girls the opportunity to confront complex social identities, musically enacting the laws of aetonormativity and feminine self-regulation on the road to motherhood.

3. Mother Adjacent

In some instances, the performance of both girlhood and motherhood were made implicit in the musicking of an instrumental lullaby through the physical presence of the mother as instructor and duet partner. Solie points out that

women’s prescribed role as providers of music – and other emotional – sustenance for family and community entailed as well their responsibility to teach the skill to the next generation. The vast iconography of women at keyboards contains a substantial subset of pictures of this intergenerational transaction (Solie 2004: 100).

In the sixth edition (1870) of the pedagogical treatise L’enfant pianiste [The child pianist] by Russian pianist Matvei Ivanovich Bernard (1794-1871) he guarantees that by studiously practicing his collection of dances, airs, and operatic excerpts, children as young as six would attain a strong familiarization with the piano in as little as two years. Bernard maintains that all this progress ought to take place under the guidance and nurturance of the child pupils’ own mothers. In the inner title page an elaborate dedication in Russian, French, and German reads: “Collection of little, easy pieces for piano written for the purpose of igniting the love of music in children, and dedicated to good mothers who desire to teach their children the principles of music themselves, by M. Bernard” (Bernard 1870: Preface Section, emphasis mine).17

Figure 2. Illustration by unknown artist for L’enfant pianiste by Matvei Ivanovich Bernard

These words surround an illustration of a boy and a girl in a curtained-draped playroom, the boy seated at an upright piano with L’enfant pianiste resting on the music rack and the girl standing to the side holding a doll, a significant framing of gender roles that, in the case of the girl, intermingles her musical and social educations. (See Figure 2). The mother, Bernard’s co-teacher, is conspicuously absent from this illustration, yet her participation is vital to the success of the child’s musical education. In a self-flattering preface Bernard directly enjoins mothers, “let playing the piano be a pleasure for the child, not a dry, scholastic exercise” (Bernard 1870: Preface Section).18 There is an implication here that musical instruction should also be a pleasure for the mother, a form of emotional compensation as she is exempt from monetary remuneration.

Bernard begins the musical journey of mother and pupil with simple fare, such as the second piece, “Баюшки Баю19 / Berceuse” [Lullaby], an eight-measure-long lullaby in miniature, indeed, a lullaby in its infancy. The piece consists of a simple four-measure melody that is repeated verbatim, while the left hand provides a rocking, drone-like accompaniment. Nevertheless, a six-year-old unaccustomed to the placement of the hands on the keyboard, the meaning of the lines and spaces of the treble clef, or the rhythmic values of half notes, quarter notes, and eighth notes would undoubtedly require instruction. Rather than guiding a child to sleep with a lullaby, here the ‘good mother’ plays a tacet part in Bernard’s pedagogical project through guiding her child through the rudiments of sheet music notation. This posits a system of social relationships in which the mother enacts her own maternal goodness through free and grateful musical labor, a lesson in gender norms and expectations as meaningful for a young girl as any piano instruction.

In addition to pieces for solo piano, imaginative children’s music included four-hand duets in which two players sit side by side – “Primo” on the right and “Secondo" on the left – and play the same piece together.20 Musicking in this manner with such close proximity between the participating performers “expressed close familial unity”, writes Adrian Daub, and intensifies the possibility for relationship formation and socialization (Daub 2014: 35).21 This is particularly true in the case of young, female pianists playing alongside their own mothers, an intimate activity in which a child and an adult sat on the same bench, read from the same book, and touched the same keyboard. Musically this configuration reifies the alterity of childhood and socially acceptable practices of assimilation and socialization by which that alterity be properly channeled. The composition Le Maître et l’Élève [The master and the student], op. 96 (1920) by Polish-Jewish born German composer Moritz Moszkowski (1854-1925) contains eight duets, and draws a sharp distinction between the skill levels of the performers. The master’s “Primo” part requires substantial technical skills to execute large chords, contrapuntal and rhythmic complexities, wide leaps and runs, as well as operating the sustain pedal, while the student’s “Secondo” part is restricted to five adjacent notes per hand, often written in parallel octaves. This pianistic disproportion underscores the aetonormative difference between children and adults, creating musical situations in which the child’s part barely registers at a sonic level, buried beneath the dazzling display of the adult’s. The performance of an instrumental lullaby in this context adds a further layer of significance in which potential mother and daughter duos practice feminine self-regulation side by side, providing a musicalized commentary upon domestic expectations and familial roles. In the sixth piece of this collection, “Berceuse” [Lullaby] the “Secondo” part is supremely simple, consisting entirely of a slowly moving bass line played by the right hand alone for the first two-thirds of the piece (sections A and B). At the return of the opening material (section A’) the left hand joins, doubling the right at the octave. Minimal, placid, somnolent, this music has an innocent and artless quality, visually empty due to the abundance of rests, white half notes, and black quarter notes, and musically fragile as the strike of long-held notes fade away in the moderately slow “Andante” tempo. Whether or not this music would have been challenging or simplistic for young girls,22 symbolically the “Secondo” part appears analogous to the idealized image of a sleeping baby, and it is from this vantage point that she would have been able to observe a musicalization of maternal duty and nurturance. The upper register of the keyboard is dominated by the mother’s “Primo” part, which contains significant challenges including a legato melody, contrapuntal countermelodies, passages of parallel thirds, chromatic harmonies, and syncopated arpeggios. From the first measure to the last there is hardly a moment when the mother’s “Primo” part does not demand assiduous work as she produces a nearly continuous stream of visually and aurally busy sixteenth notes, each requiring careful phrasing and pedaling. After an initial theme in D major (section A), the mother’s music shifts to B minor (section B) with a series of descending melodic fragments, returning to the opening material (section A’) now with full and large chords in both hands joined by more streams of sixteenth-note filigree. The mother’s music dominates the daughter’s, even as it cradles it in a flurry of musical activity. Additionally, aside from two brief crescendos, Moszkowski requires that both players practice self-regulation and maintain a piano dynamic level. This task requires much more on the mother’s part; her musical labor must be both intricate and quiet, graceful and unpretentious. This is particularly evident in the approach of the A’ section where Moszkowski indicates a decrescendo, avoiding and subverting any extroverted display of expressivity in favor of a molto piano rendition of the opening theme now enriched with fuller chords. Interpreted as a musicalized display of prospective motherhood, this coordinated quieting of the lullaby’s dynamic possibilities offers girl pianists a demonstration of the skill required to perform motherhood.

4. Putting Down Dolly

Another widespread convention of imaginative children’s music included instrumental lullabies that made references to doll and doll play.23 If children gain aetonormative knowledge through observing the modeled behaviors of adults, then the activity of playing with dolls demonstrates the child’s internalization of those social lessons and reveals the “reproduction of power” (Nikolajeva 2009: 22). While children have interacted with dolls from time immemorial, the nineteenth century witnessed the production and consumption of dolls in a new way. According with the advent of the concept of the “maternal instinct” at the end of the century (Tanaka 2019: 30), adults considered dolls socially useful in the performance of girlhood and the rehearsal of adult womanhood. Girls were expected to nurture their dolls by such rituals as “dressing and undressing, feeding, bathing, and putting their dolls to bed” (Formanek-Brunell 1998: 184 Yet often adult expectations were resisted by children who treated their dolls roughly through verbal and physical abuse, and dispatched them in order to act out doll funerals (Formanek-Brunell 1998: 20-23). It was not enough that children had dolls, but that they understood how to play with them in ways that mirrored socially accepted conventions of feminine care-taking. Doll lullabies equated correct piano playing with correct doll playing. This holds true for “Puppenwiegenlied” [Doll Lullaby], the third piece from Gurlitt’s Aus der Kinderwelt, which dilutes the lullaby to its most basic, possibly most ‘child-like’ elements. Marked Wiegend [Rocking], the piece outlines simple harmonies in steady, left-hand arpeggios while the right plays an undemanding melody within a narrow range.24 Gurlitt goes out of his way to eschew musical complications or tension, repeating the simple melody an up an octave with slight ornamentation in the second half of the piece and maintaining quietude throughout.

The musical, textual, and visual conventions of doll lullabies repeatedly depicted doll play as a child-exclusive activity, implying a lack of adult supervision.25 This highlights the model behavior of the depicted children who know how to play correctly even without the presence of adult authority. However, adult authority is never absent from children’s culture; rather, it exerts its socializing influence surreptitiously in it the structures of musical correctness and musicalized depictions of child behaviors. This is a fictional world in which, in the words of Jacqueline Rose, “the adult comes first (author, maker, giver) and the child comes after (reader, product, receiver), but... neither of them enter the space in between” (Rose 1984: 1-2). The hidden influence of the adult is evident in “Berceuse de la poupée” [The doll’s lullaby], the final piece from Scènes enfantines [Children’s scenes], op. 61 (ca. 1890) by the French pedagogue Théodore Lack (1846-1921). The title page of this composition features twelve framed vignettes, with the righthand panel one up from the bottom depicting a light-haired girl resting alone in a high-backed armchair (see Figure 3). Dark shadows surround her image and her left arm rests over the form of a doll lying in her lap. Lack’s music adheres to lullaby standards, emphasizing simplicity – “Andantino semplice” tempo – and sweetness – using the term “dolce” three times – while the main melody opens with a repeated descending major third that coos and sighs in time with the arpeggiated accompaniment. Lack specifies his programmatic intentions through the use of in-score texts, words or phrases inserted above the musical staff meant to give narrative meaning to the music.26 At the beginning of the piece, Lack writes “Yvonne puts her doll to sleep”27, giving the music an autobiographical intimacy by using the name of his own daughter. Girls playing this piece can imaginatively enter into the scene and its meanings with Yvonne as their musical avatar. At the end of the piece, Lack writes another in-score text that reads “The doll falls asleep and Yvonne too”28. At this point the melodic major third motif continues for several more measures before disappearing “calando” and “pianississimo”.

Figure 3. Detail of Scènes enfantines title page by Théodore Lack

Returning to the cover page illustration with this ending in mind, we can now interpret the positioning of Yvonne’s body as the posture of a sleeping child, eyes closed, head tilted slightly to the left, having succumbed to the soothing effects of her own lullaby play. With this final in-score text, Lack has shifted the piece significantly, yet almost imperceptibly, from a depiction of a child at play to one of a child at sleep. Yvonne had been exercising her creative agency over an inanimate plaything, but when she herself falls asleep, she becomes powerless, an inanimate plaything of an adult, who has placed her in the passive and static position of a doll. To what extent did the music ever truly express the voice of the child? Or does it rather ventriloquize the child in order to give voice to the hidden adult’s aetonormative perspective on childhood?

This adult conflation of the child with the doll takes on the telescopic quality of a mise en abyme in the case of another piece by Lack, Le Roman d’une poupée op. 258 (1906), a remarkable work with words and music by Lack and illustrations by his actual daughter Yvonne.29 Best understood as a “sheet music picture book”, it consists of twelve short piano pieces interspersed among a prose story about a marvelous world of living toys. From the beginning Lack ingratiates himself to his child consumers, promising to delight them with toy shop wonders, while Yvonne’s brightly-colored depictions of contemporary toys appear as headings at the beginning of each piece and are often integrated into the narration as drop caps. The story’s two main characters are Princess Myosotis, a wooden doll with a single dowel for legs, and Captain Sabre-au-Clair, a wooden soldier sitting astride a horse on wheels. The story tells of these two figures playing out an idealized courtship that transitions from the Captain serenading the Princess below her balcony and asking for her hand, to their sumptuous wedding and subsequent honeymoon on the shelf of Italian toys. “How time passes when one is happy!”30 The Princess, now known as Madame Sabre-au-Clair enters into blissful motherhood in the tenth piece “Le Carillon du Baptême” [The baptism bells] with “the birth of a sweet little doll, their daughter, who came into the world saying ‘Papa, Mama’.”31 The following page depicts a lullaby, entitled “Lullaby to put to sleep the doll of a doll” [Berceuse pour endormir la poupée d’une poupée], which Lack narrates: “After this long ceremony, Miss Sabre-au-Clair, somewhat tired, returns to her room, and her mother sings her to sleep with a lullaby in a sweet and tender voice”.32 Yvonne’s illustration depicts the mother positioned in front of a wicker bassinet in which her daughter presumably sleeps nestled out of sight, her arms pointing forward in as near a gesture of embrace as her stiff, jointless arms are capable of. Spanning the page hang four additional doll babies, decorations or premonitions of future offspring (see Figure 4). Lack’s music presents a repetitive descending accompaniment supporting a “semplice” melody, digressing momentarily into a monophonic passage in small note heads to depict the infant’s inner world – “She dreams of her little papa”33 – before recapitulating and ending “pianissimo”.

Figure 4. Illustration by Yvonne Lack from “Berceuse pour endormir la poupée d’une poupée” from Le Roman d’une poupée by Théodore Lack

This blissful scene of ideal childhood and motherhood – as well as girlhood for the potential female pianist – takes an unexpected and melodramatic turn into tragedy. A lengthy paragraph on the next page describes the valiant death of Captain Sabre-au-Clair as the hands of “a band of horrible cannibals”34 who had stormed into the toy store. When she hears of the death of her husband, “Madame Sabre-au-Clair gives an earsplitting cry and falls backwards off the hight of the windowsill with her daughter in her arms onto the parquet floor where both of them break into a thousand pieces! O the fragility of human things!”.35 The composition ends in the pall of dark silhouettes and the mournful tones of a funeral march, fleeting quotes of the happy couple’s opening themes quashed by a final statement of the funerary Dies Irae chant. Girls who play faithfully through this story have been led through the wonders of a toy shop, learning proper ways of playing with dolls, of playing piano, and of performing their girlhood through “prospective states” of courtship, marriage, and devotion to family. The ‘forward-looking mirror’ of motherhood is characterized as happiness itself, providing the ‘good mother’ with fulfillment as she performs a lullaby after performing the social and religious ceremonies expected of her class and heritage. Despite this, the mother is ultimately and completely dependent upon her husband, whose demise causes her to die of grief, taking her baby girl with her, literally dashing to pieces any possibility of a future that did not conform to conjugal norms. It falls to the girl pianist to carry on, accompanying the grim funeral march with the proper pathos and gravity.

5. Finding a “Point of Contact”

The vast majority of imaginative children’s music compositions were written by adult men; women – let alone children – rarely contended with the patriarchal and aetonormative forces that shaped this musical canon. Despite this, the creation of original children’s music could offer women a socially acceptable creative outlet for several reasons. First, the generic marginality and simplicity of children’s music did not compete directly with more ‘serious’, masculine endeavors such as symphonies, counterpoint, and public virtuosity. Second, due to the “bottomless piano-girl market”, the transmission of musical skills at an amateur, domestic level was largely a female enterprise, providing women with some measure of authority as teachers (Solie 2004: 101).36 Examples of imaginative children’s music written by women, therefore, give voice to the negotiation of female agency. Even while conforming to the limitations of patriarchy, these composers, their professions, and their compositions reveal the fissures in the veneer of male-dominated hegemony by adding complexity to the concept of what motherhood, girlhood, and childhood could be. In the case of instrumental lullabies, the lived experiences of female composers allowed them to complicate and subvert the angelic, Romantic ideal of maternal bliss, and to provide musical depictions that shed light on the complications, limitations, and celebrations of motherhood.

American composer Florence Newell Barbour (1866-1946) was born in Providence, Rhode Island and achieved some notoriety as a composer of works for piano, voice, chamber, and chorus. She gave birth to four children between 1892 and 1896, an experience that appears to have informed her depiction of an instrumental lullaby. The final piece from her collection Holland Suite (1912), is entitled “The Dutch Mother’s Goodnight: Lullaby”, which through its various components problematizes the iconography of the ‘good mother’.

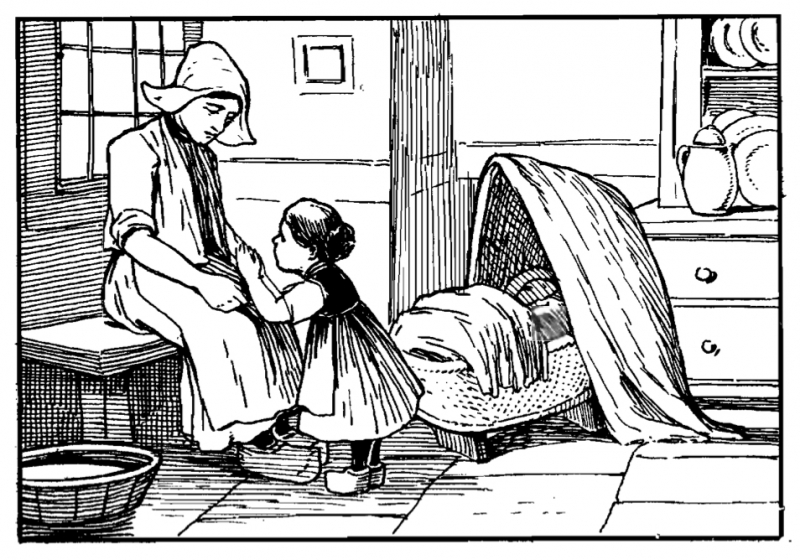

Figure 5. Illustration from “The Dutch Mother’s Goodnight: Lullaby” from Holland Suite by Florence Newell Barbour

Each piece in Barbour’s collection included framed, ink-drawn illustrations at the top-left corner, and the picture for “Lullaby” is remarkable for depicting the complexity of the mother-child dyad in the domestic sphere, rather than adhering to sentimentalized idealizations. We see a simple domestic interior, a kitchen, judging by the dish cabinet to the right (see Figure 5), with a woven basket to the right, potentially containing folded linens. A mother sits on a low bench beneath a window, wearing a Dutch cap with turned up wings, a white apron, and wooden clog shoes. Before her is a young girl, a toddler wearing her own set of small clogs and white apron, her face turned towards the mother and away from a pillow-filled cradle. Mothering children is work, sometimes emotionally rewarding, but also emotionally and physically exhausting, a concept communicated by the mother’s worn expression combined with her rolled-up sleeves. Furthermore, mothering children is only a part of the maintenance of the domestic sphere, demonstrated in the kitchen’s double function as both nursery and laundry room. Lastly, the picture speaks to the potential for struggle and frustration in the lullaby between care-giver and care-receiver; the toddler has turned her back on the cradle and her hands are pressed together in supplication. Unlike illustrations that show only blissful cuddling or compliantly slumbering infants, here the ritual of the lullaby has yet to start and the mother already seems exhausted; the pair seem about to start negotiations. Barbour’s music confirms this by musicalizing their mutual attempts, interruptions, resolutions, and frustrations. What starts “Slowly and tenderly” in F major is frequently derailed by continuous dynamic swells – at times shifting from piano to forte and back within the space of four measures – and features an animated B section in D minor replete with syncopations, accents, ritardandos, and augmented sixth harmonies. The return of familiar material in the A’ section maintains a turgid atmosphere, struggling through a forte passage marked espressivo before gradually settling to a cadence. An additional eight measures act as a coda, with the marking “Very slowly, the good night”. Only now does the child seem ready to settle down to sleep, drifting away from piano to pianissimo and finally to the pianississimo release of a suspended cadence. By balancing musical tenderness and musical struggle, this depiction of mother’s work resists the characterization that lullabies are decidedly quiet and peaceful affairs, offering young girls a fuller understanding of societal expectations and domestic duties.

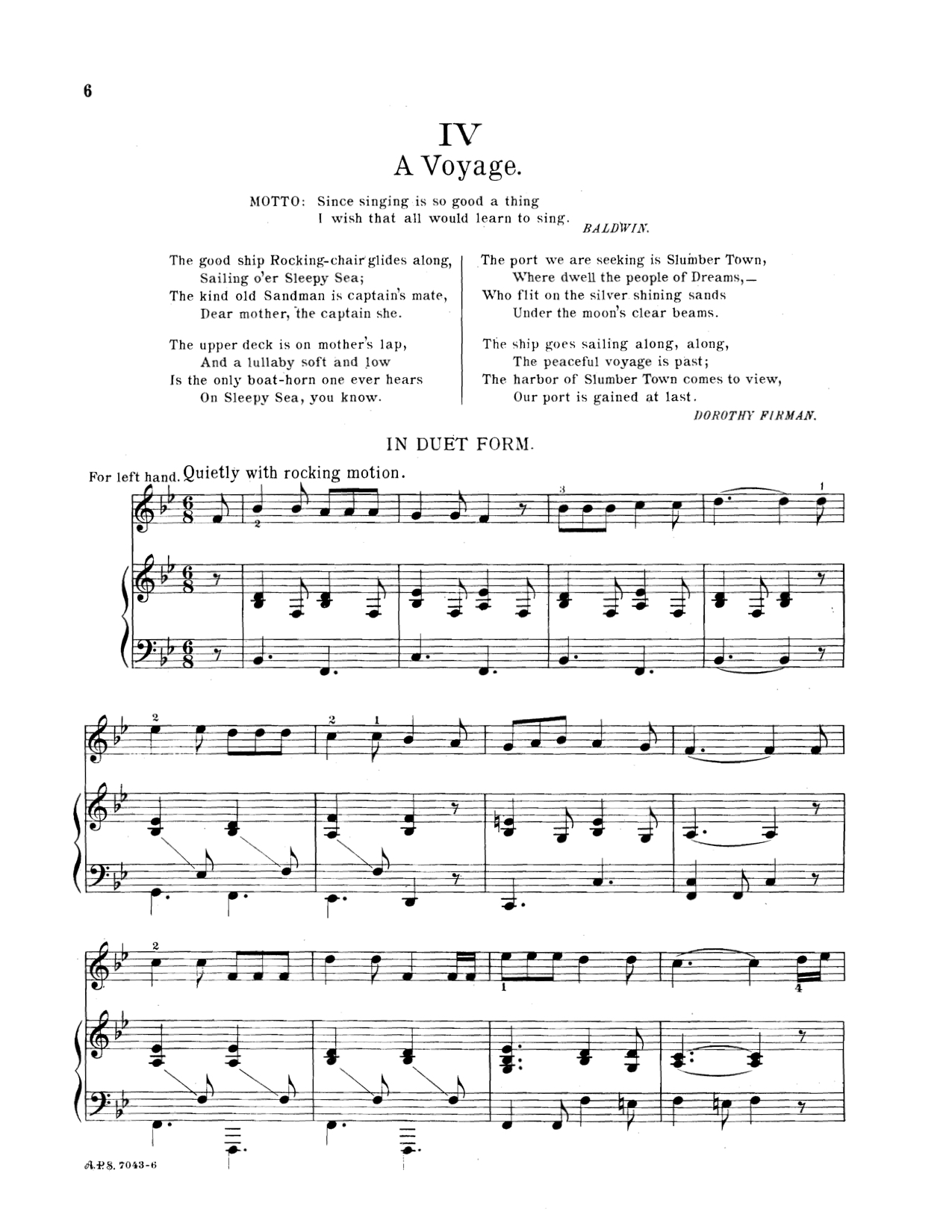

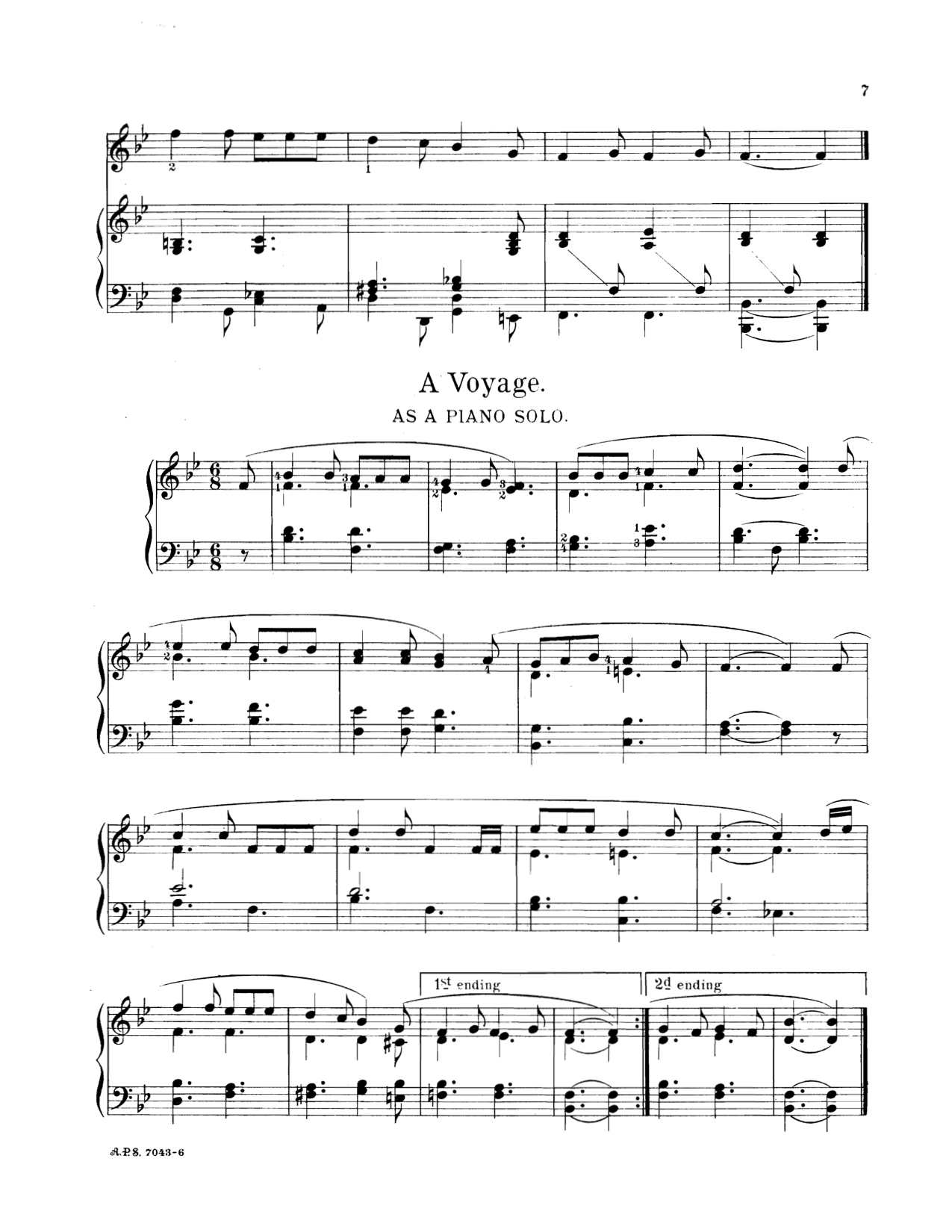

My last example is by American composer Juliet Adams (1858-1951), who composed under the name Mrs. Crosby Adams. Entitled “A Voyage”, it is a veritable constellation of musical possibilities and social depictions, a multifaceted ‘forward-looking mirror’ that reflects the composer’s dynamic understanding of musical education, feminine creativity, and child agency. “A Voyage” abounds with intermedial richness, consisting of a title; an excerpted subtitle advocating the importance of singing; a four stanza lullaby poem with playful, nautical imagery by Dorothy Firman;37 both duet and solo versions of the sheet music including the possibility of singing the words of Firman’s poem to the instrumental melody, and a cover page illustrated silhouette of a young mother and a young boy playing enjoying a rocking chair. (See Figure 6 and Appendix 1). The superfluity of these elements and the possibilities of their interactions paint the musical education of children as a wildly dynamic and non-linear process. Whatever girlhood and motherhood may be, whatever lullabies and piano playing symbolize, Adams explores them with such liveliness and diversity that they offer girls less a mirror and more a kaleidoscope which they can use to creatively interact with the world.

In her 1903 autobiography Adams posed the question “To what end is all this music study, this ceaseless procession of children and young people with music rolls going to and from their lessons?” (Adams 1903: 104). For her the answer lay in a definition of growth and maturation that went beyond images of feminine self-regulation, idealized mothering, and careful handling of dolls. For her, a “musician” contributes to the happiness of their home, their community, and their world. She lays heavy responsibility for this result upon adult music teachers, who needed to find a personalized, empathetic “point of contact” with every student, exercise enormous patience and tolerance, and cultivate the child’s inborn power towards self-expression (Adams 1903: 42). She writes,

Intellectual and moral culture are therefore indispensable to the teacher of music. For to know how to interest the pupil from the very first lesson; to know how to regulate the instructions to meet all circumstances and all varieties of disposition, making it his aim to awaken into consciousness the principle of art, which is surely implanted in the soul of the pupil; to be willing to exercise true patience, that patience which, working always, watches and waits for the results; to hold technical skill second to the artistic principle, notwithstanding the temptation which is constantly presented to make showy, brilliant performers, is surely no easy task, and one for which he can only be trained by careful thought, and study of character. (Adams 1903: 93)

Adams inverts expected aetonormative power dynamics when she insists that it falls upon the adult teacher’s shoulders to successfully teach music to children. For her, it is not enough to offer “prospective states”, but rather to engage in musicking while meet them as human beings in mutual and reciprocal growth. In this way Adams especially offers a new paradigm for how music functions as a socializing tool that has important ramifications for the definitions of childhood, girlhood, and motherhood in the nineteenth century and beyond.

Figure 6. Detail of Four Duets for Two Beginners title page by Mrs. Crosby Adams

Conclusion

Subversive and complex pieces such as those by Barbour and Adams proved to be the rare minority for instrumental lullabies. For the most part this theme continued to be rendered through the same placid and respectable features as before, depicting the idealized images of childhood, girlhood, and motherhood that suited the aetonormative and patriarchal order. These musical characteristics remained largely unchanged even as instrumental lullabies continued to travel through space and time. Idealized motherhood thrived in the lullabies of the educational repertories of the Soviet Union,38 and continue to this day in contemporary method books in the United States.39 Perhaps the longevity of this music attests to the continuation of unspoken social boundaries that order the definition of children and women. It is worth considering Philippe Ariès’ observation that “children form the most conservative of human societies” (Ariès 1962: 68), and by critically investigating the structures and roles of children’s culture within adult culture that we can reconsider the usefulness of these outdated and coercive ideologies. Undoubtedly the lived experiences of girls interacting with these lullabies have engendered and will continue to produce a diversity of reactions, establishing a diversity of relational meanings; the analyses that I have posited and connections I have drawn between the musical and social meaning-making constitute only one possible interpretation. Yet perhaps the mere possibility that children’s music could play such a part ought to be enough to make us think twice.