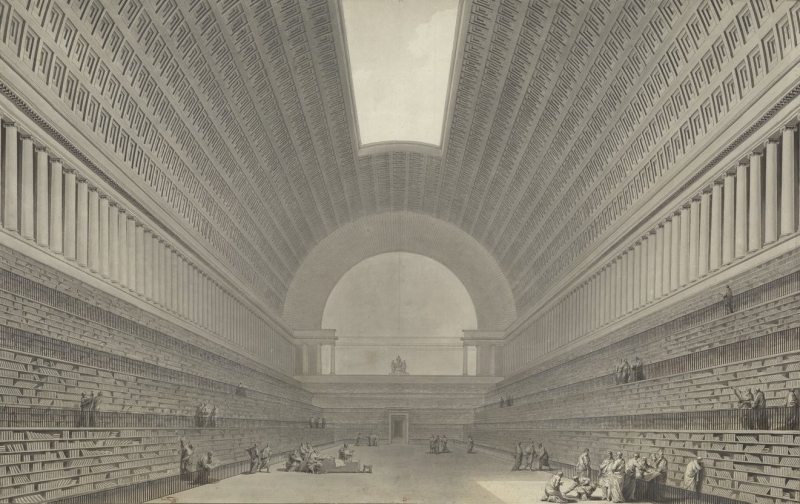

Describing his project for the Bibliothèque du Roi, a large library in Paris housing the royal collection, French architect Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728-1799) stated his ambition to execute “the sublime conception of Raphael’s School of Athens”.1 Indeed, the perspective view of the interior of his proposal features an impressive vault under which men in ancient costume discourse, recalling the philosophers in Raphael’s celebrated fresco (Figs. 1-3). The anachronism, here, might appear obvious: figures from the past pace the halls of an architectural project for the future. However, this apparently simple observation is based on a specific vision of historical time that does not necessarily match the designer or his contemporaries’ understanding of this picture. The present article will pursue an analysis that interrogates the concept of anachronism – and its validity within different intellectual and perceptual frameworks – by replacing the project within Boullée’s architectural thought, within a specific visual culture, and within eighteenth-century conceptions of time. We will thus often – but not always – proceed beyond the concept of anachronism, to reveal how the juxtaposition operated by portraying ancient philosophers under a modern vault opens up interpretations far richer – and more interesting – than the simple “error” that is often implied by this notion.2 Indeed, a detailed examination of temporality within this widely appreciated yet little-studied image will allow us to uncover several key conceptions underlying the library project, the French architecture of the late eighteenth century, and ultimately this cultural context’s understanding of its own position within history.

Figure 1. Étienne-Louis Boullée, Perspective view of the Bibliothèque du Roi reading room, ink and grey wash, before 1785, Paris.

Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Figure 2. Raphael, The School of Athens, fresco, 1509-1511, Rome, Vatican Palace.

Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

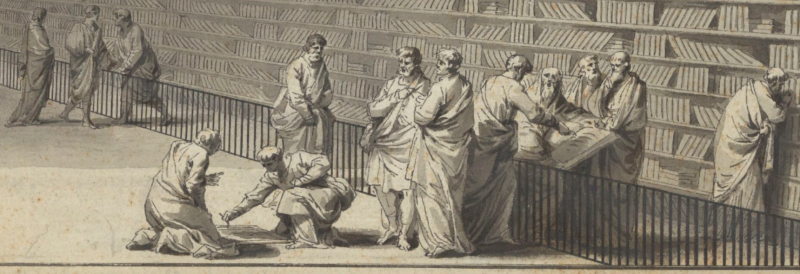

Figure 3. Étienne-Louis Boullée, detail from Fig. 1 (right foreground).

Bibliothèque nationale de France.

1. Media and Temporality

Boullée’s design for the Bibliothèque du Roi appears in two sets of drawings, which only feature minor differences in their portrayal of the gallery’s interior.3 Some of these images were published as a print series,4 accompanied by a short text that would later be reproduced – with minor variations – in Boullée’s treatise Architecture. Essai sur l’art, which remained unpublished until the twentieth century.5 The architect’s design for the library is one of the most practical and realistic within the series of projects for public buildings – probably functioning in part as pedagogical models for his students – that occupied him during the last, and most celebrated, phase of his career. While his other works from this period were often conceived on an impossibly large scale, and imagined either within an entirely empty space or an imaginary topographical setting that perfectly suited the project’s volumetry, the library project was site-specific: indeed, Boullée suggested using the walls of the existing Bibliothèque’s courtyard (which, to this day, contains the Bibliothèque nationale de France’s Richelieu quadrangle and reading room) as foundations for the wide barrel vault that can be seen in the picture, entirely made of wood. His description insists on the constructional simplicity and low cost of his proposal, no doubt in the hope that this design – among his many grandiose visions – would be the most likely to be erected.6 This realistic quality and destination constitute the framework within which the issue of anachronism must be analysed: in the architect’s purely imaginary visions, by contrast, the dates of the buildings remain fictional, or even unknown (are they set in modern times? in Antiquity? or in an imaginary, non-historical context?), and temporality can thus function very differently than in the more strictly-grounded Bibliothèque.

The library project, though far smaller than many of Boullée’s other conceptions, seeks a similarly impressive effect to his gigantic imaginary monuments: as Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos has pointed out, the architect’s impossibly large designs often function in pairs with smaller – but not necessarily less grand – proposals.7 Boullée has here succeeded in inserting an iteration of his ideal conception of space into the normally disordered and constrained reality of Paris, an achievement that would probably have led visitors to forget the complexity of their urban surroundings and to enjoy the grandeur of this self-contained interior, thus loosening their sense of location within geographical space and historical time.8Yet, and even more so since the gallery was never built, perceptions of this project and of its designer’s conception are strongly mediated by Boullée’s image, and chiefly by its inclusion of ancient figures. The latter, bringing extremely rich cultural and intellectual themes into the scene, inflect our understanding of the architectural design itself: an analysis of the library project must thus include a discussion of Boullée’s image, precisely, as a picture rather than purely as a work of architecture, especially as far as its anachronisms are concerned.

This entails that the perspective view of the library must be examined both alongside Raphael’s School of Athens and within a larger corpus of architectural images from its own day, subject to specifically pictorial compositions and temporalities. This line of enquiry has not yet been sufficiently pursued in the extant scholarship on Boullée, which has largely ignored the later eighteenth century’s widespread interest in architectural representation.9 The success attained in the 1770s and 80s by Hubert Robert’s ruin paintings, attested both by their extremely high selling price and the critical acclaim they enjoyed, reveals the popularity of this genre.10 Perhaps yet more significantly for our argument, one of the key themes of Robert’s oeuvre is a play on complex temporalities. There was also a frequent overlap between the work of painters and of architects: the latter produced attractive perspective views of their projects, but also of imaginary buildings, gardens, landscapes and ruins.11 Boullée himself had initially wished to become a painter, rather than an architect, and this ambition remains visible not only in the pictorial conception of his drawings, but also in his imitation of Raphael – then regarded as the absolute model for young painters, who were often tasked with copying his works as part of their academic education (incidentally, Boullée’s interest in the School of Athens is apparent not only in his library project, but also in the sculpted groups adorning the pediments of several of his other designs).12

Besides painting, Boullée’s works should also be compared to another (quasi-pictorial) medium: the theatre,13 then immensely popular, to the point of constituting an essential component of the French elites’ visual culture. Boullée would have been familiar with a typology of drawings, mostly penned by architects, showing projects for stage sets inhabited by figures in theatrical costumes (Fig. 4).14 Since the plays’ action was set in Antiquity, and the actors wore togas or crested helmets, but the architecture was in the taste of the late eighteenth century, these images are often remarkably similar to the library picture, both in terms of their visual effect and of their anachronisms. Boullée reinforced this resemblance by representing his gallery, which would certainly have functioned in part as a reading room, unrealistically void of furniture. The open space thus created in the drawing resembles a theatre stage occupied by actors, which was the spatial typology within which eighteenth-century viewers were accustomed to see ancient figures.15

Figure 4. Charles de Wailly, Stage set project for Racine’s Athalie, ink, grey and brown wash, 1783, Paris.

Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Within the present discussion of Boullée’s library project, the specificity of pictures (as well as pictorially-conceived theatrical scenes) lies in their ability to represent temporalities more easily than built architecture can. It is true that a building can deceive its viewers as regards its construction date or the dates of its various parts: indeed, this was the period when artificial ruins set off to conquer the landscape gardens of France. However, it is more difficult for architecture to transport its viewer to a fictional or historical present, as images do: an observer of the library picture may quite easily accept that it represents a moment set in Antiquity, but a visitor to the actual space – if it had been completed – would at best have experienced a somewhat imprecise sense of removal from their own time, rather than believing to have been transported to the period of Plato. Boullée, perhaps due to his inclination for painting, created a drawing that plays with the possibilities of the medium and the complex temporalities that it allows. The latter are naturally also the necessary conditions for Raphael’s representation of an ideal past, and for paintings by Hubert Robert – such as The Port of Ripetta (Paris, ENSBA) – that combine elements of European history in so complex a manner that their fictional present is situated entirely outside of historical time. As concerns Boullée, however, while the study of his perspective drawing as an image is an oft-overlooked dimension of his work that must be carefully reconsidered, its simultaneous status as picture and proposal for a future reality raises further implications that will lead us to better understand his conception of the entire project.

2. The Ancient and the New Athens

The relation between Boullée’s library picture and Raphael’s School of Athens requires that these two images be set side-by-side for more detailed study. While the general similarity between their figures has been noted, Boullée – or perhaps draughtsman Jean-Michel Moreau, upon whom he often relied to complete his drawings16– did not directly copy the Renaissance painter’s philosophers. Only the group in the right-hand foreground, surrounding the man holding a compass, and the figures sitting around the table, could be interpreted as loose quotations of the fresco (Fig. 3). Besides these examples, not only are the figures’ poses and spatial relationships different from Raphael’s, but their faces are also far less distinct from one another in terms of hair colour, age, type, and expression. While the painter’s philosophers are the main focus of his fresco, and he has invested time and energy into detailing and varying each figure’s pose and facial features, those in the architect’s drawing are small, modest sketches aiming to animate the architectural space and refer to a general idea of philosophy rather than to rival the work of the most celebrated painter of modern times.

This difference in the function of the figures entails that the viewer will observe these two pictures in dissimilar ways: in Raphael’s fresco, the titles of the books held by Plato and Aristotle (Timaeus and Ethics) are inscribed within the picture, thus clearly indicating the identity of their bearers and inviting viewers to pursue their identification of the other philosophers. Indeed, eighteenth-century descriptions of the School of Athens17 (except those by particularly architecturally-minded commentators) are chiefly interested in the figures, and in the meanings conveyed by the latter.18 Boullée’s picture, inversely, is essentially a presentation of an architectural project, and striving to identify his philosophers would make little sense. Any attempt to directly transpose art-historical interpretations of Raphael’s fresco onto Boullée’s drawing would therefore be far too simplistic, since it would ignore the significant differences between sixteenth-century allegory and eighteenth-century architectural and historical imagery (and thus would likely constitute a scholarly anachronism!).19

Despite the loose quality of Boullée’s quotation, it remains clear that the figures in the library picture rely on the viewer’s visual culture to refer, perhaps not to individual ancient thinkers, but to the general ideas conveyed by Raphael’s fresco. Thus, the group of philosophers simultaneously constitutes a glorious reference to ancient Greece and indicates a compilation of the knowledge developed by various scholarly fields: as such, it represents the future contents of the library.20 This idea of bringing together the sum of human knowledge naturally resembles another great endeavour of the French Enlightenment, the Encyclopédie. Besides the members of the Greek school of philosophy, it also recalls the famous libraries of Antiquity, and chiefly that of Alexandria, which remained a celebrated cultural reference.21 Indeed, Boullée’s picture articulates these two representations of a sum of knowledge: where Raphael represents the latter only as a group of Greek scholars22, the architect’s drawing doubles this with a library, and if the project had been executed, only the books would remain. The figures’ function within the library picture is thus not only to underscore the similarities between Raphael and Boullée’s architectural conceptions, but also – according to this interpretation – to provide a transitional image revealing how Raphael’s representation of a group of philosophers is replaced, in a real library, by the books authored by these same figures.

A similar idea is expressed by Boullée in his theoretical essay, where he argues that a library’s user is “inspired by the spirits of famous men” and encouraged to “walk in the footsteps of great men”:23 a physical presence of these revered minds within the library is thus both suggested by the architect’s language, and fictionally represented in his perspective view.24 Nevertheless, this interpretation must be further qualified by pointing out that the library picture is by no means the only architectural drawing from this period to include ancient figures. Besides examples due to other architects – including Charles de Wailly’s famous representation of his project for the Odéon theatre, exhibited at the Salon of 1771 – most of Boullée’s pictures also contain ancient figures.25 The latter have merely been adapted, in the library image, to all appear as adult males recalling Raphael’s philosophers, leaving out the women and children in ancient dress that often grace his other drawings. The togas in Boullée’s representation of the library project thus cannot be explained only as a reference to Raphael, or as an imaginary presence of ancient authors: further, parallel interpretations of this picture’s unclear temporality must be sought, acknowledging a complexity that is fully consistent with Reinhart Koselleck’s demonstration that multiple perceptions of time can coexist.26

A first point to be made is that Paris, during this period, was often called “The New Athens”. A book with this title was published in 1759 by Antoine-Martial Le Fevre, who justified the phrase by tracing the origins of French scholarship to ancient Greece, claiming that his nation was the true heir to the ancients, and that its intellectuals had attained the level of the greatest cities of Antiquity: “Paris today is in no way inferior to the scholars of Athens and Rome”.27 The formula was used frequently during the following decades, not least as the title for a chapter of Louis Sébastien Mercier’s Tableau de Paris, in which he claimed that men sought the praise of Paris (then granted chiefly to Voltaire, Rousseau and Frederick the Great), in the same way they had once wished for the approbation of Athens.28 Moreover, celebrated modern philosophers were often represented in ancient clothing: this was already the case in several portraits of Montesquieu, depicted in profile like the emperors featured on coins or medals,29 while the many statues of Voltaire and Rousseau from Houdon’s studio often show them in togas. When the remains of the two latter philosophers were moved to the French Panthéon during the Revolution, effigies of them in ancient costume were carried through the streets of Paris.30

This perception of Paris as a new ancient city rested upon a cyclical interpretation of history, whereby Antiquity could be – indeed was being – recreated. Naturally, this vision bears significant implications for the analysis of the ancient figures animating eighteenth-century architects’ drawings: Boullée’s library project provided an updated version of Raphael’s imaginary “Athenian” building, to be erected in the “New Athens”.31 The figures in his pictures could be interpreted not only as the Renaissance painter’s ancient Greek philosophers, but also as Paris’s modern intellectuals, forming a “School of the New Athens” dressed in ancient costume like Montesquieu, Rousseau and Voltaire.32 Furthermore, since Boullée’s design is obviously a project for the future, his philosophers are perhaps not only to be understood as those of the past – whether recent or ancient – but may be set in times to come: according to this interpretation, his drawing constitutes a statement of confidence in the future evolution of French scholarship, while simultaneously suggesting that his library will be the most appropriate environment for these future intellectuals, by fulfilling their documentary requirements, by serving as a space for reflexion, discussion and the development of great ideas, and by providing an architectural setting worthy of their grand achievements. This positive outlook is fully coherent with the idea of a national regeneration, in other words a period of national progress in the near future, which became increasingly popular during the 1780s and was to play an important part in the French Revolution.

While this interpretation underscores the drawing’s position at the nexus of complex relations to past, present and future, it must still be further qualified. The modern scholars using the library would not be wearing ancient costumes, and thus the image does not constitute an exact representation of a possible future. Indeed, the period’s tendency to show great modern philosophers in ancient clothing bears significant implications regarding temporality: by declaring them worthy to dress like Plato or Aristotle, it separates these figures’ representations from the reality of their eighteenth-century costume. The cyclical vision of history may have claimed that the nation, and in this case its scholars, had attained the exalted level of the ancients, and this was expressed by the ancient costumes in which philosophers were represented, but the actual clothing of the time was not concerned by this cycle. There were, admittedly, attempts to apply this grand vision of history to costume by drawing inspiration for new fashions from ancient models, especially in the case of women’s dresses, but also in some male garments: this is revealed, for instance, in Jacques-Louis David’s designs for Revolutionary magistrates’ uniforms.33 However, toga-like costumes, being unsuited to modern European lifestyles, naturally never caught on. The cyclical vision of history was applied to the nation, to its philosophical qualities and – as we shall see – to its architecture, but could not be fully transferred to its use of everyday costume: in other words, the idea of a cycle concerned some aspects of daily life in France, but not others.

Nevertheless, the use of ancient clothing in images and during festivals indicates that the modern French liked to imagine themselves – or the most worthy among them – dressed as ancients: the cyclical vision of time, although it could not be applied to the everyday reality of costume, at least functioned in France’s imaginary perceptions of its own inhabitants. The future users of Boullée’s library would most likely not be wearing ancient clothing, but their contemporaries may well imagine them doing so. This interpretation can very well exist alongside those suggested above, and interact with them, thus forming a complex network of historical perceptions within which the notion of “anachronism” – earlier used in a description of the architect’s drawing according to twenty-first century conceptions of time – will require renewed consideration.

3. Architecture: Equalling or Surpassing the Ancients?

Historical visions have so far been analysed in regard to perceptions of the greatness of nations, of the quality of their philosophy and of the style of their clothing. But in the case under study, their impact on understandings of another human creation – architecture – is perhaps yet more complex and significant. The multiple relations of architecture to temporality form a particularly labyrinthine web, simultaneously encompassing the theoretical positions formulated by architects, the specificities of their buildings and drawings, and the comments on architecture made by members of a broader public. During the period under consideration, this situation is complicated yet further by the cultural importance granted to architectural painting and the emergence of a widespread interest in ruins. The latter suppose a distinction between the period of erection of a building and the moment in which it is seen or represented, creating a temporal relation which can easily be manipulated, both by painters and by designers of the artificial ruined pavilions then being erected in landscape gardens around Paris. Although Boullée’s gallery shows no sign of decay, his period’s taste for ruins does create a context where the potential complexity of architecture’s relation to time would have become strongly apparent.

Boullée’s drawing, hitherto analysed chiefly as an image, must now be examined as an architectural project, and replaced within the architectural thought prevalent at the time of its creation. Once more, the idea of a historical cycle is key to a first exploration of the temporality of French perceptions of architecture. Under the reign of Louis XIV, Augustin Charles d’Aviler spoke of the “antique [architecture] we have today” – which, replacing the Gothic, ensured a return to the glorious days of the ancients34. During Boullée’s lifetime, Pierre Patte remarked that several of the proposed “ideas for embellishment of this capital, and projects for squares [dedicated to Louis XV], would have honoured the most skilled architects of Antiquity.”35 Likewise, Marie-Joseph Peyre later stated that “the porch of the École de Chirurgie is even more conform [than other contemporary buildings] to the manner of the ancients”,36 and the Almanach de Versailles noted that the recent church of Saint-Symphorien had “the shape and the aspect of ancient temples”.37 Peyre further explained his position by stating that he wished to identify “the principles of the Greeks and Romans” and then “develop [them] and … appropriate them for ourselves.”38 During the same years, Hubert Robert painted imaginary ancient-looking, partly ruined architectural environments, within which he often placed decaying monuments that recalled the architectural vocabulary of his own day: constructions from these two eras were thus perceived to be interchangeable.39 The most celebrated buildings of the time were therefore understood, on a certain level of consciousness, as ancient constructions, and their architects were perceived not only as imitators of the ancients, but – in a sense – as having become ancients themselves: according to this interpretation, Antiquity had become contemporaneous. This is perhaps most clearly explained in Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s treatise: “Taste is invariable, it is independent from fashion. The man of genius gains only that which the centuries that preceded him had lost”.40 Thus, architectural value is an eternal, unchanging ideal that is only attained by a small number of privileged societies, including ancient Greece and Rome, as well as Renaissance Italy and modern France. Ancient taste is therefore identical to the best modern taste, which is also, put quite simply, good taste.

This commonly held eighteenth-century view allows an interpretation of Boullée’s drawing as a representation of a timeless architecture, simultaneously ancient and modern (and, naturally, also typical of the Italian Renaissance through its reference to Raphael, another artist then considered to have attained this eternal quality). Incidentally, this may also apply to the figures, whose ancient costume was the only style of clothing that could evoke timelessness, an interpretation that is confirmed by the aforementioned use of ancient dress in representations of modern great men. Following this line of analysis, if Boullée’s drawing is indeed a representation of an eternal, timeless (or “out-of-time”) environment – and despite its simultaneous status as a perspective view detailing a modern project – then the initial premise of this article must be reconsidered: the elements of this picture, far from being anachronical, function within their own, coherent but ahistorical time. Indeed, an anachronism can only exist within an understanding of time that supposes key differences between the culture and society of historical periods, even when the latter imitate one another’s intellectual or formal creations. In other words, anachronisms cannot exist within the timeless quality to which the summits of a strictly cyclical history constantly return.

Nevertheless, this idea of timeless form – though it is frequently encountered in eighteenth-century architectural thought and allows a coherent reading of Boullée’s image – functions in parallel with other, conflicting visions of historical time, illustrating the vitality of French Enlightenment discussions of this issue. Boullée’s own treatise argues that the rich and varied possibilities of architectural expression that he seeks to discover have been historically neglected, and are only beginning to be explored in his own day: “am I not, in a sense, correct to point out that architecture remains in its infancy …?”41 Here, the architect appears to be fully in step with the idea of progress, which is characteristic of some strands of the Enlightenment, and underlies the notion of national regeneration that became widespread during these years.

However, Boullée’s position is less distant from the theory of historical cycles than might appear in this particular passage. Indeed, throughout his theoretical writings he cites Greek architecture as a model, and his projects almost always contain or even constitute clear references to ancient architecture.42 Moreover, his discussion of the Bibliothèque du Roi explicitly states his intention to realise the architectural conception of Raphael’s School of Athens, which the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries interpreted as a Renaissance attempt at representing an ancient space (a Greek “gymnasium” – or school for the development of mind and body – according to Roland Fréart de Chambray).43

Thus, though Boullée set himself the task of improving on the ancients, this idea should be understood within a cyclical conception of architectural history. His treatise suggests returning to an idea of Antiquity, but exploiting its full possibilities to an extent unexplored by the ancients themselves: the cycle may be rising, rather than returning to its earlier maximum. He remains close to other architects’ aforementioned intention to identify the principles of the ancients and appropriate them for modern use: in other words, not to simply reproduce the forms of ancient buildings, but to understand their underlying rules and investigate the possibilities opened up by the latter for modern design. This process might lead to results that may well be slightly different – indeed, slightly better – than ancient architecture. According to this conception, Boullée’s knowledge of historical architecture has led him to design a gallery that is close to ancient principles, but proceeds even further than Antiquity in its exploitation of architecture’s potential for grandiose perspectives.

Boullée’s statement that architecture has not progressed beyond its “infancy”, and that it thus remains possible to improve on ancient models, may partly constitute an acknowledgement that his own designs should not be expected to resemble the latter too exactly. Indeed, he did not attempt to reach accuracy of form or detail in his references to Antiquity, despite living in the second half of the eighteenth century, when numerous representations of ancient sites in the Eastern Mediterranean became available. Significantly for our discussion of the Bibliothèque project, this new documentation soon led scholars to pay more attention to the differences between Greek and Roman architecture.44 Boullée was certainly aware that the Greeks did not build large arches or vaults, and therefore – as the reader will no doubt have noted – that the ancient Athenian philosophers never set foot in any structure remotely resembling his library, or Raphael’s imaginary gallery.45 In other words, Boullée would have known that the architecture in Raphael’s School of Athens was wildly anachronical (moreover, the anachronism within Raphael’s group of figures – philosophers who lived during different periods – was by then common knowledge, having been mentioned in widely-read works by Roland Fréart de Chambray, Giovanni Pietro Bellori, and Roger de Piles46). While it has been pointed out here that the notion of anachronism was not meaningful within certain eighteenth-century visions of history, we have now reached a conception of time within which this concept was used. None less than Diderot, commenting on Hubert Robert’s paintings, urged the artist to follow this linear vision of history, avoiding what may be described as anachronisms:

Travel the entire planet, but may I always know where you are: in Greece, Egypt, Alexandria, Rome. Embrace all periods; but may I never ignore the date of a monument. Show me all genres of architecture and all types of buildings; but with some characters that specify the places, the mores, the times, the manners and the people. May your ruins, in this sense, be also erudite.47

Such ideas will appear familiar to the reader, since they form the uncontested basis for understandings of history developed since the nineteenth century. They operate in conjunction with the idea that artistic form is determined by the conditions and constraints present in a given society, and that an accurate recreation of the architecture of a past era is very rare. During the last decades of the eighteenth century, other critics and art theorists increasingly began to demand that painters’ works reflect a detailed knowledge of the architecture, furniture, costume and even hairstyles favoured by specific historical periods.48 Nevertheless, Boullée, operating within the same context, included ancient figures both in the library picture and in other representations of his architectural projects: whether or not his contemporaries raised the issue of anachronism when discussing these images, it was clearly not of concern to him within his artistic creation. Yet, while it is clear that Boullée was not working within our strict present-day conception of time, it is important to point out that when his projects were drawn, the detailed study of the evolution of artistic forms in historical time – and hence the idea of anachronism – was already becoming available, alongside other understandings of temporality.

Finally, though Early Modern France’s vision of history was dominated by the relation between ancient and modern times, any discussion involving the reception of the School of Athens must also bring in Raphael and his own historical period. Indeed, the reading-room image – a modern French reinterpretation of an Italian Renaissance fresco, which was in turn inspired by ancient Roman architecture but purported to show the greatest hour of Greece – brought together the four summits of Western or even human history, as defined within the cyclical vision established by Voltaire in his Siècle de Louis XIV.49 This process, uniting in one place – Boullée’s project – the four greatest cultures in history, can be read both in terms of the building’s form and of its function, since this “bringing together” would have been present not only in the library’s design but also in its contents (one is reminded of the list of cities later inscribed on the vault of the Bibliothèque nationale’s oval reading room, symbolically featuring Athens, Rome and Paris at three of its cardinal points, with London filling in the fourth).

Coming back, more specifically, to Raphael himself, it is important to point out that Boullée’s drawing has not only inherited formal qualities from the Italian painter’s fresco, but also the features that have formed the basis of the present investigation of its temporality. Naturally, Boullée’s drawing would have been understood solely within eighteenth-century visions of history, and it is not our purpose here to identify in it a remnant of sixteenth-century conceptions of time, which would notably have included a strong religious strain.50 Nevertheless, the presence of Greek philosophers under a barrel-vault – whether or not it bothered Boullée and his public – stems from the imitation of the earlier artist’s fresco, meaning that the architect’s very selection of this particular model lies at the root of the present discussion. While Boullée drew inspiration from the School of Athens due to the qualities of its architectural background, the force of its idea, and its suitability to the site he had in mind, the revered status of the fresco was certainly also a key reason for his choice: Raphael, of course, was then widely considered to be one of the greatest artists of modern times, and his cultural authority, which likely impacted both Boullée’s conception and his contemporaries’ reactions to the drawing, must not be overlooked. The architect and his public would not only have seen the library project and drawing as a dialogue between Antiquity and modern France, but also as a reference to a Renaissance painting that had become one of the most celebrated images in Western culture. The exalted status of the School of Athens would thus have contributed to the legitimation of Boullée’s proposal.

This reminds us that the idea of Antiquity, during the Early Modern Period, was heavily mediated by the Renaissance, and especially by its painters and their representations of architecture: Boullée himself, as well as his teacher Jacques-François Blondel, recommended using Raphael’s images as models for architectural projects.51 Several painters also referred to the School of Athens in their works,52 including Hubert Robert, whose Finding of the Laocoon (1773)53 recalls Raphael’s fresco both through its architecture and the group of figures in the left foreground: Boullée was by no means the only artist of his time to draw inspiration from the School of Athens, which then constituted a commonly available model for attempts at portraying an ancient environment.

Besides this standard vision of Antiquity mediated by Italo-French pictorial tradition, the study of actual ancient sites was gathering pace, producing increasingly numerous images of real Greek and Roman architecture, which formed an alternate idea of Antiquity. Thus, Boullée’s models for the gallery’s decoration may have included features from the Pantheon’s interior, as well as the Roman cryptoportici drawn by Piranesi, and perhaps the monumental avenue at Palmyra and interior of the temple of Bacchus in Baalbek (eighteenth-century prints insisted on these last two examples’ long colonnaded spaces ending in arches or serliana).54 Once more, these references were used not only by Boullée but also by several other artists from his time, including Hubert Robert. Formal resemblances between works by Boullée and the latter artist are often striking, likely indicating an exchange of artistic ideas: the reading-room’s lateral steps, serliana on a high base and part-subterranean character strongly resemble Robert’s contemporaneous Architectural Landscape with a Canal (1783),55 which perhaps also draws upon the Palmyra avenue.56 Boullée and his period thus had access both to the Renaissance vision of Antiquity and to a new, documentary one, but also transformed these two visions according to their own architectural intentions and to the new ideas developed by their colleagues: it is from this intricate network of forces – merging, inflecting or opposing one another – that the temporal complexities of late-eighteenth-century architectural images emerge.

The avenues of thought explored in this analysis of Boullée’s drawing constitute multiple alternative explanations of its temporality, based on eighteenth-century French visions of historical time, which may well have coexisted within the architect’s conception and his public’s perceptions of the image. The present article, setting out to reveal the pitfalls of an analysis of this eighteenth-century drawing according to twenty-first-century notions of time, has attempted to replace the latter by those current during Boullée’s lifetime. Yet, by so doing, it has inevitably led the issue to appear more complex than it would have seemed to the architect and his contemporaries, for whom the interplay of these temporalities – being rooted in commonly accepted discourses – would have remained far more organic. After these theoretical enquiries, it is on a more straightforward note that this investigation will conclude, bringing the discussion down to the more practical working of Boullée’s project and its representation within a social environment. Indeed, the temporality of the Bibliothèque du Roi drawing played a key role in legitimizing his project for the public, as images and stage sets often did throughout the field of Early Modern architecture:57 pictures purporting to represent ancient structures showed buildings that, in reality, closely resembled the designs developed by architects of their own day. Thus, these images provided imaginary, inexistant antique precedents that would justify new projects through their (largely fake) historical authority. While several examples from Boullée’s period might be quoted here,58 his reading-room drawing is especially interesting in that, by inserting toga-clad philosophers into his composition, he is applying this process to his own project: the latter is legitimized by being set in Antiquity and presented as a building that could have been designed, used and valued by the ancients themselves. The project’s architectural design, pictorial model, and underlying concepts regarding time, philosophy and the nation, are thus all tied together within its creator’s own presentation of its appearance. Boullée, in the first lines of his treatise, argued that architecture is not the “art of construction” but a “production of the mind”:59 his gallery picture, thanks to – rather than despite – its temporal complexity, expresses the generative idea of his library project far better than the completed building ever could have.