Reverse Anachronism: Excluding the Present from the Past

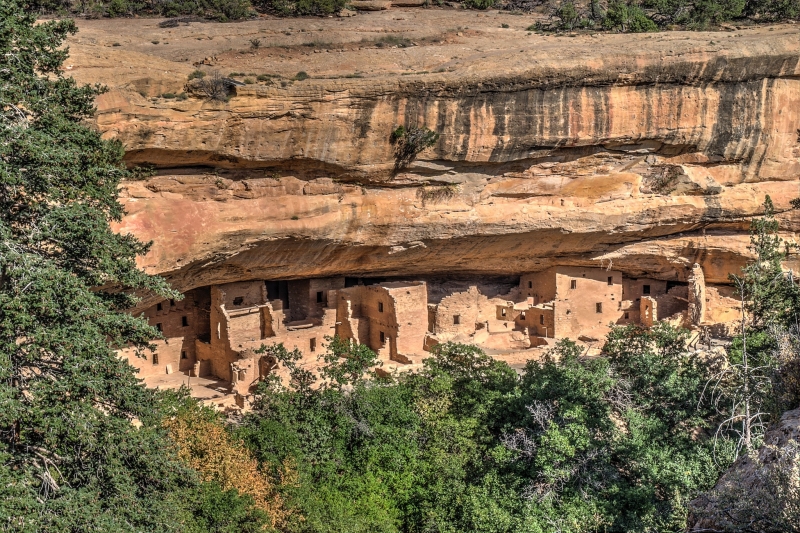

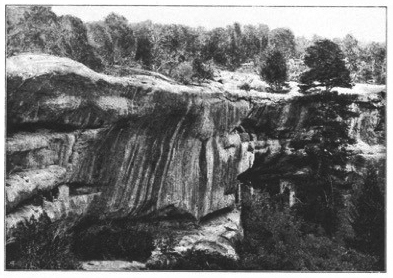

In Indian Country, God’s Country, a recent study of the development of American Indian historical sites as national parks, Philip Burnham discusses how Mesa Verde National Park, located in southwestern Colorado, presents unique challenges for indigenous peoples seeking to assert more control over their cultural patrimony and to reap a larger share of the economic benefits of sharing it with others. Mesa Verde contains some of the most recognizable ancient ruins in the U.S., including the so-called Cliff Palace and Spruce-Tree House, sites occupied and then abandoned by Ancestral Puebloans in the thirteenth century (figures 1 & 2).1 The passing of NAGPRA (the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) in 1990 promised a new era for indigenous peoples in the United States by providing formal legal means for the return of human remains and artifacts held in museum collections, as well as a greater voice in decision-making and profit-sharing at physical sites. However, as Burnham points out, the fact that descendent tribes of the original Mesa Verde inhabitants, such as the Hopi, no longer live in its vicinity has complicated efforts to take advantage of NAGPRA. More specifically, “NAGPRA doesn’t provide guidance on how to eliminate tribal claims that are weakest,” influencing non-Puebloan tribes residing near or even far away from Mesa Verde to argue for some connection to the site (Burnham 2000, 256; Swidler 1997). On the one hand, nearby Ute are motivated to claim a connection with these ruins in order to receive such immediate economic benefits as employment and a share of ticket sales. On the other hand, though, Navajo in entirely other parts of the Southwest have asserted a cultural affiliation with Ancestral Puebloan remains generally in order to prevent Pueblo-descended peoples, such as the Hopi, from compromising Navajo sovereignty within their own reservations by overseeing the disposition of remains located within them. Most of all, though, the increasingly commercialized park itself has an obvious monetary interest in preventing Puebloan tribes from asserting such an exclusive tribal claim, deeming it far better to negotiate with several weak claimants rather than a single strong one.

Figure 1. Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park, CO (ca. 1190-1260 CE).

Figure 2. Spruce-Tree House, Mesa Verde National Park, CO (ca. 1210-1280 CE).

For some parties today, then, both native and non-native, there is an incentive to disconnect Mesa Verde from any strong connection to recent history, to generalize its significance as an ancient indigenous settlement. The disconnection of past and present Puebloan cultures relative to specific sites like Mesa Verde has in fact become a major issue within Southwestern archaeology. For many contemporary Puebloan societies, the whole notion that Mesa Verde was abandoned at all is seen as problematic because it discourages the sense of a continuous culture over time.2 Conversely, some writers argue that the conceptualization of a stable, and hence unchanging, indigenous culture risks reintroducing an outdated notion of primitive or prehistoric identity (McGhee 2008, Oland, et al 2012). This essay examines how the establishment of the Mesa Verde National Park in 1906 was abetted by archaeological reporting practices that supported a similar disconnection of the site from recent history in order to assert its status as a reified embodiment of a generalized notion of prehistory, as that notion was understood at the time.3 Just as many contemporary conflicts over historical connections stem from NAGPRA-mandated protocols, here too the cultivation of a new and distinct notion of prehistory was tied to legislation, the Antiquities Act, which was passed in the same year, 1906, as the founding of the park. However, while NAGPRA facilitates, however imperfectly, the repatriation of ancient indigenous sites and artifacts, the Antiquities Act identified them as common national property to the extent that they were deemed prehistoric. The consolidation of archaeological sites like Mesa Verde as national parks, and by extension as constitutive elements of a specifically national cultural heritage, thus hinged on the anachronistic framing of the indigenous cultures they displayed, not as a modern feature out of place in a past setting, but, conversely, as a site from which recent history has been removed.4

This essay considers this temporal and cultural operation tied to the production and display of knowledge about a physical place from the standpoints of both its historical emergence within archaeological practice as it evolved as a discipline in the U.S. and the specific textual and pictorial mechanisms that support it in archaeological reports devoted to the site, focusing in particular Jesse Walter Fewkes’s Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park (1909 & 1911).5 First, earlier archaeological writing devoted to the Southwest tended to assert a connection between Ancestral Puebloan ruins and existing Pueblo communities, even if such a connection was presented as a decline in cultural accomplishment, an orientation that is most visibly reinforced by the consistent picturesque framing of ruins in these reports’ illustrations. In contrast, Fewkes more forcefully isolates and defines a pristine prehistoric type embodied in the Mesa Verde remains. That is to say, previous writers stressed a dynamic of cultural decline, while Fewkes works towards the creation/preservation of an archaic cultural entity disengaged from existing indigenous groups, an orientation perhaps best exemplified in his notion of a “type ruin,” in which actual structures at various Mesa Verde locales take on the character of exemplary cultural emblems. Second, in cultivating the perception of Mesa Verde as a historically-disconnected, prehistoric site, Fewkes’s report differs from its forerunners in several aspects of both its textual and pictorial presentation of archaeological data. The key textual and pictorial differences examined here include the consolidation of distinct structures (namely, how many there are and which are noteworthy), an emphasis on descriptive as opposed to analytical modes of writing, and finally the cultivation of a photographic aesthetic that bolsters the sense of a timeless ruin and which stands in marked contrast to the more picturesque modes of depicting ruins utilized more commonly in the previous century.

The kind of anachronism enacted in Fewkes’s presentation of Mesa Verde bears some similarities to a re-thinking of anachronism in art historical scholarship of the past decade, in particular the notion of “anachrony” as developed in Alexander Nagel and Christopher Wood’s Anachronic Renaissance (2010).6 Nagel and Wood investigate how Renaissance writers employ both historical/chronological and “anachronic” models of time in discussing past and contemporary art, models of time which are notably in tension. The former is bound up with developing conceptions of individual authorship (“the authorial performance cuts time into before and after”), while the latter relies on a substitutional logic in order to legitimate the authenticity of artifacts that reinforce a sense of community.7 In particular, the substitutional logic of the anachronic perspective enables the conservation of identity despite the history of an artifact’s use and alteration over time; for example, in identifying older buildings as “antique,” Renaissance writers documenting the historic structures of cities (those structures that attested to a city’s origins and, hence, to the overall identity of the city itself) “left unresolved – deliberately unresolved – the distinctions between being an old building, replacing an earlier building, and altering an earlier building”( Nagel and Wood 2010, 136). Fewkes’s presentation of Mesa Verde would seem to follow this anachronic substitutional logic, then, especially in describing/displaying the structures of Mesa Verde as “type ruins” (not “antique” but a Southwestern indigenous prehistoric “type,” in which the manifold activities of excavation and restoration of structures work to secure that identity).

Even more, the nascent conditions of an historical framing of past art that Nagel and Wood connect with Renaissance writers’ variable engagement of an anachronic perspective bears some resemblance to the first stages of historical inquiry into ancient indigenous societies in North America. Simply put, such writers make errors:

Whereas the age of a building had once been unspecified, even unquestioned, now at the moment of philology and historical taxonomizing [in the Renaissance], scholars began to interrogate the typological, substitutional identities of buildings, but without adequate preparation. The antiquarian “fell into careless habits of accuracy.” (Nagel and Wood 2010, 138)

As discussed below, Fewkes’s work is a culmination of the “descriptive/classificatory” phase of American archaeology, seemingly paralleling the early “taxonomizing” interests of Renaissance antiquarians. As Nagel and Wood describe it, the “careless habits of accuracy” accompanying the development of a historical/chronological perspective are not just the result of inadequate or faulty methodologies (involving stylistic analysis of architecture or correlation of written records with specific structures), but the desire to define the present, the specific city in question, in relation to an originary past, motivating the continued employment of the anachronic perspective. The key differences in Fewkes’s project, then, are twofold: instead of grounding an urban identity in “antiquity,” he contributes to a sense of national identity by isolating and preserving, and thereby creating, American “prehistory.”

Nineteenth-Century Archaeology, Picturesque Aesthetics, and Conceptions of Cultural Continuity and Decline

The territorial expansion of the U.S. over the course of the nineteenth century was most often accompanied by the forced removal of Native American tribes from areas that were desired for settlement. This process was abetted by the widespread notion of Native American cultural inferiority, in particular as reflected in the absence of substantial, permanent native architecture. With the acquisition of the Southwest in the aftermath of the U.S.-Mexican War (1846-1848), however, it became clear that cultural inferiority would be more difficult to argue on those grounds, as numerous sites like Mesa Verde pointed to an extended history of more impressive indigenous architectural achievement. Many of these architecturally impressive ruins – Mesa Verde, Chaco Canyon, and Frijoles Canyon, the latter two in New Mexico – were built during a period of population expansion and intense construction activity in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries by Ancestral Puebloans, who subsequently relocated to other areas closer to the Rio Grande from the thirteenth century on.8 They roughly lie along the northern perimeter of the extent of Ancestral Puebloan occupation and were consequently more vulnerable to extended periods of drought.9

The first proto-archaeological investigations of these sites, beginning at midcentury, consistently acknowledge the scale and sophistication of their architectural remains.10 Although John Russell Bartlett’s account of the U.S.-Mexican Boundary Survey (1854) is ostensibly intended to document survey activities and to assay the agricultural and mining potential of territory acquired in the aftermath of the U.S.-Mexican War, it devotes a disproportionate amount of space to describing and speculating about native ruins, especially as they become more numerous in the latter phases of the expedition. At certain points it even seems as though the entire landscape is one vast expanse of toppled structures: “From the summit of the principal heap [or ruin] … there may be seen in all directions similar heaps” and “In every direction as far as the eye can reach are seen heaps of ruined edifices.” (Bartlett 1854, 247, 275)11. Typically these early writers contrast the magnificence of such native ruins with contemporary indigenous dwellings, implicitly or explicitly arguing for some notion of cultural deterioration or stagnation to conform with pre-existing biases towards Native Americans. For example, William H. Holmes, who investigated Ancestral Puebloan ruins on the Mancos River, near Mesa Verde, two decades later as part of a government-sponsored mapping survey, writes that “there is bountiful evidence that at one time [the Mancos River] supported a numerous population … a race totally distinct from the nomadic savages who hold it now, and in every way superior to them.” (Holmes 1876, 3) Characteristically, Holmes equates the size of ruins with a sense of both cultural accomplishment and its antiquity:

In one place in particular, a picturesque outstanding promontory has been full of dwellings, literally honeycombed by this earth-burrowing race, and as one from below views the ragged, window-pierced crags, he is unconsciously led to wonder if they are not the ruins of some ancient castle, behind whose moldering walls are hidden the dread secrets of a long-forgotten people. (Holmes 1876, 37)

As with Bartlett, he too is frequently impressed with the sheer scale or extent of built remains, but he more often associates such vastness with the magnitude of history separating original inhabitants from present-day Native Americans.

As suggested by Holmes’s emphasis on the “picturesque” (“in particular,” while the word “outstanding” refers both to the actual shape of the promontory and its exceptional noteworthiness), it is striking how often the illustrations of ruins in these early reports adopt some version of the picturesque view common in European landscape paintings and prints. In Bartlett’s expedition report, his illustration of Casas Grandes in Chihuahua situates the ruin in its environment in a fashion similar to Thomas Cole, the American landscape painter who pioneered the adaptation of European picturesque conventions in the U.S., as in his Roman Campagna of a decade earlier (figures 3 & 4).12 In both images, the artist amplifies the perception of age by emphasizing the jagged contour of the ruin, implying its active deterioration and eventual return to natural as opposed to manmade forms.13 Similar, too, is the inclusion of present-day spectators in the foreground (a shepherd in Cole’s painting, local rancheros in Bartlett’s illustration), who are clearly detached from the historical period suggested by the ruin. Bartlett was not the accomplished painter that Cole was and his illustrations contain abbreviated or less nuanced versions of the picturesque devices employed by Cole. The shepherd’s ignorance of the significance of the classical ruins among which his sheep are dispersed is thematically related to the question of how attentive he is to his flock, while Bartlett’s rancheros simply gesticulate towards the remains of Casas Grandes. Especially missing in Bartlett’s illustration is Cole’s measured treatment of staffage figures to guide the viewer’s eye from foreground to background, which not only takes time (and consequently evokes the passage of time that is the painting’s subject), but also more strongly activates a parallel between landscape and history, foreground to background versus present to past. Still, it is clear that Bartlett derives many of the ways his illustration conveys temporal meaning from a fundamentally picturesque template.

Figure 3. John Russell Bartlett, “Ruin at Casas Grandes, Chihuahua,” in John Russell Bartlett, Personal Narrative, vol. 2 (1854).

Figure 4. Thomas Cole, Roman Campagna (1843).

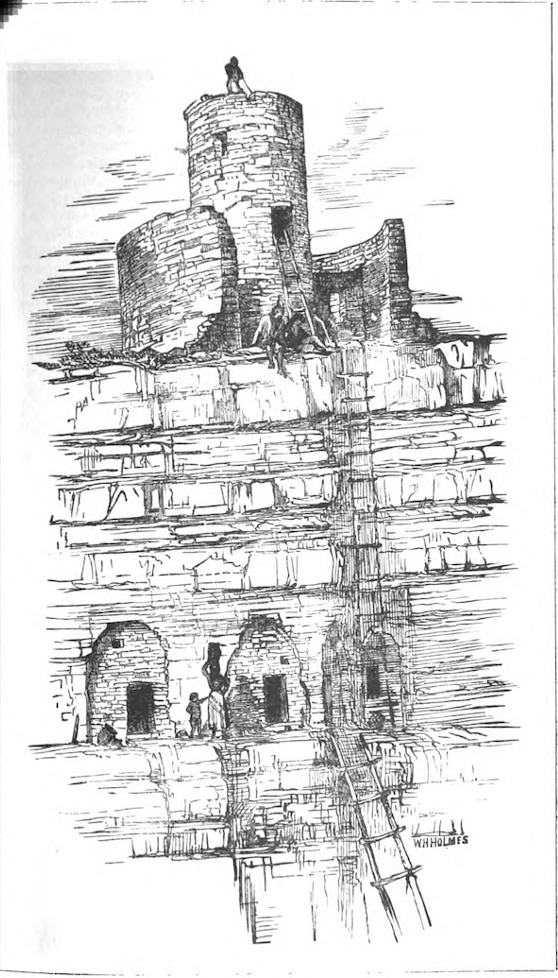

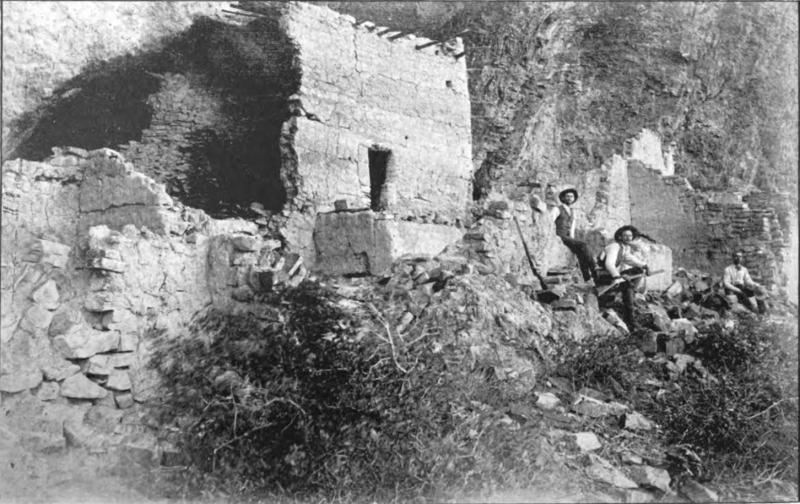

Publications from later in the century, such as Holmes’s report or Adolph Bandelier’s more professionalized work on Ancestral Puebloan sites in New Mexico (Bandelier conducted fieldwork under the auspices of the Archaeological Institute of America), contain fewer scenes that so closely follow this picturesque model. In part this difference is a result of the proliferation of other kinds of images within these reports (diagrams, charts, and maps).14 An additional factor is that later illustrations that do present some kind of ruin in a landscape are more frequently based on photographs (which opened up other kinds of pictorial intervention).15 Even so, the picturesque model continued to exert some influence and often in unexpected ways. A depiction of a ruin on the San Juan River in Holmes’s report is intended to present a reconstruction of the structure’s original appearance at the time it was built (figure 5). It deviates sharply from the distanced view featured in Bartlett’s and Cole’s landscape images and it naturally lacks the disconnected modern observer, but the artist has chosen to retain the chipped stone and broken outline of the ruin as it appeared in the present. A photographic example from Bandelier’s Final Report of Investigations among the Indians of the Southwestern United States (1892) also lacks the distanced view and its human figures are principally included to indicate scale and to attest to or authenticate the presence of Bandelier and his team at the site, supplementing or paralleling the implied presence of the photographer (figure 6) (Bandelier 1892).16

Figure 5. Plate 3, in William H. Holmes, “A Notice of the Ruins of Southwestern Colorado,” Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, vol. 2 (1876).

Figure 6. Charles Lummis, “Cave Dwellings on the Upper Rio Salado, Arizona,” in Adolph Bandelier, Final Report of Investigations among the Indians of the Southwestern United States, vol. 2 (1892).

Overall, these first investigations of Ancestral Puebloan sites tended to argue for some notion of cultural deterioration or stagnation and the picturesque view reinforced that perspective. Most commonly, the imputation of cultural stagnation is based on a general assessment of architectural sophistication or its lack, as in Holmes’s evocation of “a race totally distinct from the nomadic savages who hold [the Mancos River] now, and in every way superior to them.” For his part, Bartlett at least initially blames an exploitative Mexican colonial regime for what he sees as a decline in quality in ancient versus present-day indigenous dwellings. Bandelier offers a contrary point of view, based in part on his review of Spanish-language colonial documents (which may have presented missionary activities in a more positive light), claiming that colonial government and Franciscan and Jesuit missionary activity had tangible benefits in introducing different aspects of civilization (concepts of land ownership, agricultural practices, and, most important for Bandelier, Christian religious devotion). More specifically, their absence in the aftermath of the U.S.-Mexican War is seen as a negative development: “The effects of education, or instruction, have … now well-nigh disappeared and there are many and very plain tokens of a relapse into barbarism.” (Bandelier 1883, 220). Despite these various ways of accounting for cultural stagnation, however, to the degree that the picturesque ruin conveys a sense of long eclipsed grandeur, asserting a historical connection with contemporary native peoples both reflects poorly on their existing habitations and helps to absolve the American viewer of any responsibility for that discrepancy. Looking ahead to the photographic illustrations of ruins at Mesa Verde in Fewkes’s reports, such an emphasis on cultural stagnation may be disparaging, but it nonetheless affirms a historical connection that is minimized by the non-picturesque format of the Fewkes illustrations.

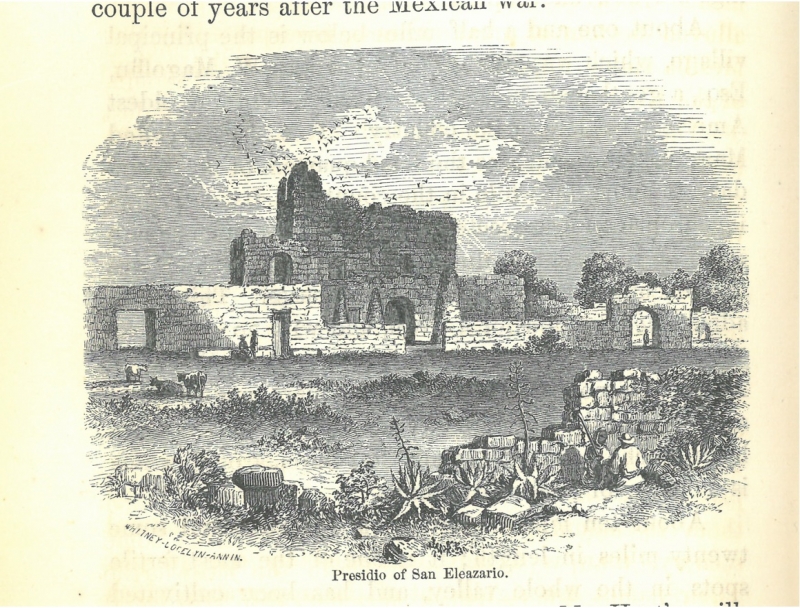

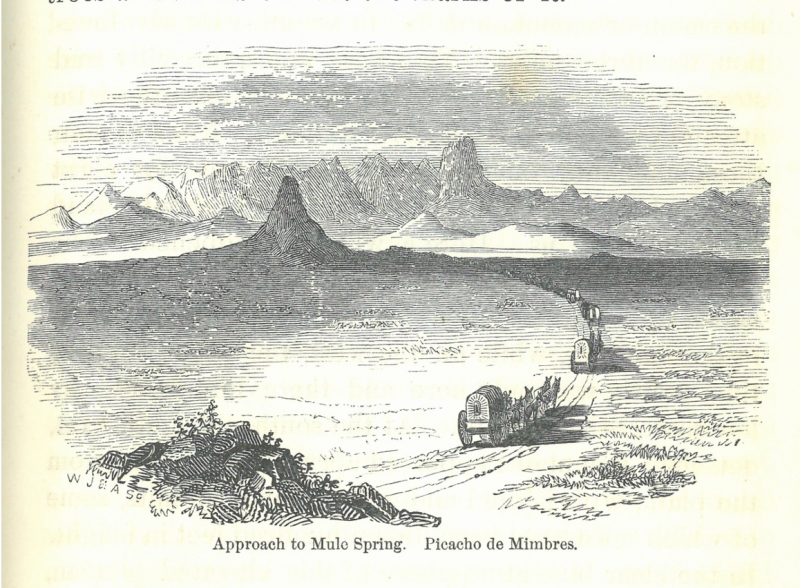

Before turning to Fewkes’s work at Mesa Verde, it is instructive to see how deviating from picturesque conventions in the earlier reports can affect the perception of time and complicity in the effects of colonialism. Bartlett’s account of the Boundary Survey is initially optimistic about the prospects for integrating the Southwest and its peoples, both Native American and Mexican, within an American nation he sees as experiencing unprecedented economic and cultural growth. Many of the towns and villages he encounters at the beginning of the survey are visibly scarred from the recent conflict between the U.S. and Mexico and the picturesque depiction of these “ruins,” such as the Presidio of San Eleazario, confers an aura of antiquity that implies that the aftermath of war is a thing of the past (figure 7). As his survey proceeds, however, he becomes more and more aware of the chaos of that post-war environment and numerous illustrations in the later sections of his report noticeably exaggerate elements of the picturesque view in a manner that suggests that the environment of the Southwest itself somehow accelerates the historical process, rapidly reducing any attempt at civilization to rubble.17 In a depiction of the “Approach to Mule Spring,” the perception of distance and the pull from foreground to background is much sharper than in the depictions of Casas Grandes or San Eleazario; the lines of wagons and troops diminish rapidly, as if the survey were being swallowed up by the landscape (figure 8). Rather than confirming some notion of American exceptionalism, the illustration echoes Bartlett’s increasing cynicism by implying that the harsh environment of the Southwest will consume the expedition just as it did its previous occupants.

Figure 7. Henry C. Pratt, “Presidio of San Eleazario,” in John Russell Bartlett, Personal Narrative, vol. 1 (1854).

Figure 8. Henry C. Pratt, “Approach to Mule Spring. Picacho de Mimbres,” in John Russell Bartlett, Personal Narrative, vol. 1 (1854).

Fixing the Past in Mesa Verde as a “Type Ruin”

Fewkes conducted excavations and oversaw restoration work at numerous sites at Mesa Verde, in the period 1908-1922, as directed by the Secretary of the Interior (initially James Rudolph Garfield, the son of the President) and under the auspices of the Bureau of American Ethnology.18 Many of the ruins at Mesa Verde had been previously visited by both amateurs and professionals, first “discovered” by the Wetherell family, the ranchers who owned the land, later popularized by the journalist Frederick Chapin, who visited the site in 1889 and 1890, and then examined by the Swedish scholar Gustaf Nordenskiöld in the same period, whose 1893 Cliff Dwellers of the Mesa Verde represents the first scientific survey of the ruins (Nordenskiöld 1893). Nordenskiöld’s earlier publication informs Fewkes’s approach in a number of ways: he is quoted extensively in introductory sections, his initial survey identified the principal locations covered by Fewkes, and, less positively, his plentiful collecting of artifacts in part motivated the Antiquities Act to prevent further removal of artifacts.19 Indeed the initial wording of the Antiquities Act specifies that “The President may … declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric objects, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated on land owned or controlled by the Federal Government to be national monuments.”20 Within this formulation, the basis for national monument status for Mesa Verde, that it was not private land from which objects could be removed, resided in its being prehistoric (and having scientific interest).

However, while Nordenskiöld’s publication is influential, he avoids designating any ruin or artifact as “prehistoric” per se, preferring instead to identify them as generically “ancient.” The reports on the Mesa Verde ruins by Fewkes presents a markedly different perspective on Native American history, brought about in large part by the introduction of “prehistory” as a defining temporal concept demarcating the object of archaeological investigation, as the discipline became more professionalized over the course of the nineteenth century. The British writer John Lubbock is usually credited with introducing this notion in 1865 with his treatise Prehistoric Times as Illustrated by Ancient Remains and the Manners and Customs of Modern Savages, including, more problematically, the notion that existing, “primitive” cultures could be compared with ancient ones. Lubbock’s ideas in turn were popularized in the U.S. by Lewis Henry Morgan (Bandelier’s mentor), who also developed an evolutionary model of successive stages of social complexity. Fewkes does not employ Morgan’s value-laden terminology (“savage,” “barbaric,” “civilized,” labels used extensively by Bandelier and others in the second half of the nineteenth century), although he does make cultural comparisons on the basis of the perceived quality of workmanship and the perceived sophistication of manufacturing and agricultural techniques, so that cultures are similarly, if more subtly, “ranked.”21 What is notable about his work is the avoidance of the more chronologically informed conceptions of prehistory that were being developed in recent European archaeology, an avoidance that serves to accentuate the staging of Mesa Verde as a historically-disconnected, prehistoric site in order to constitute it as part of the nation’s cultural patrimony.

Historiographic studies of American archaeology have long recognized its hesitancy to adopt the increasingly chronologically-differentiated notion of prehistory emerging in European scholarship in the second of the nineteenth century, namely the identification of Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic time periods primarily tied to innovations in tool-making and supported by stratigraphic archaeological finds. Instead,

at the beginning of the 20th century there was no good evidence that the American aborigines had been in this hemisphere for any appreciable length of time [and] there was no good support for significant or major culture change within the archaeological evidence that pertained to the Indians and their ancestors. (Willey and Sabloff, 87)22

In “Division and Discord of Prehistoric Chronologies,” François Bon explores various motivations or “factors” underlying the European elaboration of a more nuanced prehistoric chronology, focusing on key French theorists such as Gabriel de Mortillet and Henri Breuil (Bon 2018, 76). One shift that Bon traces which is especially relevant here is from an earlier evolutionary perspective, epitomized by Mortillet (which denied the humanity of Paleolithic societies on the basis of their being supposedly incapable of cultural achievement), to one that pushed back human identity into earlier time periods and instead focused on discovering the origins of basic cultural patterns understood to structure both past and present human societies.23 In contrast, Fewkes’s prehistory has no chronological component, neither divided into Paleolithic, Mesolithic, or Neolithic horizons (what would be, in a sense, proto-historical, as having a definite before-and-after sequence) nor linked to historical time (whether in the colonial or national periods or more recently). Although Fewkes employs the term extensively throughout his reports it is never formally defined.24 But whereas Nordenskiöld’s use of “ancient” is nonspecific and can refer to both older and more recent points in time, several differences in textual and pictorial practices have the effect in Fewkes’s report of portraying the Mesa Verde as an almost monolithic emblem of American prehistory.

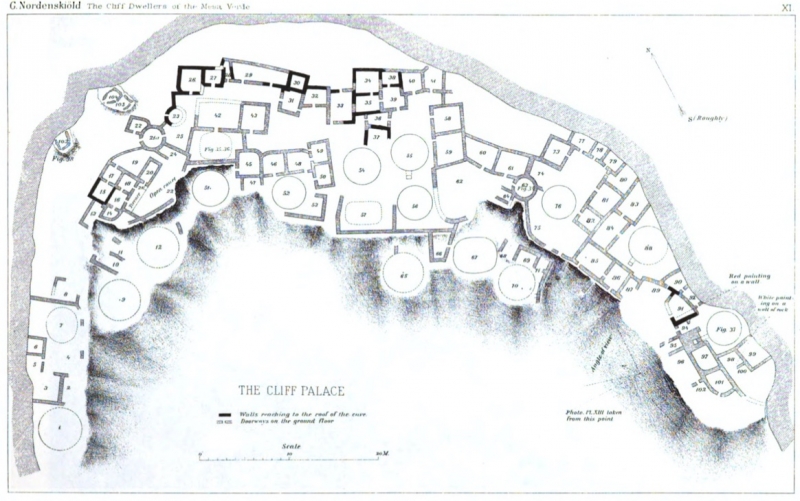

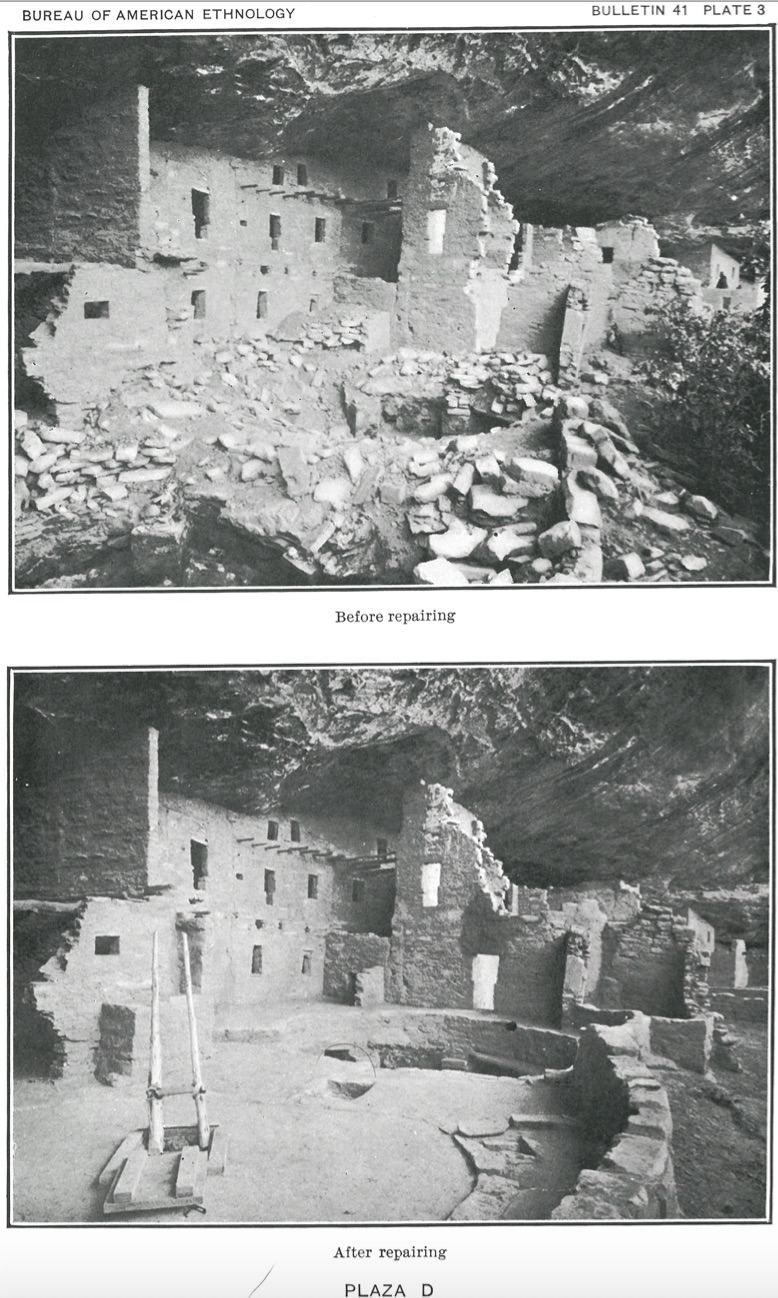

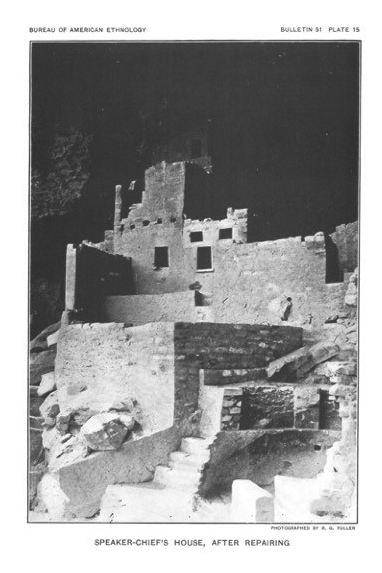

The first key difference in the reports’ presentation of the Mesa Verde ruins is the greater definition given to distinct structures within the different Ancestral Puebloan sites in the area, both in terms of the physical structures themselves and their depiction in maps and illustrations. Part of the reason for this difference is that Nordenskiöld was the first professional to visit Mesa Verde and conducted the initial series of systematic excavations and map drawings of key locations such as the Cliff Palace and Spruce-Tree House. However, the greater definition given to distinct structures by Fewkes also corresponds with giving them a permanent form as elements within a prehistoric display that will remain unchanged for all time, with neither existing buildings further restored nor additional buildings added in the future.25 Fewkes’s work establishes an archaeological ground zero, as reflected in a comparison of the authors’ maps of the Cliff Palace (figures 9 & 10). The speculative dotted lines and undifferentiated blank spaces of Nordenskiöld’s map have been replaced by more numerous and sharply defined spaces (note especially the multiplication of circular kivas, traditionally male ceremonial spaces, the demarcation of zones or “quarters,” and the labeling of distinct terraces). Many of the photographic illustrations in Fewkes’s report also pointedly show the difference between “before repairing” and “after repairing” the structures (figure 11).

Figure 9. “The Cliff Palace,” in Gustaf Nordenskiöld, Cliff-Dwellers of the Mesa Verde (1893).

Figure 10. “Cliff Palace,” in Jesse Walter Fewkes, Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park (1911).

Figure 11. Jesse Nusbaum, “Before Repairing” and “After Repairing” (Plaza D, Spruce-Tree House), in Jesse Walter Fewkes, Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park (1909).

In keeping with the effort to present a definitive and unchanging example of a prehistoric settlement, Fewkes also extends or amplifies the static descriptive writing style found in Nordenskiöld’s report. Both reports devote considerable space to straightforward description of various structures, but Nordenskiöld more consistently attempts to link patterns in architectural style and designs in pottery and textiles to comparable examples from past and current Puebloan cultures. A particular focus for Nordenskiöld is linking the stepped forms of decorative basketweaves and ceramic border designs. In contrast, as stated by the Letter of Transmittal introducing Fewkes’s report on the Spruce-Tree House, its key contribution is that it contains “the most important descriptions” of the Spruce-Tree House, specifically of what he calls “the requirements of a ‘type ruin,’” namely the baseline example of Ancestral Puebloan architecture (Fewkes 1909, iii). In the second report he goes further; the title of the first subsection after the “Introduction” is “Cliff Palace a Type of Prehistoric Culture,” in which he writes that

Considering ethnology, or culture history, as the comparative study of mental productions of groups of men in different epochs, and cultural archaeology as a study of those objects belonging to a time antedating recorded history, there has been sought in Cliff Palace one type of prehistoric American culture … The condition of culture here brought to light is in part a result of experiences transmitted from one generation to another, but while this heritage of culture is due to environment, intensified by each transmission, there are likewise in it survivals of the culture due to antecedent environments, which have also been preserved by heredity, but has diminished in proportion, pari passu, as the epoch in which they originated is further and further removed in time. (Fewkes 1911, 11)

Thus, although he acknowledges micro-changes over time (“one generation to another”) and even cultural features deriving from before the occupation of Mesa Verde (“survivals of the culture due to antecedent environments”), the emphasis is on a coherent, environmentally-conditioned cultural type identified as prehistoric and with a static form, the Cliff Palace, as if to describe the Cliff Palace is to describe the culture.

Fewkes enumerates various artifactual remains, but he concentrates on architecture, both because most portable artifacts have already been removed from the site and because architecture by itself is more easily maintained and monitored. Before taking on the supervision of exploration and restoration activities at Mesa Verde, Fewkes was known primarily for documenting Hopi ceremonial activities. His familiarity with Hopi religion and specifically Hopi architectural forms associated with religious practice guides his investigation of various Mesa Verde structures, but Hopi parallels are given in a purely descriptive mode, as if to clarify appearance alone and not to suggest cultural affinity.26 In his first report he notes that “Wherever roofs still remain they are found to be well-constructed and to resemble those of the old Hopi houses,” but this comparison is not developed any further (Fewkes 1909, 10). Similarly, in the same report he writes that “The other important opening in the [kiva] floor is one called the sipapû, or symbolic opening into the underworld … A similar symbolic opening occurs in modern Hopi kivas” without drawing any conclusions (Fewkes 1909, 18).27 The overall impression is of structures with a variety of features, some of which happen to resemble Hopi architectural components. Moreover, while he does compare the stylistic traits of Mesa Verde buildings to contemporary Hopi architecture, it is principally to emphasize the site’s disconnection from nearby Ute tribes and to maintain the superiority of Ancestral Puebloan design and masonry technique, as if later modifications were deviations from a standard. Indeed, whereas both Chapin and Nordenskiöld consider current Ute attitudes toward and use of Mesa Verde sites, Fewkes’s reports in their more purely physical descriptive orientation minimize any such discussion.

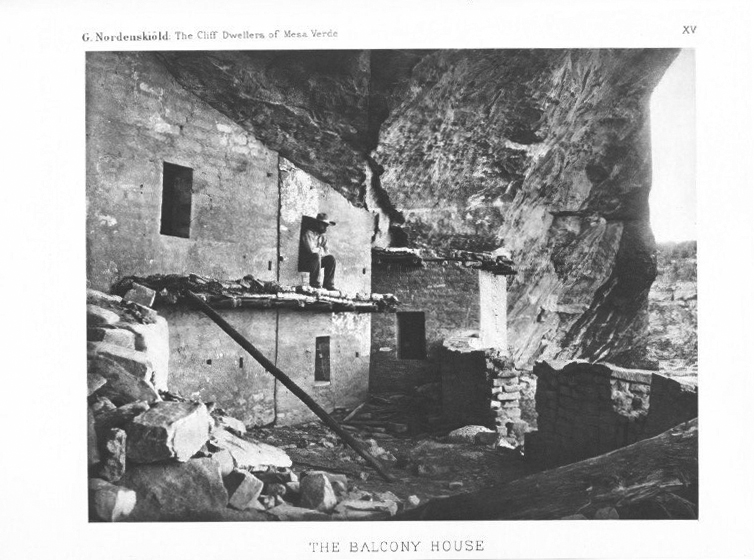

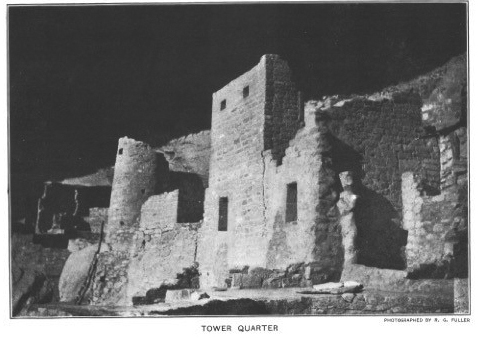

Finally, though, the intention to present a national treasure and not a historically and culturally contingent, lived environment is most evident in the photographic aesthetic of the timeless ruin utilized throughout Fewkes’s Mesa Verde publications. First, while Nordenskiöld’s report is also generously illustrated with views of Mesa Verde ruins, they are notable for their inclusion of human figures, as in the picturesque landscape views found in earlier writings about Ancestral Puebloan sites (figures 12). Not only do these figures give a sense of scale, they historicize the moment of the photographs’ creation as well as revealing their outsider status (they are members of Nordenskiöld’s investigating team) as they awkwardly navigate or inhabit these spaces. Nordenskiöld is also more apt to show the ruin as part of the larger landscape, a further hold-over from the picturesque view, whereas the views given Fewkes’s reports are either of single structures or groups of structures or the now-familiar tableau-like ruin ensconced and isolated underneath its sheltering cliff overhang (figures 13-15). Scholarship on the role of nineteenth-century photography in shaping the image of classical antiquity has noted how both tourist and more professional archaeological photographers employed a tighter field of view and a consistent viewpoint to isolate and shape an increasingly familiar image of famous monuments, removing signs of more recent construction in a manner that disconnects the monument from the living city in which it happens to be located (Holliday 2005, Papadopoulos 2006). The photographs of ruins in Fewkes’s reports perform a similar function and, moreover, their perspective corresponds with the views that would be encountered by tourists on the pathways that were also a component of Fewkes’s restoration work. Most of all, the photographs capture the meticulously repaired surfaces, evident as larger expanses of unmodulated tone compared to the more uneven and mottled textures of Nordenskiöld’s photographs, in which the given structure assumes its permanent form, both an evident ruin and oddly “cleaned up,” no longer exhibiting the hallmarks of encroaching decay that was emphasized in the picturesque view.

Figure 12. Balcony House (Chapin’s Mesa), in Gustaf Nordenskiöld, Cliff-Dwellers of the Mesa Verde (1893).

Figure 13. Spruce-Tree House from the Mesa, in Gustaf Nordenskiöld, Cliff-Dwellers of the Mesa Verde (1893).

Figure 14. R.G. Fuller, “Tower Quarter” (Cliff Palace), in Jesse Walter Fewkes, Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park (1911).

Figure 15. R.G. Fuller, “Speaker-Chief’s House” (Rooms 71-74, Cliff Palace), in Jesse Walter Fewkes, Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park (1911).

The generalized notion of prehistory utilized in Fewkes’s reports would not persist in later American archaeology. Already in these first decades of the twentieth-century scholars were beginning to adapt a more chronologically differentiated notion of prehistory to North American sites. Franz Boas is a key figure here; among other contributions, he oversaw the Jesup North Pacific Expedition (1897-1902), which provided support for the existence of the Bering land bridge and a much vaster timescale for human occupation of the continent. Fewkes participated in these shifts as well, giving shape to the direction of archaeological research generally in his capacity as director of the Bureau of American Ethnology. As this essay has tried to show, to a certain extent it is the requirements of a permanent national monument that are especially well served by an undifferentiated and monolithic notion of prehistoric time. Just as the Renaissance writers discussed by Nagel and Wood ignored the signs of past and recent alteration of artwork in favor of an ancient status that helped underwrite a sense of urban identity, so Mesa Verde, as presented by Fewkes, testifies to an antiquity preceding and thereby anchoring national identity while also drawing attention away from continuing inequities in more recent relations between the federal government and native populations. Whereas as late as Nordenskiöld’s time the Cliff Palace was visited and utilized by both ranchers and members of the local Ute tribe, as a national monument the site will evidently no longer register the effects of ongoing history.