Introduction

A number of events have been interpreted as “political crises” in the UK over the last decades. The British Political Tradition itself for instance, which rests on the principle of Westminster’s sovereignty and on a hierarchical and centralised organization of power (Hall 2011), has been challenged by the devolution settlement. Separatist parties have also gained momentum in Scotland and Northern Ireland, raising the question of a crisis of unionism and Britishness. Similarly, the Brexit referendum has been labelled as an unprecedented crisis in British contemporary history (Schnapper and Avril 2019). Traditional and once dominant parties themselves have seen their membership rates drop and voters’ confidence diminish. These elements all point to a broader political crisis at the UK level which calls for definition and analysis.

Northern Ireland has also experienced a number of crises since the beginning of the peace process. The Assembly has been suspended on numerous occasions. Besides, since February 2022 the Northern Ireland Assembly has been suspended for the third time since the signing of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement. The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) resigned in protest of the Northern Ireland Protocol. Following the election of May 5th 2022 which saw Sinn Féin get the largest amount of seats for the very first time in Northern Irish history, the main unionist party has refused to appoint a Deputy First Minister, leading to another prolonged suspension of the Assembly. This stalemate confirms the idea that this territory is going through yet another political crisis. This crisis concerns unionist parties more specifically but it may also signal a crisis of unionism as a political ideology. Northern Irish unionist parties have failed to attract new voters, to convince new members to join their ranks and their electoral results have been disappointing in the latest election, although put together they still won more seats than nationalist parties in 2022. However, this idea of a unionist crisis is not a recent phenomenon and its very nature calls for definition as regards its duration, its scope and the parties’ ability to reform and adjust to new sets of circumstances. The notion of crisis itself is debated; some commentators do not believe that the challenges faced by unionism constitute a “crisis”. Arthur Aughey who wrote extensively on Northern Irish unionism refuted the idea that unionism experienced an “identity crisis” in Under Siege: Ulster Unionism and the Anglo-Irish Agreement (1989) for example. He dismissed the idea of a unionist “identity crisis” for he believed that unionism should not be seen as a cultural or an ethnic concept but on the contrary as a rational one based on citizenship. Norman Porter qualified this idea in Rethinking Unionism, An Alternative Vision for Northern Ireland (1996). In this book published a couple of years before the Belfast / Good Friday Agreement, he identified a number of challenges for Northern Irish unionism but he refused to have a say in the debate whether they constituted indeed a “crisis of unionism”. He wrote:

The present circumstances of unionism are constituted in large measure by three sorts of challenges unionists cannot hope to avoid indefinitely: those internal to unionism, those originating beyond the borders of Northern Ireland, and those located within its borders. Whether the cumulative effect of these challenges, justifies the conclusion that unionism is in a state of crisis is a contentious point. Talk of a crisis of unionism, especially an identity crisis, is fashionable in some circles but hotly contested in others. (Porter 1996: 25)

The 2022 elections deepened what Porter called the “internal challenge” to unionism, the fragmentation between the different unionist parties and what seems to be the increasing gap between the unionist electorate and the political elite.

Are these poor electoral results the sign of a crisis of support due to an increasing gap between the leadership and their electorate or rather the sign of a short-term disaffection? Or are Northern Irish unionist parties experiencing a deeper ideological crisis as regards the meaning of unionism in the 21st century?

The phrase « unionist ideology » also calls for definition. However, interpretations vary and it would be too reductive to give a fixed definition of what unionist ideology or ideologies might represent. As explained by Feargal Cochrane in Unionist Politics and the Politics of Unionism since the Anglo-Irish Agreement (1997):

Unionist ideology contains diverse interest groups with little in common other than a commitment to the link with Britain. While this position remains relatively cohesive during periods of constitutional crisis when they can articulate what they do not want (namely a weakening of the link with Britain), the coherence of the ideology begins to disintegrate when unionists are forced to establish a consensus for political progress. (Cochrane 1997: 35)

Jennifer Todd (2020) also described this political ideology as an “umbrella organisation”, home to two main groups with competing agendas - Ulster loyalism and the Ulster British tradition - which were not able to promote a positive vision of this ideology.

Along the same line, Colin Coulter wrote:

[Unionism] does not possess a single essence, but rather exists as a complex formation that accommodates a number of divergent and contradictory ideological impulses and political interests sharing little in common save for a commitment to the Union itself. The ideological persona of unionism is shaped by philosophical currents that are variously liberal and reactionary, secular and sectarian. (Coulter, 1994: 7)

Therefore, the variety of “unionisms” is also reflected in the positioning of the different unionist parties, which will be the focus of this paper.

This article will therefore dwell on the idea of political crisis for Northern Irish unionist parties, in terms of electoral results but also in terms of a seemingly growing disaffection between voters and the parties’ leadership, suggesting that unionism might be at a crossroads following the 2022 election. Indeed, the rise of a non-aligned group and the fact that the unionists came only second in the election are recent phenomena that constitute new challenges for the pro-Union camp.

Paul Gillepsie defines a crisis as follows:

[Crises are] historical moments of surprise, quickening of time and change, decision and choice. They are turning points that disrupt established orders, goals and expectations, driving leaders to respond defensively or by innovation to protect or extend regimes. (Gillepsie 2020: 510)

The 2022 election has indeed been described as “historical” and “seismic” as said above. It remains to be seen whether or not political leaders are able to achieve a new unionist “vision” in a post-devolution and post-Brexit context in Northern Ireland. Unionism as a political ideology has also distinct variations in this territory. Therefore, this paper will seek to explore the nature and the ramifications of the crisis within political unionism in Northern Ireland. It will focus on the current electoral trends and the persisting fragmentation of the unionist vote. Comparing Northern Ireland to another UK territory is problematic since Ulster has its own political and party system and it has a different devolution settlement.1 However, this paper will also touch on the broader crisis within British unionism. Indeed, the core aspect of Unionism is about connection and exchange and the last part of this paper will be devoted to recent endeavours at the UK level to define positively the unionist ideology and reunite the diverse and plural unionist trends.

This paper will first analyse the results of the Northern Ireland Assembly election of 2022, exploring the topic of an electoral crisis for unionist parties. It will go on to question the underlying trends behind these results in terms of party membership and voters’ adherence to the unionist project. Then, the third part will be dedicated to the Northern Irish Protocol as a potential factor for a deeper crisis in the region, and will question the issue of “vote polarisation” in Northern Ireland in light of recent electoral trends. Finally, the focus will be placed on the attempts at creating a “connected Unionism” beyond party politics at the UK level to solve the crisis of unionism and Britishness.

1. Election results in Northern Ireland: an electoral crisis within unionism?

The crisis unionist parties have been going through in Northern Ireland finds its roots in a number of causes. Indeed, although all unionist parties officially oppose the Northern Ireland Protocol, they have adopted different stances on the issue, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) being first in favour of reforming the text for instance. These discrepancies reveal a deeper issue at stake for unionist parties, the competition for traditional unionist voters’ first preference vote.

1.1 The 2022 Northern Ireland Assembly election: results and vote transfers

The 2022 Assembly election has been described as seismic, as an epochal change by many commentators and journalists.2 Indeed, for the very first time, Sinn Féin had outflanked the DUP, winning 27 seats and the highest share of first preference vote. The party was then in the position of appointing a nationalist First Minister. The DUP came second with 25 seats, the UUP came fourth with 9 seats and the TUV won just one. In addition, two independent unionists were also elected, Alex Easton for North Down and Claire Sugden for East Londonderry.

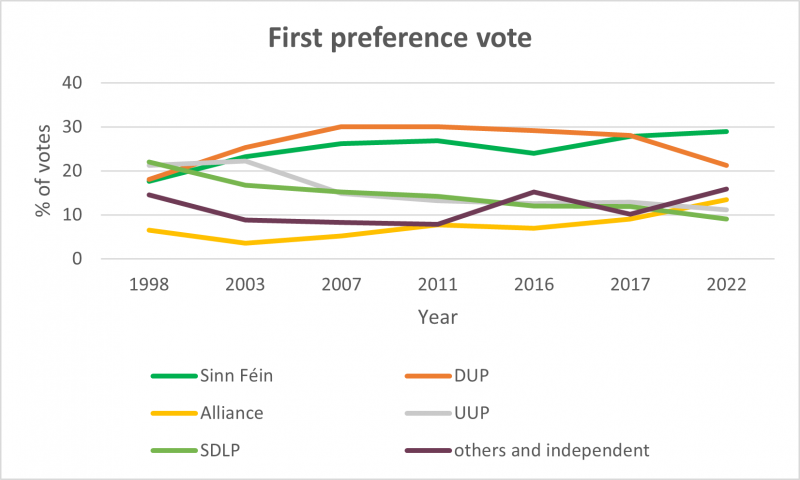

It appears that the vote share of the DUP had been declining since 2017. It went up to 35.2% in 2011 and 2016 and dropped to 31.1% in 2017 and 27.8% in 2022. In addition, the number of first preference votes significantly decreased between 2017 (28.1%) and 2022 (21.3%). The DUP remains the largest unionist party, yet both the DUP and the UUP saw their first preference votes reduce in these elections, while Sinn Féin and Alliance gained more first preference votes. Moreover, first preference vote for the TUV more than tripled.

First preference vote between 1998 and 2022

Source: Northern Ireland Assembly Election 2022, House of Commons Library, Research Briefing by Matthew Burton 18 May 2022.

During the 2022 campaign, parties put forward very practical issues and decided not to lay stress on the constitutional question. The DUP manifesto, entitled “Our five points for Northern Ireland: Real Actions on the Issues that Matter to You” (DUP 2022: 1, emphasis in original) included one section devoted to the Northern Ireland Protocol, but all the other sections dealt with economic and social issues, pushing the constitutional question into the background. Sinn Féin as well opted not to focus on holding a referendum on unity. The plan for having a border poll and an all-island discussion on the matter came on page 9 of its manifesto, between plans for health and the party’s vision for the Northern Irish economy (Sinn Féin 2022: 9).

The 2022 election however was indeed an unprecedented election, but previous elections had already confirmed the rise of Sinn Féin, therefore the results were not totally unexpected. Besides, the idea of an electoral crisis for unionist parties has to be qualified for they still account for the majority in the Assembly although they are now neck and neck with nationalists.3

1.2 A divided unionist electorate

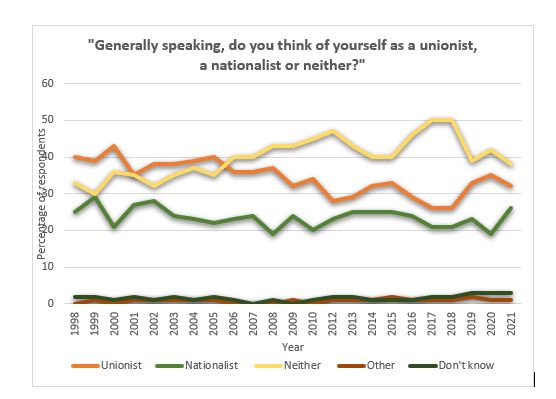

The most dramatic development came from neither end of the political spectrum, and it may represent the start of a long-lasting fight for former traditional unionist voters. The Alliance Party increased its vote share by 13.5% and won 17 seats. It was its best-ever election result and it gained 9 more seats than in the previous 2017 election. It managed to seize four seats from the SDLP, one from the UUP, two from the Greens and two as well from the DUP (Burton 2022). This non-aligned, non-ethnic party confirmed its gradual ascent by taking votes both from nationalist and unionist parties, but tapped mostly in the group of voters who identify as neither unionist nor nationalist. In his analysis of the 2022 election, Jonathan Tonge (2022: 528) examined the vote transfers in favour of Alliance: “Alliance received vote transfers from various sources: 23 per cent from the UUP, 21 per cent from Sinn Féin and 16 per cent from the SDLP. Alliance’s main vote, however, is from those identifying as neither unionist nor nationalist”. This group now amounts to 38% of the total electorate in Northern Ireland, in other words, the largest group and this represents a challenge for all parties, including for the DUP. As noted by Jonathan Tonge (2020: 463) in the 2019 election, Alliance started to garner more support and benefited from growing disaffection with the two main parties, the DUP and Sinn Féin. Indeed, the more moderate and middle-ground unionists, dissatisfied with the party, its internal rift since the ousting of Arlene Foster and the suspension of the Assembly once again, were reluctant to vote for the party. On the other hand, in 2022, the DUP lost more than 40,000 votes in the election, whereas the TUV gained the same amount. This suggests that more virulent unionists within the DUP also turned to another party, the TUV who adopted a very strong rhetoric against the Protocol, whereas the DUP was more hesitant when it was drafted, and asked to reform it (Murphy 2022). These trends combined, the DUP’s share of the unionist vote fell to its lowest level (Tonge 2022: 527).

1.3 A crisis of support for the main unionist party?

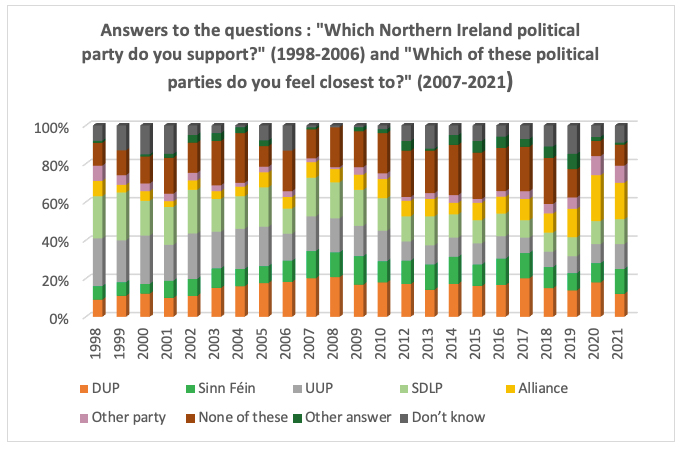

The question for the DUP is to know whether this is the sign of disaffection, of a short-term crisis of confidence between the party and its traditional voters or the first signs of a voting realignment in Northern Ireland. The Northern Ireland and Political Attitudes survey might provide an insight into this question.

Indeed, according to the results to the questions “Which Northern Ireland political party do you support?” (between 1998 and 2006) and “Which of these political parties do you feel closest to?” (2007-2021)4, the rates in favour of the DUP and Sinn Féin remained quite stable, to the detriment of the SDLP and the UUP which both experienced a downward trend. Yet, it is also worth noting that Alliance has been engaged on an upward trend, especially since 2017. Thus, the momentum this party gathered can be seen in its electoral results but also in the rate of support or the identification rate (although this is not similar to membership rates). The average support rate for Alliance was about 8.3% according to the Northern Ireland and Political Attitudes survey between 2009 and 2015, but between 2016 and 2021 it went up to 14.6%, achieving a steady rise close to 76%. At the same period, the support rate from the UUP dropped from an average of 12.1% between 2009 and 2015 to 10% between 2016 and 2021.5 The SDLP experienced a similar trend: from 14.6% between 2009 and 2015 to 11% in 2016-2021. The following graph illustrates Alliance’s increase over the last three years more specifically. It also shows that between 2003 and 2018 a large number of respondents felt close to none of the parties mentioned in the survey. This category tended to decrease as the last three years’ figures seem to suggest as well, which coincides with Alliance’s rise. It remains to be seen if these trends initiated three years ago will continue in the future.

Graph based on the results of the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey between 1998 and 2021, “Interest in politics, party affiliation” category.

The DUP’s drop in terms of support rate is not substantial, contrary to what the results of the 2022 elections could suggest. Many reasons might explain these figures and temporary disaffection with the party. The DUP went through a leadership crisis when Arlene Foster was ousted by her own colleagues in 2021. 80% of the DUP MPs and MLAs signed a vote of no confidence against her leading to her resignation. According to the party, her failed negotiations with Boris Johnson and her soft opposition to the Northern Ireland Protocol were the reasons behind the declining level of confidence in her leadership. Edwin Poots was elected as her successor; he represented a more conservative and traditionalist branch of the party. He was eventually ousted after less than three weeks at the head of the party because he took the decision to appoint Paul Givan as First Minister without asking for approval of other representatives. Givan remained the First Minister for a few months before Jeffrey Donaldson, the new leader of the party, eventually asked him to resign over the Northern Ireland Protocol. These internal rifts and tensions might have displeased the DUP’s traditional voting bloc. In addition, the party also refused to appoint a Deputy First Minister in 2022, opening a new period of uncertainty for the devolution settlement. It remains to be seen whether the alienation of some of the DUP’s voters might have long-term consequences and become more solidly entrenched in future elections.

The UUP also experienced a deep and long-term crisis. Despite its numerous attempts at adopting a more liberal and civic approach to unionism as will be shown below, the party has failed to regain the confidence of unionist voters.

The rise of Alliance raises a number of questions for unionist parties. As said above, the party taps into an ever-increasing group of voters who identify as neither nationalist nor unionist. In addition to these voters, more moderate unionists tend to turn to Alliance as well. Since the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, the rate of people who identify as neither nationalist nor unionist has slowly but steadily increased and it is now a decisive aspect for future elections in Northern Ireland.

Chart based on the results of the Northern Ireland Life and Times survey between 1998 and 2021, “Identity” category.

It requires unionist parties to adapt their discourse on the Union to convince voters for whom an emotional attachment to the UK and its history does not suffice. The DUP and the UUP have understood the need to develop a more pragmatic case for the Union, and notably its social and economic benefits to convince voters to remain in the UK in the case of a border poll. However, for the time being, in terms of electoral results, and support rate, this reorientation has proven insufficient.

However, unionist parties also have to accommodate a portion of less moderate voters who have turned to the TUV, believing that both the UUP and the DUP were being too soft and compromising during the negotiations on the Protocol with the British government. The unionist electorate appears very fragmented and hesitant to turn to the DUP more than in past elections. Some parts of the DUP voting bloc have taken different directions, and it remains to be seen if the party will manage to reconcile its electorate.

2. A sign of political dealignment or a short-term crisis?

Electoral performances provide an insight into the dynamics of political parties, but also in their capacity to build a growing coalition of voters and members. In addition to poor electoral results, the decline in party membership or in levels of membership participation can also suggest that a party is heading towards a crisis. It has been shown for example that although the UUP has a higher level of membership than the DUP, it lacks dynamism and has a lower level of activism than the DUP (Hennessey et al. 2019: 96). This part will show how Northern Irish unionist parties have tried to reach out to new voters and to what extent these strategies have been fruitful.

2.1 Party reorganisation and popular representation

In order to maintain effective levels of party membership and to ensure the participation of party members and sympathisers, the Northern Irish parties under study have tried to adjust their approach to party formulation by involving members and party sympathisers. In the case of Northern Ireland, unionist parties used to be largely centralised: firstly, because consociationalism implies a strong party leadership, a centralised decision-making process and rests on elite cooperation, secondly because the two main unionist parties have been led by charismatic leaders, which might indeed have reinforced this phenomenon. As noted by Hennessey et al. (2019), the UUP used to be led by “grandees” while new leaders try to stress their “ordinariness” (2019: 92). The same goes for the DUP which was created by Ian Paisley, who came to embody opposition to the Belfast / Good Friday Agreement and led the party until 2007. In his study devoted to the internal organisation of Northern Irish parties, Neil Matthews (2017) has shown how both the DUP and the UUP have tried to engage their members through new forms of participation in order to counter these centralising dynamics and to increase levels of participation.

Indeed, since devolution, they have reformed their intra-party organisation. For instance, both parties have formalised a new “supporter” category, perhaps because of lower membership rates. The DUP has adopted a “registered party supporters” category and in 2007 the UUP also reformed its membership registration system and created a “supporter” list. The party also offers a “stay informed option” on its website which can facilitate supporters’ input and involvement (Matthews 2017). The DUP has often been criticised for being too centralised and these reforms aimed at changing this image. For instance, in 2012, the party held its first “Spring Policy Conference” open to all party members and during which they could vote on a number of issues. Although these votes were not binding, they provided for the party leadership an important insight into levels of support. The party also created “Policy Development Forums” with thematic working groups (see Matthews 2017) whose purpose was to make party members more involved and to refute the idea that the party leadership was out of touch with its rank and file. The UUP endeavoured to give a say to members and sympathisers as well, by holding a series of public consultations in 2013 and by establishing “Policy Forums” in 2012 . Recently in 2020, a UUP councillor and former MLA for Strangford, Philip Smith, launched a project called “Uniting UK”. It aims to articulate a more positive vision of the Union and “to provide a challenge to organisations seeking border polls and a United Ireland”.6 Following the centenary of Northern Ireland, this pro-Union group wished to promote a more modern Union and to communicate more effectively. They adopted a grassroots strategy by asking pro-Union organisations and individuals to answer an online questionnaire, “Vision 2031” which included questions such as “In what ways might Northern Ireland benefit from staying in the UK, in the long-term?” or “What do you think are the biggest threats to the future of the Union?”.7 This appeal to grassroots members and organisations also testifies to this effort to reach out to the party’s electoral base and to listen to its input.

Over the last two decades, both the DUP and the UUP which used to be very centralised organisations have tried to reorganise themselves in order to make it easier for the rank-and-file to have a say in the policy formulation process, but also in order to reach out to members of the public beyond their electoral base. It remains to be seen the extent to which they have managed to convince voters beyond the sectarian divide.

Indeed, votes in Northern Ireland remain predominantly split along the nationalist / unionist divide, but within the unionist electorate itself there are other divisions that need to be accounted for.

2.2 The DUP vote: from realignment to dealignment?

In The People’s Choice, Lazarfeld et al. (1944) showed how important social characteristics were in determining one’s party choice, as they adopted a social determinism approach to show the large influence voters’ social environments and circles did have on their choice. Until the realignment of the early 2000s, the unionist vote was characterised by similar factors.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, unionist voters who were more likely to support the DUP were drawn from the lower social ranks, they were younger than other unionist voters and also less qualified. Evans and Duffy wrote: “It could be, therefore, that a link between the working class and support for the DUP is a result of the party’s position on economic/redistributive issues, especially in an environment where insecurities among economically less secure Protestants remain high” (1997: 58). Paradoxically, the young urban voters who supported the DUP were also less religious, although the party itself and its leadership had a strong religious identity (Evans and Duffy 1997: 56). However, in the wake of the negotiations on the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, there was a voting realignment in the unionist community. Indeed, by 2007, the DUP had become a “catch-all” party. Otto Kirchheimer coined this term in 1966 in “Transformation of the Western European Party Systems”8. Catch-all parties have therefore been characterised by their large and mainstream appeal, their search for rapid electoral success - at the expense of their ideological baggage -, their more centrist and consensual platforms likely to appeal to a wider range of voters, but also by their elite-driven organisation.

As far as the DUP is concerned, Tonge et al. explained this trend as follows:

The DUP’s transformation in fortunes has come about via its attraction of middle-class support. Whilst backing for the DUP had risen across all social classes, the steepest ascent was among the salariat, where support had risen from not much above 0 in 1989 to over 40% by 2006. Concurrently, the left-right dimension to DUP-UUP electoral competition has markedly diminished. (Tonge et al. 2014: 174)

The party benefitted from a combination of factors. It succeeded in reaching out to younger voters, including younger Protestants (ibid.) and younger members of the Orange Order, which was historically closest to the UUP. This phenomenon could be called a partisan realignment according to David Denver’s definition: “a situation in which voters align themselves with a party by thinking of themselves as supporters of it, by having a party identification” (1994: 32). These younger voters who came to support the DUP thought it was the most capable of defending their interests during the peace process and identified with the party. But the DUP also benefitted from another phenomenon. People who had been socialised in the UUP left the party to join Paisley’s. Many turned their backs on the party that had trained them as young politicians: Jeffrey Donaldson, Peter King, David Brewster, Gavin Adams, Lee Reynolds and even Arlene Foster who would later take the party’s leadership. The influx of new members who defected from the UUP led the party to recalibrate some of its positions, supporting the devolved assemblies and the implementation of all-island bodies for example, thereby convincing a new electorate to join them as the party tried to distance itself from its uncompromising reputation and its religious rhetoric (see Gomez and Tonge 2016).

The DUP has managed to modernise and create a large coalition of unionist voters. However, what seems to be at stake for the party now is to keep this coalition together as the unionist vote appears to be more and more fragmented. The party’s voting bloc remains younger than the UUP’s for instance but recent events beg the question of a potential dealignment of the unionist vote.

A partisan dealignment may originate in a couple of causes (Denver 1994): an increased political awareness that might explain why an emotional attachment to a political party might decline or secondly a disaffection of the electorate with the party and its leaders. In the case of the DUP, the second case might explain the result of the latest election, with some of its voters turning to Alliance and others to the TUV. It is too early to say however whether this trend will lead to a dealignment within the unionist electorate.9

2.3 The UUP: the 2022 “inclusive unionism” campaign

To provide a more “liberal” alternative to unionist voters, the UUP has changed its electoral strategy under Doug Beattie’s leadership. As confirmed by the latest elections, many unionist voters now feel politically homeless and the UUP has tried to reach out to those more liberal voters who might be tempted to vote for Alliance for example. The UUP has been campaigning for an “inclusive unionism” as opposed to an “inward-looking”, “angry” unionism as stated by Doug Beattie who was appointed leader of the party in May 2021. He wrote in an article on Eamon Mallie’s blog:

For some of them [people in Northern Ireland] voting for a unionist party means voting for the negative, angry, ‘wrap yourself in a flag’ unionism which they do not want as their vision for the future. Therefore, they stay at home and join the two thirds of non-voters who are unionists in their mind-set but not necessarily in their cultural outlook, or lend their vote to other political parties in the hope that at some stage unionism will wake up and promote a vision with which they can feel comfortable. (Beattie 2021)10

The UUP has tried to reach out to voters who identify as neither unionist nor nationalist, but it is also reaching out to people who identify as nationalist or Catholic and who might be convinced to remain in the Union for economic and social reasons. The 2022 manifesto laid stress for example on the role of the NHS during the Covid pandemic and the benefits of the Union’s healthcare system11: “The United Kingdom was the first Western nation in the world to authorise a Covid-19 vaccine, with our subsequent early access to vaccines reiterating the importance and benefit of Northern Ireland’s place within the Union” (UUP 2022: 5). During the 2022 campaign, the party insisted on creating a “Union of people”, home to people of different religions, political allegiances, backgrounds and sexual orientations (UUP 2022: 26). Indeed, the party is striving to extend its electoral base by having a more liberal and progressive discourse. By doing so, the party is trying to fill a gap on the Northern Irish political spectrum since there is room for a more liberal and progressive unionist party. The results of the election of 2022 have once more confirmed the political crisis that the UUP has been going through since the early noughties. It was the worst result for the party, which returned only 9 MLAs and reached a record low vote share. The challenge for the party is to show it is now able to endorse a more liberal, progressive and inclusive approach to political and social issues, thereby convincing voters beyond the unionist electorate only.

3. The Northern Ireland Protocol: deepening the crisis and strengthening polarisation?

In addition to declining levels of membership and activism and disappointing electoral results, the stalemate over the Northern Ireland Protocol might be seen as another trigger for a political crisis in Northern Ireland, and a further element of polarisation, although this concept needs qualifying.

3.1 A united “unionist” front?

Since its implementation, the Northern Ireland Protocol has been a source of tension and has even precipitated Northern Ireland in a new political crisis following the resignation of the DUP First Minister and more recently the party’s refusal to appoint a new Deputy First Minister in opposition to this text. The protocol aimed at safeguarding the open border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, thereby making Northern Ireland subject to EU product standards.

In its document “Remove the Northern Ireland Protocol”, the DUP stressed the two main flaws of the Protocol from its point of view: firstly, the creation of a border in the Irish Sea which set Northern Ireland apart from the rest of the UK, and secondly, the economic impact of checks on goods arriving in Northern Ireland (DUP April 2022: 5). All unionist parties oppose the Protocol and have tried to maintain a united front, despite the UUP being described as “softer” on the Protocol. The TUV was the first party to vehemently oppose the arrangement, soon followed by the DUP. The UUP on the other hand first advocated a reform of the bill.

Two years ago, a group of unionist politicians contested the legality of the Protocol in the High Court of Belfast. This group included representatives from the main unionist parties of Northern Ireland: TUV leader Jim Allister, Arlene Foster, the late David Trimble, UUP MLA Steve Aiken and also pro-Brexit property tycoon Benyamin Naeem Habib and ex-Labour MP Baroness Catharine Hoey of Lylehill and Rathlin. The Court rejected their case but it concluded that the Protocol conflicted with the Act of Union. The applicants used this point to go to the Court of Appeal, where their appeal was dismissed again before taking their case to the Supreme Court which released its decision in February 2023 and ruled that the Protocol did not breach the 1800 Act of Union and the 1998 Northern Ireland Act.12 This legal action testifies to Northern Irish Unionist parties’ shared position on the Protocol. Besides, on September 28th 2021, the four main unionist parties, the DUP, the UUP, the TUV and the PUP, published a joint declaration and released a video in which their leaders appeared together. The declaration read:

We, the undersigned unionist political leaders, affirm our position to the Northern Ireland Protocol, its mechanisms and structures and reaffirm our unalterable position that the protocol must be rejected and replaced by arrangements which fully respect Northern Ireland’s position as a constituent and integral part of the United Kingdom.13

This united front led to an arrangement between the DUP and the TUV which aimed to maximise the influence of the anti-Protocol group in the Assembly “through encouragement of lower preference votes being directed to each other’s party. The TUV has described it as a ‘pre-election pan-unionist pledge’” as Clara Rice summarised (2022: 38). Shows of unity among unionists are rare enough to be mentioned but this united front against the Protocol is also the sign of a deepening political crisis as well as a sign of polarisation over the constitutional question.

3.2 The Protocol and the polarisation of opinions

A political crisis may be characterised by a strong divide and increased polarisation. It is believed that power-sharing might have entrenched polarisation and that votes are extremely polarised in Northern Ireland when it comes to identity and constitutional questions. Thus, it appears that the protocol has worsened polarisation to a certain extent. Opinions on the deal have evolved over the last couple of years and have tended indeed to be more polarised as noted by Katy Hayward et al. (2022) in their analysis of public opinion on the protocol. In 2020, 16% of respondents answered that on balance the Protocol was a “good thing” for Northern Ireland, and it rose to 33% in 2021 (2022: 4). The figure for those who think that it is a “bad thing” also increased slightly from 18% to 21% while 33% think it is a “mixed bag” (as opposed to 46% in 2020). These figures are evidence of polarisation. Indeed, the largest opposition to this arrangement is to be found in the unionist community. The proportion of people who thinks that the agreement is on balance bad rose from 31% in 2020 to 44% in 2021, while 40% consider the agreement a “mixed bag” instead of 45% in 2020 (Hayward et al. 2022: 3). Thus, these figures indicate that opinions have indeed polarised on the Protocol because in the longer term it is related to the constitutional status of Northern Ireland and this is one of the main polarising issues in the region. Therefore, the current stalemate is still jeopardising the exit of the political crisis and the return to a functioning Assembly.

Nevertheless, although the idea according to which polarisation has increased due to the current situation needs to be qualified. The rise of a non-ethnic party such as Alliance for example could be evidence that some voters try to avoid polarisation along the traditional unionist / nationalist divide. Indeed, as shown by Matthew Whiting and Stefan Bauchowitz in their analysis of parties’ manifestoes (2022), economic and social issues are not as polarising as the constitutional question and Northern Irish parties are rather close as regards their position on more pragmatic questions, even as regards their position on the left-right divide (2022: 94). Besides, despite opinions being polarised on the Protocol, for many people, the Protocol does not rank among their highest concerns as a new poll carried out by Queen’s University has shown. David Phinnemore et al. summarised the result of the survey as follows:

The issue of most concern to voters is the health service (42%) followed by the economy/cost of living (31%). Three-quarters of voters place these issues as first and/or second in their ranking of concerns. The Protocol is ranked as their top concern by 22% of respondents; twice as many respondents (44%) rank the Protocol as the issue of least concern to them. (Phinnemore et al. 2023: 2)

The Protocol has undoubtedly polarised the political debate. However, the current political crisis has more to do with the political leadership being unable to come to an agreement and restore fully-functioning institutions, and with the DUP which still refuses to appoint a Deputy First Minister. The position of the party might satisfy their voters for 55% consider the Protocol top of their policy concerns but the party who has led Northern Ireland since 2007 has now become the most distrusted party among the wider electorate in Northern Ireland (67%, ibid.).

On February 27th 2023, the UK government and the EU announced a new Brexit deal for Northern Ireland, the “Windsor Framework”. Rishi Sunak claimed on the same day in the House of Commons that the Irish Sea border had been “removed”. The new deal will create two different statuses for goods going to Ireland and those staying in Northern Ireland. The latter will use the “green lane” and will no longer be physically checked. UK businesses exporting goods to Northern Ireland will also face minimal paperwork, which was one of the main hindrances of the former version of the protocol for companies and businesses. Moreover, the Trader Support Service is due to remain in place to help them with their trade bureaucracy. This deal will also allow the UK to change VAT, imposing it for instance on beverages based on their alcoholic strength or reducing it on goods such as solar panels for individual properties. On the other hand, goods going to the Republic of Ireland will take the “red lane” where they will continue to be physically checked and follow customs processes.

Following this announcement, Sinn Féin and the SDLP called for the restoration of the Assembly. However, at this stage, unionist parties seem to be reluctant to accept the deal as it is. The TUV leader, Jim Allister, claimed that the framework did not have the legal effect of the Protocol and that there was no explanation as to how it could be given precedence. The DUP has declared that it would now examine the clauses of the framework, but the party has already questioned the “Stormont Brake” defined in the official text as:

[An] emergency mechanism to allow the UK Government at the request of 30 MLAs to stop the application in Northern Ireland of amended or replacing EU legal provisions that may have a significant and lasting impact to everyday lives of communities there. (The Windsor Framework, 27 February 2023: 3)

The DUP MP Sammy Wilson has already criticised this measure for it would be the UK government who would have the final say and he believes that the government might be reluctant to veto a law by fear of the consequences for trade in the rest of the Union. Therefore, at this stage, there is no sign that the Northern Irish political crisis might end in the coming weeks and that the DUP is willing to appoint a Deputy First Minister to get the Assembly up and running again, thereby deepening political tensions in the region.

4. A larger crisis in British Unionism? Attempts at “reconnecting” Unionism

The crisis Northern Irish unionist parties are undergoing is not only a political and electoral crisis. Indeed, following the 2014 referendum on Scottish Independence, it seems that unionism as a political ideology could also be described as being in a state of crisis.

Of course, Northern Ireland has a different political system and a different devolutionary settlement. However, both in Northern Ireland and in the rest of the UK, unionists have been at a loss to provide a modern and positive view of unionism and Britishness. Unionism is about the links connecting the four nations of the UK but concerns over a potential fragmentation of the Union emerged in the wake of the 2014 and 2016 referenda. Thus, can the idea of “crisis of unionism” apply to British unionism more broadly speaking?

4.1 The example of Scottish unionism

As noted by the former Scottish Conservative leader Ruth Davidson, the fates of the different nations of the UK are linked together. In “What Hope for the UK?”, an article she wrote in December 2021, she insisted on the need to have a broader view on unionism and on the need for British unionist parties to look at Northern Ireland, after having been “obsessed” with the Scottish Question since 2014. She wrote:

For me, the fabric of the UK is always in tension. And the “otherness” of my part of it, is, in part, offset by the “otherness” of Northern Ireland. What I couldn’t say, all those years ago, to the nationalist politicians impressing upon me Scotland’s potential role in Irish reunification, was that they were probably right. I see the counterbalance that one province provides the other and can accept that Scottish secession, had it occurred, may well have helped tip majority opinion in Northern Ireland towards Irish reunification. And if I accept that, I must push myself to acknowledge the counter may also be true. (Ruth Davidson 2021)14

She went on to praise the liberal and inclusive vision of unionism of the UUP leader Doug Beattie whom she argued could save unionism. She seemed to believe that the considerable changes initiated by Beattie could help create a more “connected” unionism between the different nations of the UK, based on a stronger relationship and a more inclusive definition of unionism.

Davidson herself played a large role in trying to redefine political unionism and more specifically Scottish Unionism. In 2012, she founded the association “Friends of the Union”, a think-tank which purported to give shape to a more connected unionism, gathering unionists from all nations of the UK, including Northern Ireland.

Under Davidson’s leadership, the party endeavoured to rebrand and modernise Scottish unionism.15 They gradually reasserted their “nationalist unionist” credentials and wished to represent a more “constructive unionism” as Davidson argued that the Scottish Conservatives did also represent another brand of Scottish nationalism, which was not incompatible with being a member of the British nation-state. (Davidson 2015)16

This rebranding of Scottish unionism as a kind of “nationalist unionist” one bore fruit in the 2016 election. The SNP remained the largest party with 63 MSPs, while the Scottish Tories came second with 31 MPs, increasing their vote share by 8.1% and pushing the Scottish Labour into third place.17 The Scottish Conservatives presented themselves as a “strong unionist opposition” to the SNP and framed the campaign as a nationalist vs unionist debate (Scottish Conservative and Unionist Party manifesto 2016). In the 2021 Scottish Parliament election, the Scottish Tories retained their second place. The 2017 Westminster elections saw the Scottish Conservative Party lose seats in Scotland, although the party came second, losing seven seats to the SNP and winning 25.1% of vote share, in other words 3.5% less than in 2017.18 One reason that might explain these results is that the Scottish branch of the Conservative Party found itself in the difficult position of having campaigned against Brexit while belonging to the party that took the UK out of the EU. Douglas Ross, the current leader of the Scottish Tories, advocated a reform of the Union and more autonomy for devolved territories. Upon his election as leader, he criticised the British government’s unitarist approach to the Brexit negotiations. Indeed, under Johnson’s premiership, the repatriation of Brussels’s powers to London was seen as a step back for the Scottish Conservatives who had striven to make their support for devolution and for extended devolved powers known after their initial opposition to the devolutionary settlement. But the Scottish Tories were not the only ones to struggle promoting unionism in Scotland.

Adopting a progressive and positive discourse on the Union also proved to be a challenge for the Scottish Labour party, as noted by Kieran Wright who analysed the positioning of the Scottish Labour Party following the SNP’s victory in 2007. He came to the conclusion that the party had consistently failed to make a positive case for the Union. He wrote:

On losing power at Holyrood the party appears to have down-played the progressive case for the union relying increasingly on dry, economic justifications that undermined its image as a clearly left of centre, progressive party. […] Labour’s strategy post-2007 left a gap in Scottish political discourse where the progressive case for the union was underplayed, allowing the SNP to make the case that independence constitutes the more progressive option on the constitutional issue largely unchallenged. (Wright 2022: 630)

However, it appears that the constitutional question had a strong influence on the vote in the 2021 Scottish Parliament election. Studies have shown that unionist voters, in order to defeat the SNP, were willing to support other unionist parties in spite of the left-right divide: “Of Labour constituency voters who cast a split-ticket, 60% voted for the Scottish Conservatives on the list. Similarly, a plurality of Conservative splitters voted for the Labour Party on the list (40%)” (Aisla Henderson et al. 2021: 16). Although these two parties are at opposite ends of the political spectrum, voters would express support for the most pro-union parties to defeat the SNP candidates.

This voting trend seems to confirm that unionist voters are concerned with the constitutional question more than ever, thereby replacing this question at the heart of the political debate in Scotland.

These vote transfers might also call into question the definition of unionism put forward by these parties. Indeed, these unionist parties, when asked to give arguments in favour of the Union, tend to give the same types of ideas, although adopting slightly different positions.

During the 2014 referendum campaign, the main arguments on the unionist side were economic and social. Unionists would refer to the safety provided by the NHS - a symbol of British unity, EU membership or the defence policies. Daniel Cetrà & Coree Brown Swan (2022) showed that the main unionist parties promote the Union by using three main arguments. The first one is the safety net that being a member of an economic union represents, secondly, the welfare state and the social union, and thirdly the belief in British values such as the rule of law, pluralism and democracy (Cetrà and Swan 2022: 651). As noted by the authors, the Labour Party is likely to have a more “dynamic” approach to these questions, advocating for example a reform of the NHS and of the economic union, while they describe the Tories’ position as more “static”, as they are keener to allude to the history of the NHS and the Union as the symbols of a national narrative.

However, the endeavour to redefine and modernise the discourse on unionism goes beyond party politics and a number of pro-Union movements have been concerned with “reconnecting” unionism at the UK level.

4.2 The need for a “connected unionism”

There have been a number of initiatives aiming to reawaken unionism. For example, in 2015, a cross-party group of politicians founded the Constitution Reform Group to address the question of the reconfiguration of the Union. This group includes academics and politicians from the entire unionist political spectrum. Founded out of concern for the future of the Union, the Constitution Reform Group advocates a new Act of Union based on a more federal organisation, giving England its own parliament and acknowledging self-determination for each nation of the UK. The central government would deal with “central issues” but local governments and legislatures would legislate on all other questions. This organisation would tend to be more federal in its outlook (Constitution Reform Group 2015, 2018). Thus, a number of organisations have striven to modernise and reform the Union as a constitutional settlement but also unionism as a culture and an identity.

For example, the “These Islands” forum that was founded in 2017 is also a cross-party organisation. While the Constitution Reform Group focuses on constitutional issues by promoting a New Act of Union, “These Islands” as a political forum aims to promote the historical links between the nations of the UK and the promotion of a British sense of identity based on pluralism as well as “local identities and loyalties”. The group’s main actions consist in organising conferences and publishing papers whose purpose is to put forward a positive and enthusiastic case for the Union and promote a “recalibration” of Unionism based on a “sense of optimism and relish”.19 These organisations are home to people of different political traditions and drawn from all parts of the UK. They purport to revamp and modernise unionism in the wake of the 2014 and 2016 referendums.

There is one more initiative that is worth mentioning in this section. The book The Idea of the Union was first published in 1995 by John Wilson Foster as a handbook of arguments to defend the place of Northern Ireland within the Union. Pro-Union academics and commentators wrote about their vision of the Union, its constitutional and cultural aspects, and why they wanted to retain their British identity. The objective was to make a clear, positive and well-argued case for the Union. The Idea of the Union was reedited by John Wilson Foster and William Beattie Smith in 2021. As explained in the introduction by John Wilson Foster, the aim of this reedition has not changed since 1995, for he argues that Brexit has “reinvigorated” the campaign for a united Ireland (John Wilson Foster 2018: 18). This time however, the focus is not on Northern Ireland solely and Wilson Foster urges unionists from Scotland, Wales and England to fully engage in the defence of the Union as the Northern Irish did. He wrote:

Perhaps the looming crisis is timely for Northern Irish unionists, disturbing though the coincidence is […]. Scottish unionists can exploit our experience in the matter and draw profitably on some of our seasoned arguments. And perhaps in doing so – this is devoutly to be wished - they can see the similarities between the challenges they face and realities they need to reaffirm and those challenges and realities unionists across the narrow water have been grappling with against the odds for a very long time. (John Wilson Foster 2018:: 32)

Foster laments the fact that efforts to theorise Unionism have been circumscribed to Northern Ireland and that unionists from other parts of the UK have never really engaged in this conversation. Now that the other parts of the UK, notably Scotland, are facing the challenge of fragmentation, he calls on unionists of all political traditions to rethink their unionist vision for the 21st century. This book gathers thirteen contributions from Northern Ireland, three from the Republic of Ireland, three from Scotland and two contributions from England, showing the archipelagic dimension of their approach to unionism. Contributors all insist on the need to develop a coherent and cohesive discourse on the Union at the UK level, giving shape to a more connected unionism. The book however does not present a unique definition of what unionism could become but it aims to strike up a conversation on the future of the Union. For Arthur Aughey for example, Britain should be seen as a state and not a nation, for if it claims to be inclusive of plural identities, religions and cultures then it cannot have a “natural” or “biological” basis of unity (John Wilson Foster 2018: 239) . On the other hand, William J.V. Neill advocates a cultural unionist identity:

Any attempt to distil the essence of unionism in more neutral, dry constitutional/legal relationships, obligations and rights or even economic interests, important as these may be, does not get to the more visceral cultural factors generating broad group identity. (John Wilson Foster 2018: 358)

The reedition of an updated version of The Idea of the Union suggests that modern-day unionism is still facing a deep ideological crisis, as it lacks articulate and positive arguments. These different initiatives have a similar aim: creating connections between unionist movements at the UK level and try to fill in the ideological gaps of modern-day unionism at the UK level.

Conclusion

This broad discussion on the future of the Union is taking place at a time when the rise of separatist movements and nationalist parties is already well entrenched. The results of the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence might have temporarily comforted unionists in all parts of the UK of the strength of the Union, but the Brexit referendum followed by demands for new border polls in Northern Ireland and Scotland has overturned the situation.

The centralisation of the negotiation process during the Brexit deal in London and the repatriation of EU powers in Westminster have also placed unionist parties in devolved territories in a difficult position. In addition, the good electoral results of nationalist parties in Scotland and Northern Ireland have made the threat of fragmentation of the Union even more salient. These elements may confirm indeed that unionism as a political ideology is currently in a state of crisis.

The Northern Ireland Protocol has also precipitated Northern Ireland into a new political crisis and has worsened the already existing tensions between the British government and Northern Irish unionist leaders. Besides, the latest electoral results of unionist parties seem to suggest that indeed they are going through an electoral crisis as well. The rise of a non-aligned group of voters represents a considerable challenge for unionist parties who should articulate a more pragmatic and inclusive case for the Union, something they have failed to do so far. If these trends are confirmed in the next election, it could lead to a realignment of the electorate in Northern Ireland, to the detriment indeed of Northern Irish unionism.