As underlined in August 2021 by Harry Thompson, then Economic Policy Lead at the Institute of Welsh Affairs in Cardiff, “for a party that had become accustomed to consistent electoral disappointment at a UK level, this renewed and active mandate in their [Welsh Labour] governance was energising” (Thompson 2021). Indeed, in the May 2021 Senedd election, Welsh Labour, which has come first at every British general election in the country since 1922 and is the largest party in Wales ever since the first Welsh elections in 1999, matched its best ever result at a devolved election and almost its best ever vote share. This result could therefore be interpreted as a vote of confidence in both Welsh Labour and the devolution project itself, introduced by the Labour Party back in 1997 and enlarged and embodied by the Welsh party since its introduction. The very label “Welsh Labour Party” was introduced in 1997 when Tony Blair, on becoming Prime Minister and pledging to introduce devolution, appointed Ron Davies as Secretary of State for Wales and first leader of Welsh Labour. Still, it is only a branch of the UK-wide party, working with a top-down organisation and not a federal system like the Liberal-Democratic Party. To a certain extent, it can be said that the British Labour Party decided to apply devolution to its own structure and organisation. Devolution has created a new political arena that works differently from the British one.

In Giovanni Sartori’s classification (Sartori 1976), the Welsh political system can be regarded as a partisan system with a predominant party, in other words, a party governing without alternation, on its own, which is more or less the case for the Welsh Labour Party. He suggests a mathematical analysis that can be applied to Wales: a 10-point gap in the number of seats translated into vote share between the first two parties means the first one can be considered as a majority party. As illustrated in the following table, this is clearly the case with Welsh Labour, which can hence be regarded as the predominant party in Wales:

Table 1: Welsh elections since May 1999 (figures compiled by the author).

| Election | Party coming first | Party coming second | Gap (%) |

| May 1999 | Welsh Labour 28 seats 46.7% | Plaid Cymru 17 seats 28.3% | 18.4 |

| May 2003 | Welsh Labour 30 seats 50% | Plaid Cymru 12 seats 20% | 30 |

| May 2007 | Welsh Labour 26 seats 43.3% | Plaid Cymru 15 seats 25% | 18.3 |

| May 2011 | Welsh Labour 30 seats 50% | Welsh Conservatives 14 seats 23.3% | 26.7 |

| May 2016 | Welsh Labour 29 seats 48.3% | Plaid Cymru 12 seats 20% | 28.3 |

| May 2021 | Welsh Labour 30 seats 50% | Welsh Conservatives 16 seats 26.7% | 23.3 |

Such an unquestioned success by a single party in Wales must be analysed and has been the subject of many academic studies over the last two decades1, especially by the Wales Governance Centre based in Cardiff. The Centre was established in 1999 in response to the creation of the National Assembly for Wales and its related devolved institutions and has, especially since the appointment of Professor Richard Wyn Jones as its director in 2009, conducted research on political, constitutional and policy themes in Wales. It regularly proposes deep analyses of Welsh politics and elections, notably the fate of the Labour Party in Wales, compared not only to that of the Party in Scotland, but also to the UK-wide party.

The main First Ministers to have governed Wales since 1999 – Rhodri Morgan, Carwyn Jones and, today, Mark Drakeford – have each in turn been able to maintain the party in power by defining a specific identity for Labour in Wales, neither old nor new Labour in the 2000s, nor British Labour more recently, but Welsh Labour. Furthermore, the on-going success of Welsh Labour since the introduction of introduction leads us to also consider the party in action: its strength is inevitably linked with the policies that the Welsh Labour Government has implemented since 1999.

This article aims to study how the Welsh Labour Party has managed to free itself from the UK-wide Labour Party, a party in crisis in recent years – an opposition party torn by factional struggles since 2010 – just as Wales has obtained an enlarged devolution settlement, by sounding both more Welsh and more radical than the UK-wide party, thereby allowing the Welsh First Minister to be the highest-ranking Labour politician in the United Kingdom since 2010.

After a brief historical presentation of Welsh Labour and its specific ideology since 2000, especially the implementation after 2002 of “Clear Red Water” policies by Rhodri Morgan, this article will study what makes Welsh Labour today appear far more radical than the UK-wide party. It will also consider the impact of the cooperation agreement signed with Plaid Cymru in November 2021 and intended to create, for Drakeford, “a stable Senedd capable of delivering radical change and reform” (Morris 2021). Yet, its radical ambitions have been partly thwarted over the last few years by a sharp recentralisation of power in London by the Conservative government, which may weaken the Labour Party in Wales.

1. Sounding more Welsh

As indicated by Jac M. Larner, Richard Wyn Jones, Ed Gareth Poole, Paula Surridge, and Daniel Wincott in an article on the 2021 Welsh elections, “[t]hus far, three of the four Labour leaders in Wales since devolution have both embodied and embraced Welsh Labour status as both a national and a centre-left party. It remains to be seen if that pattern continues” (Larner et al. 2022). Indeed, the main First Ministers since devolution2 have been able to assert the Welsh identity of the Labour Party. Rhodri Morgan (2000-2009) coined the expression “Clear Red Water”, then his successor Carwyn Jones (2009-2018) developed it, after which Mark Drakeford (First Minister since 2018), who used to write Rhodri Morgan’s speeches in the early noughties, distinguished himself in his handling of economic policies. All of them understood the power of soft nationalism to devise specifically made-in-Wales policies, so as to compete with Plaid Cymru, the nationalist party.

1.1. Welsh Labour vs New Labour: “Clear red water” between the two

Rhodri Morgan is presented by Kevin Brennan and Mark Drakeford in the foreword to his autobiography as “the kind of effective bridge between Wales and Westminster that was essential to the success of Welsh devolution” (Brennan & Drakeford 2017: x). As the ancient Welsh saying goes, “A fo ben bid bont – if you want to lead, be a bridge”. He was indeed regarded as a truly Welsh politician, not one imposed by the UK-wide party, contrary to Alun Michael, his predecessor, seen as imposed by Tony Blair in 1999.

Yet, he very soon made his mark by displaying strong leadership. First, he symbolically changed his title from First Secretary to First Minister on 16 October 2000. Then, more importantly, he acknowledged the sharp differences between Labour in Westminster and in Wales, thus echoing Ron Davies, Secretary of State for Wales between May 1997 and October 1998, the first leader of Welsh Labour – a position created by Tony Blair – and one of the architects of devolution. In 1999, he insisted on the specificity of Welsh Labour:

From 1994 a new vocabulary had crept into Labour’s lexicon. Party members were now supposed to be, at least in the eyes of the media, either New Labour or Old Labour although truth to tell many of us were neither. […] There was, I always thought, a third strand. Not New Labour or Old Labour but Welsh Labour (Davies 1999: 6).

Rhodri Morgan hence wanted to be a leader who was different from Tony Blair, one who represented Wales’s interests and implemented specific policies, meant to be Welsh policies, a difference which he called “clear red water” between Welsh and British policies in a speech he delivered in December 2002 at the National Centre for Public Policy at Swansea University:

I will wish to say a little more about the issue of distinctiveness, the so-called “clear red water”, as The Guardian inevitably put it and which has emerged over the lifetime of my administration between the way in which things are being shaped in Wales and the direction being followed at Westminster for equivalent services. […] The actions of the Welsh Assembly Government clearly are more to the tradition of Titmus, Tawney, Beveridge and Bevan than those of Hayek and Friedman. The creation of a new set of citizenship rights has been a key theme in the first four years of the Assembly (Morgan 2003: 13-14).

Thus, Morgan was willing to defend traditional Labour values, which he called “Classic Labour” and which, in his opinion, was endangered by the advent of New Labour. His agenda was clearly more left-of-centre than that of the Blair government in Westminster, as illustrated by his desire to offer free access to social welfare services, such as free prescription charges in 2007 – a symbolic move later implemented in Northern Ireland (2010) and Scotland (2011) – or the opposition to plans to introduce competition into public services. Morgan’s desire to set up different policies from the Blair government is well illustrated as much in the measures introduced by the governments he led as in what his ministers in Cardiff chose not to implement, thereby refusing to follow the lead of Westminster governments run by either the Labour Party or the Conservatives. Cathy Owens (Williamson 2017), a Labour special adviser to the Welsh government between 2003 and 2006, stressed that as indicated earlier, the Assembly refused to introduce any competition in public services, as well as grammar schools or academies in education, deciding on the contrary (for instance) to invest in charitable and third sector organisations and to dissolve quangos, considering it was time for a “bonfire of the quangos”. Such policies reflected characteristics commonly attributed to the Welsh people, such as the importance of the community and solidarity.

Rhodri Morgan was hence regarded as a crypto-nationalist, a description he rejected, preferring to define himself in the following way, in his autobiography: “I’m an instinctive devolutionist. And that doesn’t make me a crypto-Nat. There has to be a middle-ground filled by devolution, halfway between unionism and nationalism” (Morgan 2017: 332). By the way, he appreciated his time in coalition with Plaid Cymru – between 2007 and 2009 when he resigned – particularly because, as he put it, if when he died a post-mortem were to be performed, they would find he was half the red of Labour and half the green of Plaid, quite a paradoxical remark for someone refusing to be regarded as a nationalist. He concluded by defining “the Morgan brand” in the following way: “We should put aside all that stuff about Old Labour, New Labour, Antediluvian Labour or, as I prefer to call it, Classic Labour. With the advantage of hindsight, the Morgan brand is best summarised as Default Option Labour” (Morgan 2017: 332).

According to Professor Roger Awan-Scully, a former member of the Wales Governance Centre in Cardiff, the Welsh Labour Party has been able to promote a form of “Welsh branding”, allowing it to successfully compete with Plaid Cymru, the nationalist party, contrary to the Scottish Labour Party, largely beaten by the SNP. In an article published in May 2018, Alistair Clark and Lynn Bennie, two academics, analysed the manifestos published by political parties for subnational elections and classified them into three categories: contract manifestos, oriented towards office seeking; advertisement manifestos aiming to promote the party and associated with vote-seeking parties; and identity manifestos, associated with policy-seeking parties. They concluded that Welsh Labour’s manifestos since devolution, especially the one published for the 2020 British elections, were an example of the last category (Clark & Bennie 2018). Insisting on the Welsh identity has allowed Welsh Labour to offer a reassuring alternative to voters willing to see specific policies implemented in Wales but opposed to independence, hence an alternative to both Plaid Cymru and the Conservatives.

1.2. Welsh Labour vs British Conservatives

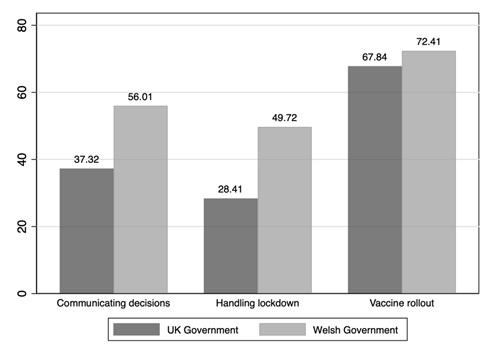

That strategy was developed by Carwyn Jones, who, after 2010, found himself in an unprecedented position, since he had to work with a coalition government led by the Conservatives in London. There came to be clear red water between Welsh Labour and the Conservatives. He hence became the highest-ranking Labour official in the United Kingdom, a position also held today by Mark Drakeford, made highly visible during the Covid-19 crisis, with his daily press conferences and handling of the pandemic that was seen as better – as revealed by several polls – than the British government’s. Indeed, polls, difficult to unpick though they are, suggest the public were far more responsive to Mark Drakeford’s methodical style of leadership and communication. Though frustrations grew with the First Minister in the later stages of the pandemic, there is self-evident advantage in having a leader who is demonstrably across his brief, as opposed to Boris Johnson’s errors in messaging and lack of seriousness, as well as misleading comments around rules in different parts of the UK. There is no denying that both leaders were attempting to make political gains, and it seems that Mark Drakeford’s government was more successful since their diverging handling of the pandemic was believed to be one of the primary reasons for Welsh Labour’s success and Drakeford’s massive re-election3 in May 2021. Since health is a devolved matter, the Welsh government could make its own decisions. In April 2021, the pre-election wave of the Welsh Election Study asked respondents how good or bad a job the Welsh Government was doing of handling different aspects related to the Covid-19 pandemic. As a point of comparison, they were also asked to evaluate how the UK Government had done on the same areas in England. Figure 1, below, shows the percentage of respondents who thought that each level of government did a good job on communicating decisions, handling lockdowns, and handling the vaccine rollout (Welsh Election Study 2021).

Figure 1: Percentage of respondents agreeing that UK/Welsh Government had done a good job of handling COVID-19 policy. areas. N = 4,072. Data are weighted.

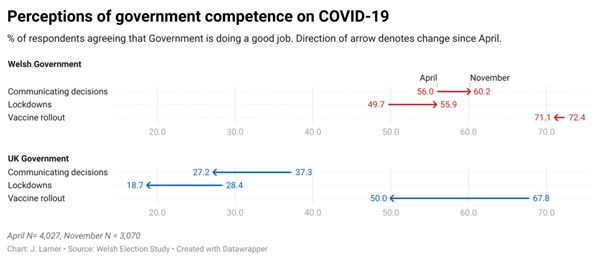

A substantially higher share of respondents thought that the Welsh Government was doing a better job on each policy area. In fact, the only really positive evaluation of the UK Government’s performance was on the vaccine rollout. At election time, it seemed like the more cautious approach of the Welsh Government was being rewarded by voters. In November, the same respondents were asked the same questions to see how evaluations had changed. The data were collected between 5 November and 23 November. This was prior to the discovery of the Omicron variant and the Downing Street party scandal, but after Conservative MP Owen Paterson had resigned in the wake of a sleaze scandal. Cases were also considerably lower than they had been in December when the second survey was carried out. Figure 2 below shows the change in the percentage of respondents who thought that each level of government was doing a good job, with the arrows noting the direction of change between April and December 2021. The picture is stark, with different stories for both governments.

Figure 2: Perceptions of government competence on COVID-19 (UK and Wales)

For the Welsh Government the news was positive with evaluations of their communication and handling of lockdowns improving and essentially no change in their handling of the vaccine rollout. By contrast, evaluations of the UK Government had fallen drastically from their already much lower level. Respondents appeared to be particularly scathing of the UK Government’s handling of lockdowns, with fewer than one in five thinking that it was doing a good job.

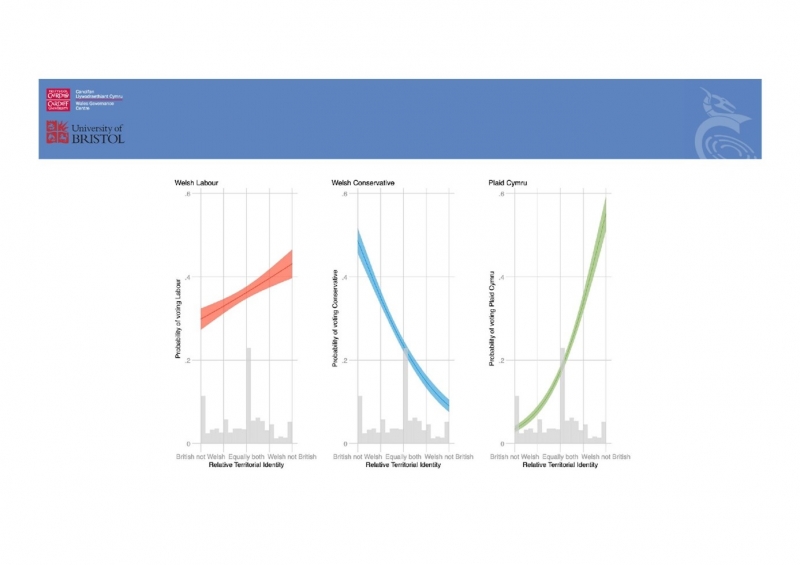

Welsh Labour, both unionist and nationalist, has thus been able to unify a traditionally fragmented country – into Welsh-speaking vs English-speaking and urban vs rural areas – as indicated by Theo Davies-Lewis, chief political commentator for the Welsh website The National, in an article published on 25 September 2021 and entitled “Starmer must learn the lessons of Welsh Labour”: “In a country where there are multiple identities, divided by geography, language, or socio-economic backgrounds, it is not impossible to become a natural national party of government.” (Davies-Lewis 2021). He considered that Keir Starmer, the Labour leader, should not dismiss “Celtic nationalism” and stop opposing nationalism, which Starmer regarded as an attempt to divide people from one another, and patriotism, presented as an attempt to unite people of different backgrounds. This capacity to unify Wales is well illustrated by the initial findings of the Wales Election Study 2021, published on 9 June 2021 by Jac Larner, Paula Surridge and Richard Wyn Jones: in the last Senedd elections in May 2021, 40% of people feeling Welsh voted for Labour, but also 25% of people feeling British, and 29% of Welsh-speakers. Welsh Labour was also attractive among all people, whatever their relative territorial identity. Besides, 42% of independence supporters voted for Labour, and 46% for Plaid Cymru (Larner, Surridge & Wyn Jones 2021), which shows the extent to which Welsh Labour can attract different types of voters, both nationalist and unionist.

Figure 3: Relative territorial identity and vote.

Larner, Surridge & Wyn Jones 2021.

Hence, Welsh Labour is in a very comfortable position as opposed to the Welsh Conservatives who are calling for the abolition of the Senedd, while Plaid Cymru advocates independence for Wales. It is also far more successful than Scottish Labour, unable, as indicated previously, to promote its Scottish specificity and attract enough voters to govern in Scotland. Consequently, the Welsh Labour Party manages to push its Welsh credentials and assert its distinctiveness from the UK party, while remaining, at least for now, committed to the union, which gives the party quite a clear identity. Such a comfortable position has allowed it to introduce more radical policies.

2. Looking more radical: Welsh Labour appearing more radical than the UK-wide party

A report edited by First Minister Mark Drakeford and Labour chair Anneliese Dodds, entitled Stronger Together: Labour Works, aimed to showcase “the bold, ambitious and radical change that Labour in power is delivering” (Labour Party 2022), elaborating on the Welsh model. Indeed, according to Theo Davies-Lewis:

Mark Drakeford, and the Welsh Labour carved in his image for two decades, is the best model for UK Labour, a model to avoid that fate [defeat in 2024]. The Road Ahead4 is not certain for Starmer – but one thing is: all roads don’t lead to Rome, but, of course, to Cardiff. (Davies-Lewis 2021)

It is therefore necessary to wonder what makes Welsh Labour’s radical policies a model, across a range of areas. Since sustainable development is an essential element of all policies in Wales – as inscribed in the Government of Wales Act 1998 – one illustration of the radical change Welsh Labour has been willing to make for each pillar of sustainable development will now be studied.

2.1. Protecting the Welsh environment

After the 2011 referendum on full law-making powers, the Senedd voted two major acts related to sustainable development, especially the protection of the environment: first, the Well-being of Future Generations Act in April 2015 with a clear objective then defined by Carwyn Jones:

We will legislate to embed sustainable development as the central organising principle in all our actions across government and all public bodies, by bringing forward a sustainable development Bill. The approach will set Wales apart as a sustainable nation, leading from the front. (Johnes 2013: 4)

This major act was regarded as a highly radical measure, setting Wales apart on the global stage, as stressed by Anne Meikle, Director of WWF Cymru since 2009:

When Carl5 came into post, he was the fourth Minister who had worked on the Well-being of Future Generations Act. It was not popular and was not effective. Carl was initially unconvinced about how it would help people. But he listened and responded to our requests for amendments, and once he got behind the legislation he was very effective at getting it through. The result was a truly radical law to ensure that sustainable development is at the heart of Government and public services, which has won global recognition. (Miller, 2017)

Forty-four public bodies are concerned by the act, such as local authorities, National Parks Authorities or Local Health Boards. It was paired to a second one, the Environment (Wales) Act 2016, adopted in March 2016, making it a statutory duty to sustainably manage natural resources in Wales, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050, to better manage waste, and to encourage recycling. Those major acts were promoted by the Welsh Labour Party in the Senedd.

2.2. Developing the Welsh economy

The Welsh Labour Government, especially since the 2008 global economic crisis, has implemented rather interventionist policies to save and create jobs in Wales, which has been affected by high unemployment rates (nearly 10% in 2010 compared to 8% in the United Kingdom in general)6. Carwyn Jones especially, in sharp contrast with the austerity measures introduced by the Cameron Government, defended a radical interventionist policy, which, unusually for Labour and quite differently from its traditional policies, entailed promoting a strong partnership with the private sector. This was underlined by previous First Minister Rhodri Morgan himself: “That’s why Carwyn Jones describes the Welsh Labour government as ‘business friendly’ – Jeremy Corbyn and the Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell have never described the party in those terms” (Morgan 2016). Jones’s original stance was also stressed in the headline of an article published in April 2017 in The Telegraph: “Carwyn Jones: ‘business’ is not a dirty word to Labour in Wales”. The Welsh Government initiated several employment schemes and did not hesitate to invest in schemes helping unemployed people to find a job, such as Jobs Growth Wales, introduced in 2012 for unemployed 16-to-24-year-olds – in this scheme, which helped create 15,000 jobs, wages were paid by the government for 6 months –or Jobs Growth Wales 2, launched in September 2015. The Welsh Government has also been deeply committed to attracting companies to Wales, such as Aston Martin which was established on the former RAF base in Saint Athan, Glamorgan, the company being awarded a £5.8 million subsidy. In February 2023, the unemployment rate in Wales was 3.5%, compared with a UK rate of 3.7%, even if the proportion of economically inactive people in Wales (25.5%), made up of students, the retired, and those who are long-term sick or disabled, was higher than in the United Kingdom (21.4%) (Government of Wales 2023). Statistics compiled on the website statista.com, the statistics portal for market data, market research and market studies (https://www.statista.com/statistics/529486/unemployment-rate-of-wales/) reveal that since 2010, the unemployment rate in Wales has regularly decreased, except in 2020 when there was an increase due to Covid.

2.3. Preserving welfare in Wales

More recently, in August 2021, First Minister Mark Drakeford unveiled the Welsh Government’s plan to trial a Basic Income Pilot Scheme “with the potential to offer groundbreaking, real-life insights into the effects of the policy” (Thompson 2021). This scheme, officially announced in February 2022 in the Programme for Government 2021-2026, is a set of regular payments to care leavers to provide them with a reliable income that will sufficiently free them to make a different set of decisions about their futures beyond the immediate. The three-year pilot scheme was to offer £1,600 a month to every care leaver over 18 and it was expected that about 500 people would be eligible to join the scheme which may cost up to £20m. Welsh Parliament member Jack Sargeant, who led the Senedd’s first debate on Universal Basic Income (UBI), said: “This is an incredibly bold move from a Welsh government that is leading the world in this area. We now need to ensure that we learn all we can from this trial. This is a real opportunity to show things can be different” (Morris 2022). UBI has been a topical issue for a few years now, but Wales was among the first countries to try it. The scheme was officially launched on 1 July 2022 and presented on the occasion by First Minister Mark Drakeford as a “radical initiative [that] will not only improve the lives of those taking part in the pilot, but will reap rewards for the rest of Welsh society. If we succeed in what we are attempting today this will be just the first step in what could be a journey that benefits generations to come” (Government of Wales 2022). A report commissioned by Sophie Howe, the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, and published by Autonomy, a thinktank, in November 2021, stressed the impact a Universal Basic Income may have on poverty levels: “The impact of even an introductory basic income scheme upon livelihoods in Wales would be life-changing for many. […] Poverty7 levels would decrease by half (from 23% to just over 11%)” (Autonomy 2021: 97). A more ambitious scheme would, according to Autonomy, wipe out poverty in Wales (Autonomy 2021: 108).

It thus seems that Welsh Labour is clearly an anomaly on the British political scene, managing to assert a Welsh identity and to introduce radical measures, thus often taken to be “a conveniently ‘socialist’ foil, aiming to introduce universalism, against which to contrast the failings of the UK’s Conservative Government, or the timidities of the Starmer leadership” (Kellam 2021). Yet, after being in power for more than two decades, Welsh Labour must analyse whether these radical measures have really changed Welsh people’s lives and will allow the party to remain the predominant party in Wales or lead to a potential crisis if the party was to disappoint its voters. To what extent will it be able to keep attracting voters if it fails to keep promises made?

3. The future of Welsh Labour, or what perspectives?

The Welsh Labour Party has to face two challenges: first, it has been in power since 1999, so that it is now held accountable for the impact, sometimes seen by experts as limited, that the policies introduced have had on people’s everyday lives, especially in devolved areas; second, as illustrated in May 2021 on the occasion of the Senedd elections, there are growing calls for change even if it won the elections, partly due to the context and the incumbency effect.

3.1. The extent of Welsh Labour’s radicalism

Welsh Labour is regularly criticised by rival parties for not being as radical as it seems to be. It has first had to face mitigated policy results, as stressed during the 2021 campaign, especially in terms of poverty rates. Save the Children revealed in May 2021 that, even if ending child poverty was a fundamental priority of the Government of Wales, figures compiled before the Covid-19 pandemic, between 2019 and 2020, showed that 31% of children living in Wales were still living in poverty – compared to 29% in 2006-2007 (National Assembly for Wales 2008: 5) – as opposed to 30% in England and 24% in Scotland and Northern Ireland (BBC 2021b), which was emphasised by Jack Kellam, a researcher based in Cardiff, in an article written as an answer to a tweet by Marcus Barnett, a journalist8: “The harsh reality is that after two decades of Labour Government in Wales, almost a third of children live in poverty and the country remains one of the most deprived parts of the UK” (Kellam 2021). He denounced Welsh Labour’s “discursive radicalism” (Kellam 2021), in other words the fact it has created an endless stream of ambitious white papers, targets and public bodies, far more often than it has delivered “radical” transformation; or, to put it simply, Welsh Labour has been guilty of wishful thinking. The Welsh Labour government seems to have been willing to support radical reforms but only on paper, without really implementing efficient action. This has been a recurring accusation against the Welsh Government, which has multiplied consultation documents, without always putting words into action.

This “discursive radicalism” is illustrated with the aforementioned Environment (Wales) Act 2016, which committed the Welsh Government to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 80% by 2050 but did not include the obligation for the government to set intermediary targets before 2018, which was denounced by Jessica McQuade, from WWF Cymru, in October 2016: “As a consequence, we run the risk of having a government in danger of providing no detail and undertaking no substantial emission reduction during most of its term of office” (McQuade 2016).

The issue is also visible in the coalition agreement signed on 22 November 2021 with Plaid Cymru, celebrated, as mentioned above, for being “radical in content and co-operative in approach” (Welsh Government 2021: 1), and for being (as written in a tweet by Labour MP Diane Abbott on 22 November 2021) “a fantastic programme for @Mark Drakeford, the question is why can’t @UK Labour in England do the same? Maybe we should all move to Wales” (Kellam 2021). To quote another tweet by John McDonnell, Labour MP and former Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer (2010-2015), “Labour’s Mark Drakeford secures a radical programme for Wales that contains many of the policies set out in Labour’s 2019 election Manifesto, charting clear red water between Welsh Labour and the Tories” (Kellam 2021). Indeed, the agreement detailed a range of commitments for the following three years, some relatively concrete (for instance universal free school meals for primary school pupils), others hazier. The vocabulary used in the document was revealing, with the multiplication of expressions such as “to explore”, “to address issues” (Government of Wales 2021: 2), advocating the setting up of “expert groups” (Government of Wales 2021: 3) or seeking “commission independent advice to examine potential pathways to net zero by 2035” (Government of Wales 2021: 5). No real policies, with a precise timetable, had been announced in March 2022, so that it remains to be seen whether these ambitious proposals will be implemented.

This lack of action can also be explained by the obstacles and economic hurdles faced by Welsh devolved institutions, as stressed in the Co-Operation Agreement, when presenting a commitment to net zero, a target now to be reached by 2035 instead of 2050: “We support devolution of further powers and resources Wales needs to respond most effectively to reach net zero” (Government of Wales 2021: 5). The Welsh Government had to cope with the same constraints during the pandemic since the Welsh First Minister could decide on a lockdown, health being a devolved matter, but depended on the British Government for the introduction of the furlough scheme. That was the case in September 2020, when Mark Drakeford implemented a lockdown in Wales while London did the same only on 5 November. Another example is the limits to the Basic Income Pilot which will not expand, at least in the short term, into a fully-fledged Universal Basic Income in Wales due to legislative, financial, and administrative constraints, as well as the limited powers available to the First Minister. Furthermore, implementing such radical policies would create a wide gap with those introduced by Boris Johnson’s Conservative Government in London, and the Prime Minister clearly expressed his disdain for devolution and promoted “muscular unionism”9. The tensions created between the Welsh Labour and British Conservative Governments may also contribute to weakening the party’s dominant position in Wales.

3.2. Boris Johnson’s Conservative Government’s recentralisation strategy: “the unity backlash”

In a paper published shortly before the first referendum on devolution in Scotland and Wales in 1979, Welsh socialist writer Raymond Williams drew attention to two possible kinds of English reaction to the nationalist movements in those countries. The first of these was what Williams referred to as the “unity backlash”, through which a governing elite would seek to forestall and prevent other groups of people from gaining control of their own resources and working out their own futures in their own ways (Williams 1978: 189). The “unity backlash” would be carried out, Williams warned, in the name of a spurious British unity, combining emotional appeal with political rhetoric capable of masking the particular economic interests of a minority served in that name. The second possible English response Williams identified was a “why not us?” response. Williams used the rhetorical phrase “why not us?” to draw attention to the fact that many of the objectives left-wing nationalist groups in Scotland and Wales were aiming to achieve were also real material aims for socialist political movements in England: control over communal decision-making and access to resources.

Even if Raymond Williams was thinking about the impact of Margaret Thatcher’s centralising policies on Wales, his prophetic analysis can also be applied to modern Britain since Boris Johnson, after he became the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in July 2019, attempted to recentralise power in London, an issue raised in the Co-Operation Agreement: “With devolution under threat from this UK Conservative Government, we must send a clear message to Westminster that the Senedd is here to stay and decisions about Wales are made in Wales” (Government of Wales 2021: 7). Such recentralisation started during the Brexit negotiations, from which the devolved administrations were often excluded – the Sewel Convention was even breached several times over the last few years – and expanded with the voting in December 2020 of the Internal Market Act setting up a single market within the United Kingdom. The Act more precisely prevented internal barriers between the four constituent parts of the kingdom and restricted the ways that certain legislative powers of the devolved administrations can operate in practice10. The UK Government did not seek legislative consent from them, as necessitated by the Sewel Convention, even if Wales and Scotland were directly affected by the Act. It was only the second act, after the EU Withdrawal Act 2020, for which the Scottish Parliament had withheld consent since 1998, the first for the Senedd.

A further move by the UK Government has been the “levelling up” agenda, its plan to reduce inequalities between richer and poorer parts of the UK, allowing London to directly subsidise schemes in Wales and Scotland, by-passing the devolved administrations. It was announced in February 2022 that 10 projects had been selected in Wales, following bids from Welsh local authorities11 the previous year (Deans & Evans 2022). Welsh Labour ministers accused Boris Johnson’s Government of side-lining them by making spending decisions in areas under the Welsh Government’s control like transport and the environment12, as indicated by a spokesman for the Government of Wales: “This is the UK Government aggressively undermining the outcome of two referendums which backed Welsh devolutio.” (BBC 2021a). The Welsh Labour Government may hence be accountable to its voters for decisions ultimately made by the British Government.

To conclude, since the introduction of devolution in 1998, Welsh Labour has managed to assert its Welsh credentials, to promote a “Welsh brand” that is different from New Labour, first, and from the Conservative Party, next, defining “clear red water” between Cardiff and London. The different Labour First Ministers have so far defended radical measures, such as a strong commitment to the well-being of future generations and the environment, proactive economic policies in the private sector, and the Basic Income Pilot scheme. And yet, it is regularly accused of “discursive radicalism”, of being unable to turn words into concrete actions, which can be partly explained by the limited economic powers of the Senedd and the recentralisation of power in London.

During its 2022 conference in Llandudno on 12 March 2022, Welsh Labour unanimously voted in favour of increasing the size of the Senedd from 60 to between 80 and 100 members. Such a reform, with a call for a more proportional election system, had so far been a difficult topic for Welsh Labour, and with the results of the 2021 Senedd elections in mind, and Welsh Labour’s far better results in the constituency vote than the regional vote, such reluctance to reform the voting system is no surprise:

Table 2: Results of the 2021 Welsh elections.

| Constituency vote share | Constituency seats | Regional vote share | Regional seats | |

| Welsh Labour | 39.9% | 27 | 36.2% | 3 |

| Welsh Conservatives | 26.1% | 8 | 25.1% | 8 |

| Plaid Cymru | 20.3% | 5 | 20.7% | 8 |

Interestingly, this was one of the commitments made in the Co-Operation Agreement signed with Plaid Cymru, so that it may be asked whether major reforms introduced in Welsh devolution are actually victories obtained by the nationalist party rather than Welsh Labour. Indeed, the previous deep change to the devolution settlement took place in 2011, following the March referendum on full-law making powers for the Senedd, a proposal inscribed in the One-Wales agreement signed between Welsh Labour and Plaid Cymru in 2007. Is Welsh Labour, seen as a soft nationalist party, trying to be radical to attract Plaid Cymru voters? Besides, since one of the strengths of Welsh Labour since devolution has been its leaders’ credibility, with Mark Drakeford having announced he was to step down before the next Welsh elections in 2026, will the next First Minister be able to maintain Welsh Labour’s hegemony in Wales? Finally, considering its success in Wales, should it establish itself as an independent party in its own right, as asked by some participants in the conference of the Labour Party in Brighton in September 2021?