Introduction1

The fourth national elections in Wales took place on 5th May 2011, twelve years after the establishment of the National Assembly for Wales (Assembly) in 1999. During this time, there have been four fixed term elections, three major reviews of the scope of powers, and the operation of the institution, a second Government of Wales Act in 2006 and a second referendum (Stirbu and McAllister, 2011). The original new Labour proposals for devolving power to Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and London signalled a major recasting of UK constitution. Amongst the different national models within the UK’s asymmetrical constitutional landscape, Wales is arguably the most fluid settlement (McAllister, 2001, 2003). There have been significant shifts in terms of the powers exercised by the executive or government, the shape and operation of the Assembly and public support for devolution itself. This almost continual process of review and recasting has created opportunities and difficulties for the main participants in the devolution project- politicians and officials.

The territorial aspect of the UK constitution has emerged as an increasingly significant factor as the Scottish and Welsh settlements, in particular, present a higher degree of codification (since the first three devolution Acts were passed in 1998). There is also a connection between devolution and the use of the referendum device which is significant in 2011. The referendum was seen as a powerful device to legitimise constitutional debates and add legitimacy to the political institutions established. The three popularly endorsed devolution referendums in 1997 also served as powerful means of constitutional entrenchment to protect the devolved legislatures from a possible repeal from Westminster Parliament, in the absence of a constitutional guarantee similar to that found in federal systems (HL 2009).

Out of the three devolution schemes endorsed in 1997, the Welsh one has been not only the most limited (in terms of the range of powers devolved), but also the most problematic (the very marginal vote in the 1997 Referendum to establish an Assembly hardly conferred due legitimacy) and fluid of all. The Welsh ‘settlement’ since then has undergone significant changes both at operational and constitutional levels, which eventually required a further endorsement of devolution in Wales via the 2011 Referendum on primary legislative powers. The original model of devolution for Wales was constructed as a compromise and proved to be inherently flawed (see McAllister, 1998; Rawlings, 2003). It was predicated by some distinctive features: very weak designated powers for the Assembly, an immature political culture and relatively under developed civic society, low levels of enthusiasm for devolution (the original referendum recorded support of only 50.3%, with 49.7% voting against, on a low turnout of 50.1%). The new politics were also driven by a desire to create a more consensual and diverse politics, juxtaposing Wales’s politics with that historically characterising the House of Commons.

Many scholars have suggested that Wales offers one of the most interesting illustrations and extrapolations of devolution. Despite this, Wales largely remains the ‘invisible nation’ in UK and European scholarship. This review of the fourth elections in 2011 explores further the hypothesis that Scotland-which was well prepared for the re-establishment of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, with high levels of public support and enthusiasm for devolution, and a desire to be regarded as different to Westminster- has emerged with a stable model of devolution very similar to the conventional Westminster model. Wales, meanwhile, was a somewhat reluctant partner in the devolution project. Its original devolution ‘settlement’ was poorly conceived and designed, but its inherent flaws have meant a continual process of renewal and review with a system somewhat divergent from Westminster. The elections in 2011 expose further dimensions to this.

1. Background

The 2011 election was significantly different in a number of important ways: first, this election represented signalled a new political leadership class, with two new party leaders for both Labour and the Liberal Democrats) and a significant churn amongst elected Assembly Members (AMs)-23 new members were elected in 2011, over a third of the total. The fourth elections came just eight weeks after the referendum which saw overwhelming support (albeit with a small turnout) amongst those voting for the Assembly to assume primary legislative powers in its 20 devolved areas, without recourse to the Houses of Parliament. Third, the election occurred one year after the UK General Election which meant that this was the first election in Wales with ‘co-habitation’, that is governments of different political ideology and party identity in power at UK and Welsh levels. Combined this formed an influential political landscape that was to shape the campaign, approach and results of the Welsh General Election (Cole and McAllister, forthcoming).

In many respects, the referendum was anticipated to be the most significant dynamic influencing the election results. The path to a second national referendum on the mechanism by which the Assembly was able to make laws dates back to the second Government of Wales Act and indeed, the 2007 Assembly elections which had produced no overall party majority (Labour won 26 of the 60 seats, Plaid Cymru 15, the Conservatives 12, the Liberal Democrats 6 and the independents 1) (Stirbu and McAllister, 2011). The new coalition government programmes included a pledge to:

[…] proceed to a successful outcome of a referendum for full law-making powers under Part IV [of the 2006 Act] as soon as practicable, at or before the end of the Assembly term. (One Wales, 2007)

With this objective in mind, the ‘All Wales Convention’ was established by the Government with the aim of gauging public opinion on a move towards primary law making powers, as stipulated in Part IV of the Government of Wales Act 2006. There had been debate as to the value and validity of a referendum on such a technical issue. Some argued that the authority for a move had already been provided for in the original devolution referendum in 1997 (HL, 2010, Institute of Welsh Affairs submission). Yet, it is worth remembering that the 2006 Act was drafted in a rather delicate political context and public support in a national referendum was as much a political tool as a constitutional objective (McAllister and Stirbu, forthcoming).

The Convention undertook a wide consultation process, not only testing Welsh people’s views in the light of a referendum, but also seeking to raise awareness about existing constitutional arrangements in Wales. It reported to the Government on 18 November 2009 highlighting increased support for devolution (with 72% of the public favouring the present devolution scheme or greater powers), as well as the limited understanding of devolution arrangements in Wales (see All Wales Convention report, 2009, p. 7). The report also made the case for the substantial advantages presented by moving to the Part IV of the 2006 Act too.

The Convention suggested that a referendum on primary law-making powers is winnable, but with no guarantees of a ‘yes’ vote. The report was positively received in most circles, being praised by both the then First Minister, Rhodri Morgan and the Deputy First Minister, Ieuan Wyn Jones. It is significant for what follows that they focused specifically on its success in public engagement and its efforts to raise awareness about constitutional matters in Wales (WAG statement, 18 November 2009).

Subsequently, in February 2010, the Assembly unanimously passed a Referendum motion proposed by the First Minister under Part IV of the 2006 Act (NAfW RoP, 2010a). With an ensuing UK General Election and a subsequent change in government, it was not until June 2010 that the newly appointed Secretary of State for Wales, Cheryl Gillan, presented a draft referendum question for consultation (Wales Office, 2010). The Electoral Commission, as the UK’s official body for setting the standards for running elections and referenda, reported in September 2010, after public consultation, with recommendations for the wording of the referendum question and of its preamble (Electoral Commission, 2010). Draft Orders in relation to the National Assembly for Wales referendum - setting the date as 3rd of March 2011 - were laid before the Parliament by the Secretary of State for Wales on the 21st October 2010, whilst the National Assembly unanimously agreed on the Draft Referendum Order on the 9th of November 2010 (NAfW RoP, 2010b; Stirbu and McAllister, 2011).

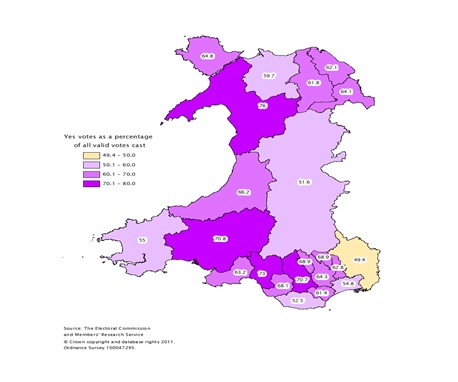

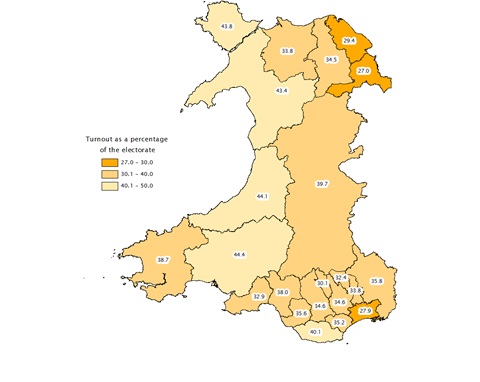

Electors voted in the referendum on 3rd March 2011 registering a convincing ‘yes’ vote. This meant the Assembly for Wales to now able to make laws on all matters in the 20 subject areas it has powers for with 517,132 of the electorate voting ‘yes’ (63.5%), and 297,380 voting ‘no’ (36.5%). This legislative shift replaced the Legislative Competence Order system introduced by the Government of Wales Act 2006, by which the National Assembly could draw legislative competence matter by matter, in the devolved subject areas, but only with Westminster’s permission. Seemingly on a technical and certainly on a complex matter, the 2011 Wales Referendum is nevertheless a significant aspect of Wales’ constitutional development process. 21 (of the 22) unitary local authority areas voted ‘Yes’ (support ranged from the highest vote of 76% in Gwynedd %) with only one area (Monmouthshire) voting No (50.6%). Equally, the turn-out varies from a low of 27% in Wrexham in north east Wales to a ‘high’ of 44% in Carmarthenshire in south west Wales- described as ‘Not brilliant but not apocalyptic’ by the First Minister, Carwyn Jones.

Local differentials in turnout in referendum, March 2011

2. The election results

In many respects, it is impossible to understand the fourth Assembly elections without locating it as part of a longitudinal sequence of elections since 1999 (see McAllister, 2003; McAllister and Cole, 2007). The fourth elections represented the first ones to a legislative parliament, following the ‘yes’ vote in the referendum held eight weeks previously (see Wyn Jones and Scully, 2012).

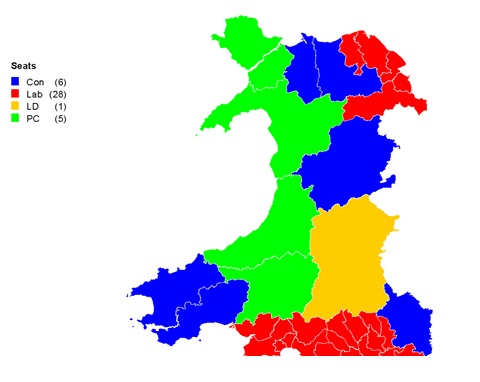

Welsh Labour had a hugely successful election gaining additional seats and polling its highest ever share of the vote in both constituency and regional ballots. It won Blaenau Gwent, Cardiff Central, Cardiff North and Llanelli while holding the two regional list seats in Mid and West Wales. Despite this, Labour failed to win a ‘working’ majority although these results did enabled Labour to eschew another coalition and to form a single-party administration.

It was also a successful election for the Welsh Conservatives, who gained the constituency seats of Aberconwy and Montgomeryshire and additional list seats in South West and North Wales. However, these gains were counteracted by two losses; first the gain at Montgomeryshire directly caused the loss of the Mid and West Wales list seat of party leader, Nick Bourne. Second, Cardiff North was lost to Labour, with Jonathan Morgan, seen by many as the leader-in-waiting, defeated. Nevertheless, the Conservatives emerged as the second largest party for the first time and continued their gradual recovery in terms of constituency representation, having obtained just one constituency seat in the first two Assembly contests, although the increase in their shares of both constituency and list votes was modest.

For Plaid, the 2011 contest represented its worst ever performance in Assembly elections, both in relation to its percentage vote and the number of AMs returned. Plaid failed to gain any of their target constituencies, lost constituency seats at Aberconwy and Llanelli, and on the South Wales Central and South West Wales lists. This was a hugely disappointing election for Plaid, especially when juxtaposed against some remarkable successes for its sister party, the SNP, in Scotland.

Not surprisingly, given plummeting opinion poll ratings following its coalition at UK level, the Welsh Liberal Democrats had a very difficult election and suffered its worst vote shares in any Assembly contest. Yet, largely due to the oddity of the AMS electoral system, the Liberal Democrats managed to retain five of its six seats. Although it lost three seats, counterbalancing gains were made on the South Wales Central, and Mid and West Wales lists. These seats were, however, narrowly won, with just 7.9% and 6.9% of the vote respectively, outcomes that might have saved face but scarcely concealed major structural and strategic questions about the future of the party in Wales.

These results also generate findings in relation to the capacity of electoral systems to generate broadly proportional outcomes through illustrating the extent to which the Welsh electoral system struggles to ameliorate the disproportional outcomes of the constituency contests. Wales uses a variant of the Additional Member System (AMS), which combines a plurality constituency ballot with regional lists to diminish disproportional results arising from those constituencies. AMS was deemed crucial to devolution because the proportional element ensured robust electoral competition and that the result was accepted as legitimate. However, the balance between the two parts of the electoral system was slanted strategically and crucially towards the majoritarian element, with two-thirds of seats selected through constituency contests. This version of AMS has struggled to compensate other parties for the advantages accrued by Labour from its constituency dominance -in 2011, Labour’s percentage of the seats exceeded its percentage of the list vote2 by 13.1%.

The 2011 elections results: constituency seats won by each party

Conclusions

Despite its self proclaimed and media nomenclature as the first ‘Welsh General Election’, this was a campaign dominated by the UK context and mainly UK issues. In reality, this election resembled more a UK mid term than a Welsh General Election. In terms of results, Labour was the unequivocal victor but, with exactly 30 seats, fell just short of winning enough Assembly seats to govern comfortably. Having said that, the minority Labour government (in the footsteps of two Labour-led coalitions) has experienced a relatively comfortable first year. It gained support from the smallest group, the Welsh Liberal Democrats, to ensure support for its first budget and instituted a very limited legislative programme at the outset. Clearly, further challenges lie ahead but for now, the co-habitation arrangement suits First Minister, Carwyn Jones, rather well as the UK coalition government advances a programme of austerity measure that have hit Wales harder than elsewhere due to the nature of its economy, employment patterns and demography.

The 2011 elections brought leadership issues of different types for each of the other three parties. Conservative leader Nick Bourne lost his regional seat as compensation for Conservative constituency gains. Kirsty Williams of the Liberal Democrats emerged from her first national election with one fewer AM but a substantial drop in support driven by backlash from her UK leader’s involvement in the coalition with the Conservatives. For Plaid Cymru’s Ieuan Wyn Jones, the loss of four seats overall was the latest disappointing result for his party and he quickly announced his plans to step down and a schedule for a new leader to be elected. Despite predictions that the referendum result would bring about a surge in support for Plaid Cymru due to its association with the devolution project and moves to strengthen the project, Plaid did poorly. This was in stark contrast to events in Scotland, where the Scottish National Party had a stellar election, winning in Labour heartlands and gaining a clear majority of seats.

Significant constraints within the model of Welsh devolution remain, especially over the capacity of the political legislature. With just 60 elected politicians, a public which is relatively unengaged, an undeveloped civil society and an immature administration, there are likely to be challenges for an ambitious far sighted government in future as well as potentially perilous scrutiny constraints. Nevertheless, it is also the case that, after twelve years, the Assembly has begun to assume the complexion of a mature political institution. It is no longer dependent on another legislature for executing laws and decisions within its own devolved remit. Clearly, this inaugurates a set of significantly changed political relationships between Wales and UK to which political co-habitation adds another layer. Over time, it is entirely realistic to expect more stable, balanced and equal inter governmental and inter parliamentary relations to emerge across the UK.